Daniel Chang’s phone wouldn’t stop lighting up.

It was the night of Aug. 6, shortly after President Trump signed an executive order banning the ubiquitous Chinese social media platform WeChat. Chang, a prominent broker at Sotheby’s International Realty, said his longtime Chinese clients rushed to swap phone numbers and email addresses, worried they would lose contact.

“A lot of people cannot fanqiang using a VPN,” he said, using the term for scaling the “Great Firewall” of China. “If you’ve lost WeChat, you’ve lost everything.”

For all its problems, the U.S. has historically been considered one of the safest major markets for business, with a robust legal system and a government that’s stayed out of the way of private enterprise. Those same factors made it a top global destination for real estate investors. But the Trump administration’s unprecedented crackdown on WeChat coupled with its recent efforts to force a sale of TikTok could have a chilling effect across several industries, according to experts.

“This is an administration that believes in what economists call ‘managed trade.’ That is, instead of letting the market decide things, we should regulate,” said Bill Reinsch, a trade expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “The message is, “we want you to do things our way and we want you to promise to do things our way.’”

The moves could further dampen Chinese interest in U.S. real estate, notably on two crucial fronts: wealthy individuals who use WeChat to find and invest in U.S. residential property and Chinese institutional investors and lenders who have pumped billions of dollars of debt and equity into the local market.

If you’ve lost WeChat, you’ve lost everything.

“Foreign investors are used to thinking about political risks when operating in developing countries with weak legal institutions and rule of law,” Brookings Institution fellow Geoffrey Gertz wrote on Aug. 7. The TikTok and WeChat bans, Gertz wrote, suggest that “political risk should be a core concern for any global company attempting to operate across the U.S.-China divide.”

Key money

The White House says TikTok and WeChat – which are used by an estimated 2 billion people worldwide – are national security threats. After Trump signed executive orders banning the apps, Peter Navarro, the White House director of trade policy said the apps had put Americans in “the crosshairs of an Orwellian regime.”

“It’s 10 p.m.,” Navarro quipped. “Does the Chinese Community Party know where your children are at?”

Trump, ever the real estate operative, has also characterized TikTok in industry terms and argued the U.S. government should get a cut of sale proceeds. “It’s a bit like the landlord-tenant,” he said on Aug. 3. “Without a lease, the tenant has nothing. So they pay what’s called key money, or they pay something.” (New York real estate observers would have noted the irony of this phrasing, given that TikTok signed one of the city’s largest new office leases in May at the Durst Organization’s Times Square tower.)

Trade experts warned that the president’s actions suggest a U.S. hostile to international business. The bans, Eurasia Group’s Paul Triolo told CNN, represent an “unprecedented intervention by the U.S. government in the consumer technology sector.”

Does the Chinese Community Party know where your children are at?

TikTok slammed Trump’s executive order as setting a “dangerous precedent” and undermining “global businesses’ trust in the United States ” (On Aug. 27, TikTok CEO Kevin Mayer resigned, reasoning that “the role that I signed up for — including running TikTok globally — will look very different as a result of the U.S. administration’s action to push for a selloff of the U.S. business.”)

Nobody knows

The U.S.-China trade war has already taken a big toll on commercial real estate.

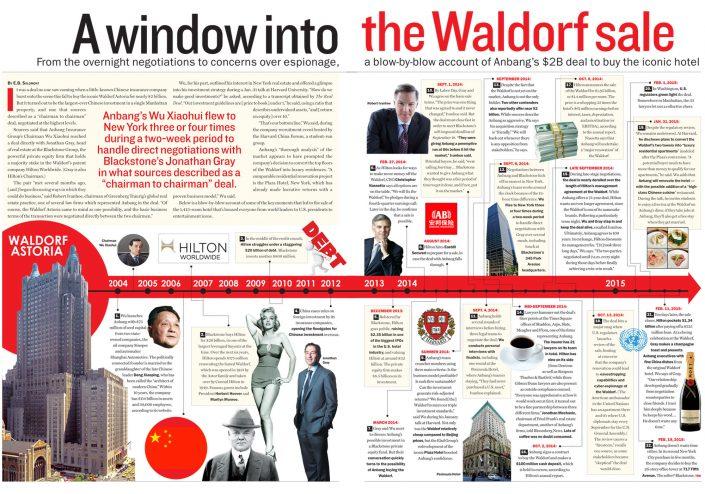

Chinese investment in U.S. real estate hit a high in 2016, when investors poured $19.5 billion into commercial property deals, according to Real Capital Analytics. But Beijing’s strict capital controls, enacted late that year, put an end to record deals that included Anbang Insurance Group’s $1.95 billion purchase of the Waldorf-Astoria in 2014, HNA Group’s $2.2 billion buy of 245 Park Avenue and Fosun International’s $725 million purchase of 28 Liberty in 2013.

Last year, Chinese investment in U.S. real estate plummeted to $827 million and Chinese firms are now racing to sell their U.S. assets under pressure from Beijing. In 2019, Chinese investors sold more than $20 billion worth of real estate, according to Real Capital Analytics.

The under-fire Anbang, for example, has put its portfolio of luxury hotels on the market, while HNA is unwinding assets acquired during a $50 billion spending spree. Last month, Dalian Wanda Group agreed to sell its 90 percent stake in Chicago’s Vista Tower in Chicago for $270 million.

Observers said the Trump administration is looking to hurt China where it is most vulnerable. The president proposed new sanctions on Hong Kong in July, after China moved to revoke the city’s special status, which had allowed it to function as an international banking hub.

The forced sale of TikTok — could start impacting that flow of capital.

“There were holes in the system, where Chinese families and even companies could move money to Hong Kong and set up Hong Kong entities that they could invest real estate through,” said one Chinese lender.

The Hong Kong conduit is now in question, and the lender said no one knows how far the U.S. government will go to hamper Chinese and Hong Kong financial institutions, including banks. “You could wake up and they could say you have to stop doing new business as a bank,” the lender said.

Alex Foshay, head of international capital markets at Newmark Knight Frank, said Chinese bank lending could be the “other shoe that has yet to drop,” said In 2019, mainland Chinese banks loaned $4.2 billion on commercial real estate deals including $2.3 billion in New York City, NKF data show. Year to date, banks have loaned just $1.73 billion, primarily on New York deals.

“Chinese lending has continued to be very aggressive in recent years,” Foshay said. “The current trade war — and more specifically, the forced sale of TikTok — could start impacting that flow of capital.”

The lender source disputed that scenario, pointing out that Chinese banks in the U.S. are funded locally. Beijing also likes the optics of Chinese banks doing business around the world.

“It’s a marketing statement to say, ‘We have a global financial powerhouse,’” the lender said.

Message not delivered

The WeChat ban is not just a political headache. It’s also a serious logistical and communications one.

“WeChat is almost like an addiction, it’s a necessity of life for anyone from China,” said the Chinese lender, who noted that even banks rely on the social network as an important back channel.

“Compared to all the other attacks on China, it’s on the mechanical side of communication,” said RCA’s Jim Costello.

For that reason, the ban has big implications beyond real estate. “It would practically shut down communication between the U.S. and China,” Graham Webster, a China expert at think tank New America, told Bloomberg.

In an Aug. 11 call with White House officials, more than a dozen major U.S. corporations including Apple, Goldman Sachs and Ford, said the ban would undermine their competitiveness. “For those who don’t live in China, they don’t understand how vast the implications are if American companies aren’t allowed to use it,” Craig Allen, president of the U.S.-China Business Council, told the Wall Street Journal.

For many would-be property investors, the uncertainty of whether WeChat really will be banned is harrowing. Reinsch predicted many will sit on the sidelines until after the November presidential election. But Costello pointed out that the ban could also hurt investors who already own assets in the U.S.

“Managing those assets and communicating with service providers, customers, and investment partners all happens on WeChat,” he said.

According to Sotheby’s Chang, many clients are testing other apps — iMessage, QQ, AliPay, WhatsApp, Line and Telegram.

Chang said he’s concerned about record retention, since he stores some proprietary information on WeChat. But the thing he fears most is the loss of market intelligence. For instance, although institutional investors have already pulled back, parents of Chinese college students who don’t want them living in dorms during Covid are still interested in the residential market.

“I see what the Chinese people are posting, or not posting,” Chang said. “That’s what I’ll miss.”

—Kevin Sun contributed reporting.