When the de Blasio administration announced the Open Restaurants program over the summer, Roni Mazumdar, the owner of Indian eatery Rahi, thought he was out of luck. A fire hydrant in front of his West Village restaurant blocked him from setting up chairs and tables as required by the program at the time.

Luckily, there was a vacant space next door and with the owner’s permission, Mazumdar was able to open for business in front of his neighbor’s building.

Then, the city’s inspectors came knocking. In less than two weeks in September, Rahi got three notices, according to records shared with The Real Deal. At the time, the move was prohibited by the city, though that didn’t stop many restaurateurs from doing the same thing (and hospitality trade groups supported the move).

But then, the rules changed: On Sept. 25, the de Blasio administration amended its guidance for the outdoor dining program, allowing restaurants to set up in front of adjacent properties with permission from the owner. The announcement came after weeks of back and forth between Mazumdar and the city, and just two days after he received his third notice from the city.

Mazumdar’s experience is not unique; as the city has dealt with forces beyond its control — weather, a pandemic whose severity has waxed and waned multiple times in a year — it has changed the rules and regulations of its indoor and outdoor dining programs multiple times, often with little notice to restaurateurs who must adapt quickly to those changes.

It hasn’t been easy.

“I constantly feel like I’m jumping through hoops that we don’t need to jump through if there was clarity,” Mazumdar said. “I feel that the city officials are coming up with a lot of these plans that are heavily disconnected from reality and what’s happening on the ground. And that’s what’s causing this damage.”

Read more

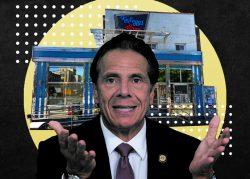

The most recent indoor dining ban, for example, was announced by Gov. Andrew Cuomo on Dec. 11, after several days of hedging over whether or not restaurants would be forced to shut down. It went into effect on Dec. 14, giving restaurant owners just three days over a weekend to adapt.

With that change came a new directive from the State Liquor Authority, stating that customers “may not enter the inside of the establishment for any reason,” including using the restroom. After pushback, that guidance was retracted a mere 24 hours later.

And when a winter storm hit the city several days later, outdoor dining was put on a temporary pause. Many restaurateurs, including Mazumdar, were confused about whether their structures had to be dismantled to make room for snow plows or could remain in place. (The city’s official guidance called for restaurants to “remove or secure” curbside eateries in the event of an accumulation of a certain amount of snow.)

“There’s a lot of consternation,” said William Mack, a partner at Davidoff Hutcher and Citron, which works with restaurants responding to such changes. “Nobody in the restaurant business right now is trying to get away with anything.”

One of Mack’s clients was hit with a major fine after setting up an outdoor dining kiosk in a bus lane minutes before it was permitted to at 7 p.m.

“That’s not the government working with businesses to try and help them survive,” Mack said. “You have to enforce these regulations with some semblance of reasonableness.”

For restaurants, which often have thin margins and few staffers — especially during the pandemic — evolving as the regulations change can be next to impossible.

“My question is: How many resources do you think we have?” Mazumdar said.

The fact that the changes often come with little notice doesn’t help. When Gov. Andrew Cuomo shut down indoor dining, the announcement came on a Friday during a press conference. Restaurants were to make adjustments by the following Monday.

Those changes affected outdoor dining as well, including mandating that any structures had two open sides to allow for airflow in order to be considered outdoor dining. Structures can cost thousands of dollars to set up and maintain the first place.

The city’s Department of Transportation, which oversees enforcement of the outdoor dining program, has made efforts to help restaurants as the seasons changed, distributing sandbags, barriers and reflective strips for use on curbside eateries. But for some restaurateurs, it’s not enough.

15 East at Tocqueville (Photo via Alex Karasev)

Marco Moreira, the owner of 15 East @ Tocqueville near Union Square, said he’s spent six figures on his outdoor dining set-up, including on heaters that align with the city’s current standards.

“I don’t think that the people in charge actually even understand what they’re doing for restaurants,” Moreira said.