When the owners of Industry City embarked on the seven-month rezoning process, they lacked what developers treasure most: certainty.

Those who enter New York City’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, or Ulurp, typically do so confident that their project will ultimately be approved: They have received the blessing of the mayor and at least a positive sign from the local City Council member, the gatekeeper for land-use decisions.

But Industry City’s owners, promising to invest $1 billion if allowed to rezone the 35-acre campus, filed an application without any support from Sunset Park Council member Carlos Menchaca. In fact, he had twice forced the owners to postpone filing, saying the community needed more time for analysis.

But opposition only increased — not just to the plan, but to the process itself.

“Ulurp is insufficient for evaluating displacement, gentrification, and the effects of climate change,” Menchaca wrote in March 2019 to the development team. “This is because Ulurp operates like a negotiation, not a fact-finding mission. For the negotiation to succeed, the community must come ready with its vision and desired outcomes in place.”

The development team —a partnership between Jamestown Properties, Belvedere Capital and Angelo, Gordon & Co. — eventually moved forward despite Menchaca’s warnings. Talks with the Council member broke down more than halfway through the review process and last week, unable to overcome his opposition, the campus owners withdrew their application.

The saga underscores often-maligned aspects of the city’s land use review process. Many in the real estate industry have long criticized the City Council’s tradition of voting along with the local member’s wishes, known as member deference. Elected officials and community groups have also blasted Ulurp in recent years for its failure to consider the racial and socioeconomic impacts of zoning changes.

To be sure, Ulurp’s limitations are secondary to the growing animosity toward development itself, but the combination of factors could deter builders from risking Ulurp entirely — a dangerous prospect at a time when the city is in dire need of investment and jobs.

“There’s no way to sugarcoat it,” said Paimaan Lodhi, a senior vice president at the Real Estate Board of New York, reflecting on Industry City’s defeat. “This is discouraging to the development community and anyone who wants to invest in New York City.”

Raising the bar, falling flat

The opposition to Industry City has often been compared to that faced by Amazon when it proposed building a headquarters in Long Island City two years ago. Critics of both projects argued that they would not benefit existing local residents and indeed would displace them by accelerating gentrification.

Supporters of urban growth are alarmed.

“The fear is we’re going to succumb to short-term thinking and politics,” said Mitch Korbey, chairman of Herrick’s land use and zoning group and former director of Brooklyn’s Department of City Planning. “This is not about process or a failure of urban planning. We need to think beyond the immediate couple blocks. We need to think more holistically.”

Lodhi said the withdrawal of Industry City’s application could have a chilling effect on private rezoning applications. He said the rezoning, which would have allowed for more retail, commercial and academic space on the 16-building campus, “checked a whole lot of boxes” when it came to potential long-term benefits for the community. The developers had also modified the plan in response to local feedback, yet still failed.

“What makes the Industry City example of such concern is that this was a developer that did speak to the community at some length, over many years, over many, many meetings,” said Carl Weisbrod, former City Planning Commission chairman who now works as a real estate consultant with HR&A Advisors, which lobbied on behalf of Industry City. “I don’t think there’s something inherently wrong with the Ulurp process. It’s just gotten a lot more difficult to go through the public review process.”

It’s hard to say the [Ulurp] process works when we had this outcome on a project of such citywide importance

Industry City CEO Andrew Kimball believes his team “raised the bar” for future developers with its outreach and concessions. The team agreed to eliminate hotels and dormitories from the plan. A community benefits agreement with an independent coalition of local groups would have barred the leasing of the last 200,000 square feet of retail space or the last 500,000 square feet of new construction space until at least 11,000 people were employed at the project, including a certain percentage from Southwest Brooklyn.

“I’d like to think we carved a new path here, in terms of turning the Ulurp process upside down, where decisions are often made in back rooms at the 11th hour,” Kimball said. “We’ve been very transparent about what we’re putting on the table.”

Read more

Kimball was brought onto the project in 2013, after spending eight years as CEO of the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corp. He has repeatedly pointed to his role there — where he worked with the Bloomberg administration to transform the struggling ship-building facility into a vibrant mixed-use campus — as a model for how the Industry City team engaged the Sunset Park community.

But a key difference from the Navy Yard is that Industry City is privately owned. Moreover, the political dynamic has turned against development since the Navy Yard’s celebrated turnaround. Neither Mayor Bill de Blasio nor City Council Speaker Corey Johnson would publicly support the rezoning.

“It’s hard to say the [Ulurp] process works when we had this outcome on a project of such citywide importance,” Kimball said. “It’s hard to say the process works when we have not been successful in engaging the most important citywide leaders on the substance and importance of the project.”

Calls for reform

Though three City Council members came out in favor of the rezoning, the chamber as a whole appeared poised to back Menchaca. This wasn’t just a case of member deference, however. Nearly a dozen elected officials who represent Brooklyn — including four members of Congress — also spoke out against the rezoning, saying it would “supercharge the displacement and gentrification of the neighborhood.”

Community groups and elected officials also feared that pledges by the development team were not enforceable. For instance, the developers said they intended to build a vocational high school on the campus, but could no guarantee it because the city’s Department of Education had not yet granted the necessary approvals. Groups also called the development team’s projection of 20,000 jobs misleading, as the sum included 8,000 existing jobs and thousands created indirectly offsite.

Cesar Zuñiga, who chairs Brooklyn Community Board 7, said the rise and fall of the Industry City application highlights the superficial role community boards play in the land-use process. Developers regard listening to the concerns of the residents as a box to check off and then dismiss, he said.

“It just makes a mockery [of the idea] that the community matters and the community’s voice is respected,” he said. His board split on Industry City’s application, disapproving certain aspects and failing to reach a consensus on others. As with any Ulurp application, the community board’s vote was a recommendation, not binding, as was the borough president’s review after it.

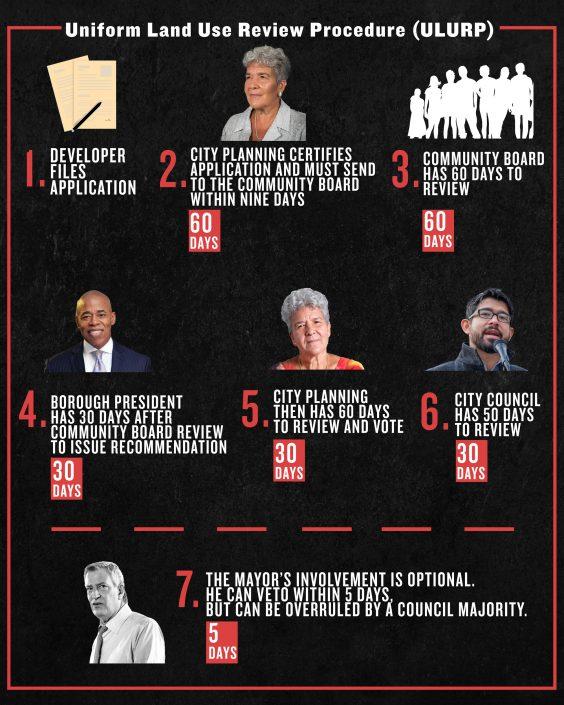

Ironically, Ulurp was established in 1975 in part so community boards could weigh in on land-use changes. In the 1989 City Charter revision, the City Council and City Planning Commission were granted more authority over such decisions as well, with the elimination of the Board of Estimate — a governing body that was declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Ulurp has barely changed since. Last year, voters approved two small revisions, granting community boards an extra 15 to 30 days to review applications filed in June and July, and requiring City Planning to provide boards with detailed information on applications in the pre-certification phase.

Zuñiga said the city needs to provide more resources for board members and residents to meaningfully engage in land-use debates — and to level the playing field as they negotiate with developers armed with experts and attorneys.

Community members also have a relatively short window to secure major changes to a rezoning proposal, noted Tom Angotti, professor emeritus at Hunter College’s Urban Policy and Planning department. Before Ulurp starts, the developer must hold a public meeting, laying out the potential scope of the project. Then the developer drafts an environmental impact study and another hearing is held.

Once the City Planning Commission certifies the application, starting the seven-month Ulurp schedule, certain changes can’t be made to the proposal without having to redo the environmental impact study — a lengthy and expensive proposition.

“The only thing that can change during that process … is if the city or developer reduces the scope of the project so that it has less of an impact,” Angotti said. “It makes it difficult to do any real planning during the Ulurp process.”

A spokesperson for City Planning said the agency encourages Ulurp applicants to discuss their potential project long before the review process officially begins. The spokesperson noted that most proposals that reach the City Council are ultimately approved.

A recent legal challenge in northern Manhattan called for a major overhaul of Ulurp. In a lawsuit, a community coalition persuaded a state judge that the city was obliged to analyze the effects of a proposed Inwood rezoning on the racial makeup of an area. An appellate court disagreed but the coalition, Manhattan is Not for Sale, is seeking permission to appeal.

Last year, Public Advocate Jumaane Williams proposed legislation to require a racial impact study as part of Ulurp. He renewed that call in opposing Industry City.

Industry City also caught the attention of the Citizens Budget Commission. The group, which normally pays little attention to land use decisions, announced in August that it would launch an “in-depth study” of the city’s process and policies. President Andrew Rein said the group decided to take a close look because the process is “bogged down and not producing the results that benefit New Yorkers.”

There are other signs that change is needed, Angotti said, noting that the de Blasio administration set out to complete 15 neighborhood rezonings and in seven years has only completed six.

“I think it is telling us observers that something is not working,” he said. “And it is not enough just to say there is an environmental review that is just going to look at impacts, or that there are going to be side deals to make the communities happy. There has to be a continuous engagement.”