Two weeks before the New York City Council was to vote on an upzoning to let Tom Li turn a Prospect Heights McDonald’s into an apartment complex, the developer was not feeling too optimistic.

Anti-development fervor stretched across the city. The local senator, Jabari Brisport, had fingered Li’s project and its ilk as responsible for “bleeding out Black people from the community.” The community board had rejected it, as did Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, despite having campaigned for mayor on a pro-development platform.

“We thought that it was over,” said Li.

So it came as a surprise to Li and his team at Brooklyn-based Vanderbilt Atlantic Holdings when the pivotal player in the approval process, City Council member Laurie Cumbo, signed off in September on their plan for 840 Atlantic Avenue. A deal came together at the 11th hour to lower the density and deepen the affordability.

Vanderbilt Atlantic Holdings’ success was hardly assured. Rezoning proposals in New York City turn on the whims of a single Council member and on public opinion that’s shaped more by emotion than by logic.

In Crown Heights, Ian Bruce Eichner’s plan to build two residential towers was just derailed by supporters of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, which his project would shadow for part of each day. And at Manhattan’s South Seaport, Howard Hughes Corporation has been fighting Nimbyists who prefer a parking lot to a mixed-use development that would endow a museum and add affordable housing.

Every rezoning in New York is different. And the developer of 840 Atlantic Avenue still needs to overcome a lawsuit brought by McDonald’s. Still, Vanderbilt Atlantic Holdings’ experience is a case study for how a developer can push a rezoning across the finish line.

It also represents a subtle shift in how Council members view development in a housing-starved city where well-off residents flex political muscle to shut down any prospect of new apartments — joined by far-left activists in a potent if accidental alliance.

“It shows that it is becoming more possible in the city to rezone wealthy neighborhoods,” said Will Thomas, executive director of Open New York, a pro-housing nonprofit.

Milkshakes out; oat milk lattes in

The intersection of Atlantic and Vanderbilt avenues would make any developer drool.

It sits across from the Pacific Park (formerly Atlantic Yards) megadevelopment, one block from the A and C subway lines and a 10-minute walk from the Atlantic Terminal transit hub and Barclays Center. The adjacent strip of Vanderbilt Avenue is the city’s newest Restaurant Row.

Prospect Heights is like Lower Manhattan and Williamsburg with wider streets and fewer finance bros. The once quiet, tree-lined enclave of elegant brownstones has become a neighborhood where millennials can get an oat milk latte without having to fight an influencer for it.

Vanderbilt Atlantic Holdings saw the potential of the corner lot in 2017, paying $7 million to acquire a 99-year lease and become McDonald’s landlord. The deal at 840 Atlantic Avenue — a bargain in retrospect — made little noise at the time.

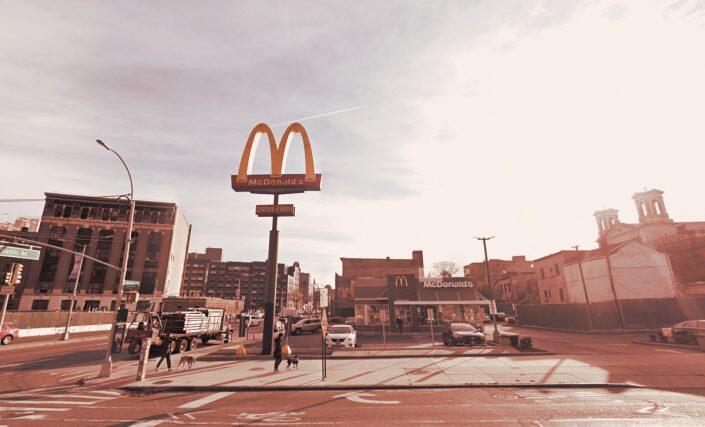

The McDonald’s at 840 Atlantic Avenue (Google Maps)

The development team consisted of real estate unknowns Li and Sam Rottenberg, along with passive investor Simon Dushinsky, a Hasidic developer behind Williamsburg’s high-rise boom. (Dushinsky, head of Rabsky Group, is notoriously press shy; no pictures or media interviews of him appear to exist online.)

Vanderbilt Atlantic Holdings’ plans to redevelop the site were first revealed by journalist Norman Oder in 2019. A year later, the outfit pitched to Community Board 8 an 18-story, 316-unit building with 95 affordable apartments and commercial and community space to replace the McDonald’s, a parking lot, two vacant lots and three three-story residential buildings. It tapped Industry City-based IMC Architecture to design the project and hired the white-shoe law firm Slater & Beckerman (now Hirschen Singer & Epstein) as its lobbyist.

But there was a problem: The plans did not conform with Community Board 8’s own rezoning plan.

The board’s M-Crown plan — which city planners did not endorse — would upzone some Crown Heights and Prospect Heights industrial and commercial sites but limit building heights to 14 stories and floor-area ratio to 7. Vanderbilt Atlantic Holdings’ proposal was for 18 stories with an 8.8 FAR. Exceeding M-Crown’s parameters would create a dangerous precedent, community board members warned.

“It would be very difficult to get back to the 6 to 7 FAR that has been outlined for Atlantic Avenue,” said board member Gib Veconi during the December virtual meeting.

Community board approvals are advisory, but this one seemed essential for Vanderbilt Atlantic Holdings because Cumbo said she would only support a plan endorsed by Community Board 8.

In Li’s case, M-Crown was as much of a blessing as a curse. Sure, the vision restricted density, but it helped the developer and the board’s land use committee reach common ground.

“If you saw the framework, the community wanted to see density here,” said Li.

Vanderbilt Atlantic Holdings made some cuts, reducing the FAR to 7.2. But it was not enough. In May, the committee voted 14-2 to reject the revised plan. And in July, Adams — the mayoral front-runner — also recommended against it.

Normally, these rejections would weigh down the rezoning application as it moved on to the City Planning Commission and City Council for a final verdict. But in a twist, the developer, recalling Cumbo’s deference to the community board, went back to the land use panel to work out a compromise.

The result was an agreement to lower the height on some sides to 17 stories, reduce the bulk by 10 percent and shift density from one side of the project to another. Low-rent units would be slashed to 54 from 95, but they would be affordable to people with even lower incomes.

The land use committee voted 17-3 for the revised plan, calling it “a rare opportunity to secure truly affordable housing.” But the full community board’s vote of 14-8 with eight abstentions at a heated virtual meeting was technically short of a majority.

Adding fuel to the fire, Brisport said that the market-rate housing would lead to gentrification. “This seems like something that is being railroaded through by the developer and by the current councilwoman,” Brisport said at the meeting.

Brisport, a Democratic Socialist who represents the district in Albany, noted that Cumbo’s term was coming to an end this year. He suggested not voting until next year, although the city’s strict timetable on rezoning reviews does not allow for that.

Ironically, Brisport’s opposition might have helped Li’s team win Cumbo’s favor. Brisport ran against the Council member in 2017, bashing her for negotiating a rezoning that allowed BFC Partners to redevelop a long-vacant Crown Heights armory into mixed-income housing, a recreation center and offices for nonprofits.

Although he lost the Democratic primary by 40 points, Brisport got under Cumbo’s skin. Their relationship only got worse as the socialist upstart was elected to the state Senate last year. Cumbo’s office did not respond to a request to comment.

Setting a precedent

Vanderbilt Atlantic’s fight to leave its mark on Downtown Brooklyn’s nascent skyline is not quite over.

The developer is still battling McDonald’s in federal court. The fast-food giant claims the developer improperly raised rents by using a flawed appraisal process to force the restaurant out of a lease that runs until 2039. Vanderbilt Atlantic denies that and alleges that McDonald’s failed to cooperate with the appraisal process spelled out in the lease.

What the saga means for future rezonings is also up for debate.

The 840 Atlantic Avenue project differs from others seeking a rezoning such as Two Trees Development’s River Ring residential complex in Williamsburg and Eichner’s towers in Crown Heights. For one, the Prospect Heights parcel has no historic significance.

“It’s a single-story McDonald’s,” said Eugene Mekhtiyev of IMC Architecture. “It’s not a beacon of the community.”

Other than some union support, Eichner faced blanket opposition: Neighbors, Botanic Garden donors, local elected officials and the mayor lined up against him. That was not the case at 840 Atlantic Avenue.

“You just had anti-development groups. They didn’t link up with a powerful constituency,” said a New York City developer who requested anonymity.

And Li had some political tailwinds, notably de Blasio administration support and Cumbo’s acrid relationship with Brisport.

Still, the developers of 840 Atlantic Avenue played their cards right and will take their win. Li is not cashing in his chips just yet, though. He declined to give any construction timeline until the McDonald’s lawsuit is resolved.

“To me, this is the beginning of the process,” he said.