Claire Smith hesitates to call herself a landlord. At least, she said, not a “corporate landlord.”

Growing up in Brooklyn, she had heard East New York was one of those neighborhoods you avoid. But upon working there, she grew to appreciate the tight-knit community and later purchased a two-family home on a $36,000 salary through a now-defunct city program. The $1,300 a month from her rental unit made it possible.

Within a few years, however, Smith was thrust into foreclosure after her tenant lost a city subsidy and could no longer pay rent. Desperate to save her home, she won an eviction in Housing Court — where a judge once mistook Smith, who is Black, for a tenant.

Over the years, new tenants moved in, but Smith is still fighting off the same foreclosure effort, by HSBC. Her odds got worse when her tenants lost their jobs in the pandemic. Although Smith and her tenants applied for rental assistance through an emergency state program set up for exactly these situations, the agency doling out the funds has not responded, she said.

Other potential reprieves are unavailable to Smith. Her mortgage is federally backed, making it eligible for deferral of payments, but HSBC is not participating in that program.

Smith has not heard any update on her case since the courts shut down in late March, after which Gov. Andrew Cuomo suspended foreclosures. She does get daily calls from house-flippers and private equity firms — “vultures,” she calls them — aware of her precarious status. Unpaid mortgage bills are accumulating with interest, she said.

“I’m just waiting for the foreclosure to be executed, and I have no idea where I stand in this process,” said Smith. “I want to stay on my mortgage — I’m invested in the community, I’m not a flipper. But it doesn’t matter, because I’m just a file.”

Since April, nearly 1,400 foreclosure cases have been filed in New York City — mostly on homes with one to four units — in anticipation of the governor’s moratorium ending. Holes in the state’s protections leave some homeowners vulnerable, and new court protocols can have the effect of excluding them from foreclosure proceedings.

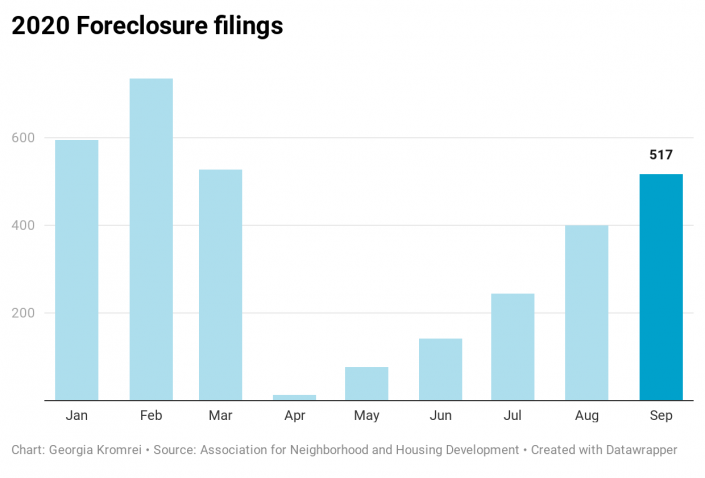

An analysis by the Association for Neighborhood Housing and Development, a nonprofit that advocates for racial and economic justice in housing policy, found 517 foreclosure cases were filed in September, the most since March, and have increased for five consecutive months.

The greatest concentrations were in the usual epicenters of housing distress: east Brooklyn, southeast Queens and the Bronx. In Brooklyn, 135 cases have been filed since April in Ocean Hill, 89 in Canarsie and 79 in East Flatbush. Saint Albans, Queens, has had 64 and Pelham Gardens, Bronx, has had 43.

When the coronavirus swept through New York in the spring, the courts were closed altogether, which immediately stopped foreclosure filings. A court order barred any new foreclosure action until after June 20, but an executive order allowed cases to be filed if the borrower was not eligible for unemployment benefits or faced no financial hardship from Covid-19.

Counselors who work with homeowners behind on payments blame that exception for the rise in foreclosure filings.

Some homeowners who were in default in March but may have been on the path toward becoming current were hit with a government-mandated shutdown — and were also shut out of relief because their troubles preceded Covid.

Yangchen Chadotsang, of Chhaya Community Development Corporation

Yangchen Chadotsang, a counselor at Chhaya Community Development Corporation, a nonprofit that does foreclosure prevention work, said community organizers were shocked at lenders’ “lack of understanding” with borrowers who did not fit neatly into the forbearance program requirements.

“It doesn’t make sense,” she said. “If someone was behind on their mortgage, and Covid made it even worse, how could they not provide the forbearance to them?”

Chhaya is working to reach Queens borrowers facing foreclosure, especially those in the Southeast Asian community. The language barrier has made it more difficult for immigrant communities to keep up with rapidly changing policies.

The nonprofit translates materials on options for struggling borrowers, but must compete with the house-flippers, deed fraudsters and attorneys who pitch their services to the desperate, and charge them exorbitantly.

The inundation of deceptive offers can make it difficult for foreclosure prevention counselors to reach clients because they are sometimes confused for fraudsters. That skepticism is warranted, according to Chadotsang.

“It’s very important for homeowners to be cautious — they get a number of letters on a daily basis,” she said.

The public filing initiates a flurry of offers to purchase the home in cash, to modify the loan or to provide costly legal services.

A 2018 report found that foreclosures fuel house-flipping — purchasing a house and rapidly selling it. The authors argued the practice erodes affordability by inflating home prices, especially in east Brooklyn, southeast Queens and the Bronx.

Jacob Inwald, Legal Services

Many of the recent foreclosure filings were “teed up” before the pandemic, said Jacob Inwald, director of foreclosure prevention at Legal Services. Cases involving borrowers who in March were already headed for foreclosure are now working their way through the court system.

“Until fairly recently there couldn’t have been any filings because the state court system wasn’t accepting them,” Inwald said. “Now filings are gradually resuming, although the pace is picking up.”

The courts require a conference be scheduled for parties in foreclosure cases before any motions. But legal providers say homeowners often don’t receive notice and go unrepresented at the conferences. Some courts delegate to the foreclosing party the responsibility of notifying defendants. In a July letter, Legal Services criticized the practice and pointed out that not all defendants have internet access to attend remote conferences.

As the courts get back into gear, Inwald fears an influx of foreclosures will erode minorities’ home equity — which they have built at rates far behind whites.

“Foreclosures disproportionately impact communities of color — you can go into any foreclosure court, look around you and see who the defendants are,” said Inwald. “We anticipate the next wave will be no different.”