It’s virtually a done deal.

A public company whose founder has created real-world property firms is poised to sign the biggest-ever deal for land that doesn’t exist in the material world. The transaction, in a virtual reality platform called Decentraland, is expected to far surpass the $850,000 that a buyer paid in July for a parcel in The Sandbox, according to a person familiar with the deal. The company is even mulling plans to spin off the purchase as a REIT — and possibly list it on the NASDAQ.

It’s a coming-out event for the Metaverse, where gamers and cryptocurrency speculators have long gathered to play and trade digital collectibles. A virtual real estate industry is being born, and traditional property developers are racing to cash in.

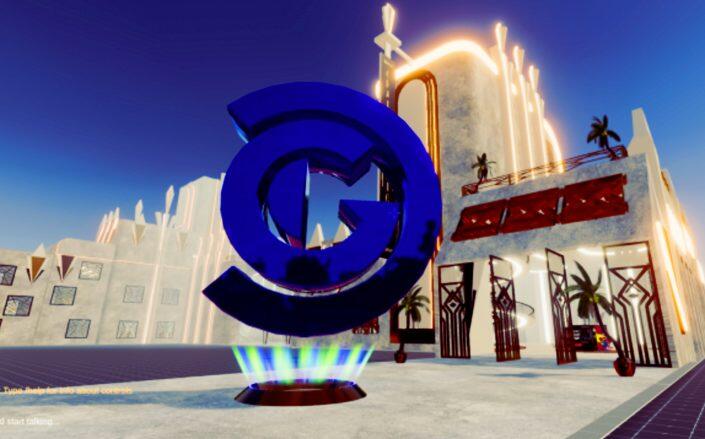

Decentraland’s Trade Center

Investors in virtual property are “hugely diversified and very deep-pocketed,” said Ryan Freedman, general partner at the venture capital firm Alpaca VC. “What they’re going to do with it, I think, is currently in the ideation phase.”

The Metaverse concept dates back at least three decades. Novels including 1992’s “Snow Crash,” whose author, Neal Stephenson, is credited with inventing the term, and films such as “The Matrix,” in 1999, stoked interest in virtual worlds. The concept matured in the past five years with the rise of popular games like Fortnite and Roblox — and especially the explosion of cryptocurrency, the backbone of the Metaverse’s system of value creation.

The global pandemic also stoked interest in the Metaverse, as locked-down populations searched for alternate realities. One result: The recent mania surrounding non-fungible tokens, or NFTs — unique digital assets secured by blockchain technology — which individuals trade in the Metaverse.

The Decentraland buyer is a public company whose founder played a role in forming some of North America’s biggest REITs, the person familiar with the deal said, declining to name it. The buyer may repackage the assets as a REIT and then return to the market to raise capital, the person said. An agreement may be reached within the next few weeks.

Granted, today’s dominant metaverse may wind up being the next Netscape — a flop. And cryptocurrencies are notoriously volatile, with prices that often soar or slump 25 percent, and sometimes much more, in a single day. Still, long-term speculators typically have been winners: Ether, the native token of the Ethereum blockchain, on which much of the Metaverse is built, climbed to a record $4,362.35 in May from just 52 cents in 2015.

The Metaverse today, like the early Internet, is a fragmented field of discrete metaverses, each a finite landscape with its own coding language and basic units of size and value. Two dominate: Decentraland, which is oriented around arts, entertainment and ecommerce, and the Sandbox, which focuses primarily on gaming.

Investors in virtual property are “hugely diversified and very deep-pocketed,”

On a computer screen, maps of these metaverses look like a game of Tetris: perfect squares arranged in small and large, sometimes irregular, formations. At the ground level, one navigates it like one would a normal two-dimensional video game world. You can walk or run around, drop into homes, arenas and other buildings, or teleport to another location through a combination of keystrokes.

Decentraland

“The next generation is going to spend much more time in the virtual world than us, and many of them may not be able to access physical property anymore, due to the rising prices, and the decreasing availability,” Sebastien Borget, co-founder and COO of The Sandbox, said. “Expanding into property in the virtual world, where they could sell unique locations and do large-scale development that go beyond the laws of physics — it’s an interesting value proposition.”

Eventually, the many coders, architects and graphic designers working on the Metaverse will have created a critical mass of residential and commercial buildings, as well as entertainment venues — a three-dimensional experience accessible to anyone. A digital real estate agent based in Memphis will be able to walk down a virtual street with a prospective buyer from Bangalore, dip into various virtual properties, and arrange a mortgage. The agent might even catch a post-deal hangout at a virtual concert down the street.

Digital land grab

Private individuals, corporations and, increasingly, real estate speculators around the world are engaged in a digital land grab. Because land in these metaverses is finite, and because speculative interest is building exponentially as its potential use cases multiply, prices are surging.

The Sandbox had its largest virtual land sale in July, when a buyer paid 3.2 million SAND, or the equivalent of about $850,000 at the time, for a 24-by-24-parcel (each one-by-one plot in The Sandbox is 96 meters by 96 meters in length and 128 meters in height). Less than two months later, the property is worth $2 million, thanks to SAND’s run-up in value in the crypto market.

Pricing is particularly aggressive for the larger plots, or estates, that companies like Atari or the media franchise “The Walking Dead” have staked out. And yes, “location, location, location” holds true in the virtual world: Plots with proximity to major thoroughfares, land owned by dominant brands, or already bustling developments are fetching higher prices.

Your blockquote here…

It’s not just gaming and media companies. Retailers and commercial property developers, many of them based in Asia, have also entered the scene.

For now, you can still buy some digital property cheaply. In Decentraland, a one-by-one parcel — the smallest unit and the real world equivalent of roughly 16 by 16 meters — can cost as little as a few thousand dollars. The low prices won’t last long, Metaverse investors and creators say. Once one or a few metaverses achieve a critical mass of users, they will have cornered the market.

“To develop virtual real estate is expensive and takes a certain skill set,” Alpaca’s Freedman said. “Once you have a lot of people doing that in one metaverse, you have density, you have liquidity, you have supply. And to create that inorganically in a new place is very difficult.”

Commercial use cases

While some commercial use cases may be years from being fully realized, some early digital property development mirrors real world counterparts. A casino, for example, is already up and running in Decentraland.

Decentraland’s casino

Elsewhere in the Metaverse, retail brands are looking to build virtual showrooms in a bid to augment the consumer experience — a commercial real estate catch phrase as legacy brick-and-mortar retail brands seek to stave off ecommerce — and capture the attention of a younger audience.

TJ Kawamura, head of product for real estate at Republic Realm, a Metaverse investment platform and the largest landholder in The Sandbox, said he fields calls daily about how to build retail experiences in the Metaverse. Some are affiliated with ecommerce brands, and many are dedicated real estate investors.

“A lot of retailers don’t know how to reach the younger generation, who are spending all their time on their phones,” he said. “The Metaverse provides a more experiential way for them to tap into that submarket.”

Kawamura, who has a background in traditional real estate, said the Metaverse is fertile ground for retail landlords, too. Digital malls, where ecommerce brands may lease and build out dedicated spaces, are under construction. “The traditional landlords may move a little more slowly, but they’re definitely coming,” he said.

Some companies have already built virtual offices in Decentraland where workers can interact, and others will follow, said Noah Swain, a physical-turned-digital real estate agent who now heads up NFT Property Group, a virtual real estate brokerage.

“There’s so many ways you can monetize these properties,” Swain said. “Some of them are similar to the ways you would monetize traditional real estate, like leasing. And then there are some things you could do that you wouldn’t be able to do with conventional real estate, like new gaming concepts. The possibilities are limitless.”

The future

The Metaverse landscape five years from now may look significantly different. In June, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said the company will build out its own virtual world and aim to become a full-fledged Metaverse firm. The arrival of Facebook and other tech behemoths will shake up digital real estate, which is now essentially democratized and collaborative.

Alpaca’s Freedman is skeptical that any of the major legacy real estate developers will come to be trendsetters, or even significant players, in the Metaverse.

“This isn’t going to be SL Green building office space and leasing floors here. It’s not going to work like that. This is companies and brands that want to drive experience. This is another touchpoint between a brand and its consumers.”

Jesse Alton, an advocate for Open Metaverse, a group working to establish open source standards, worries that the arbitrary scarcity of digital land — metaverses don’t have to be finite, he said — and the steep run-up in digital real estate values will alienate individual participants and ultimately stunt the Metaverse’s growth.

“It’s really hard for the general public to get involved, and it’s not going to get easier,” Alton said.

The larger risk is that dominant commercial enterprises in the real world like Facebook will corner the market with a “walled garden” — a closed, proprietary metaverse that defies the public and collaborative endeavour that enriches the technology’s promise, according to Alton.

“We don’t want to bend the knee and join the Facebook cult,” Alton said. “We want to create something of our own, that’s open, that anyone can be part of.”