A missing wife. A torso floating in the bay. A friend killed, execution-style, in her own home.

It’s the stuff true-crime stories are made of. But only in one case did the trail lead back to the grandest stage of them all: the Manhattan skyline.

Robert Durst, a convicted murderer who died Monday at 78, hadn’t been a part of the family business, the Durst Organization, for nearly three decades since he was passed over in the succession plan in favor of his younger brother, Douglas. But he still carried a family name that is royalty in New York real estate, conjuring up images of some of the city’s most recognizable buildings and carrying serious political and civic clout. That association meant that his every misdeed became a national headline, his life documentary fodder and a source of constant frustration and heartache for the Dursts.

“Bob lived a sad, painful and tragic life,” Douglas said in a statement Monday. “We hope his death brings some closure to those he hurt.”

Dynastic disturbance

The origin story of the Durst empire is a classic tale of New York grit: schmatta peddlers who became moguls.

Arriving in the city in 1902 from Austria with no English, no connections and $3 sewn into a lapel, Joseph Durst began selling children’s clothes from a pushcart, according to the New York Times. He soon worked his way up to partner at a garment factory — “The New Durst Way: No Salesmen! No Unnecessary Expenses. Just Plain, Solid Merchandise,” reads an ad seen by the Times — and bought his first property in 1915, at 1 West 34th Street. His sons Seymour, Royal and David came into the business after World War II, and expanded its purview into development, putting up office towers on Third Avenue and stitching together a sizable assemblage in then-seedy Times Square.

Seymour’s sons, Douglas and Robert, joined the fray in the mid-1970s, but Robert had a difficult working relationship with the clan.

“He’d be sitting in the family meetings on the edge of his chair,” Jonathan Durst said to the Times of his father, David, “never knowing what Bob would say or do.”

In 1982, Robert’s first wife, Kathleen McCormack, disappeared. Though some of her friends and family suspected Robert, given the breakdown of their marriage and his reportedly violent outbursts, he was never charged in the case. His spokesperson and staunchest defender during the saga was an old friend named Susan Berman.

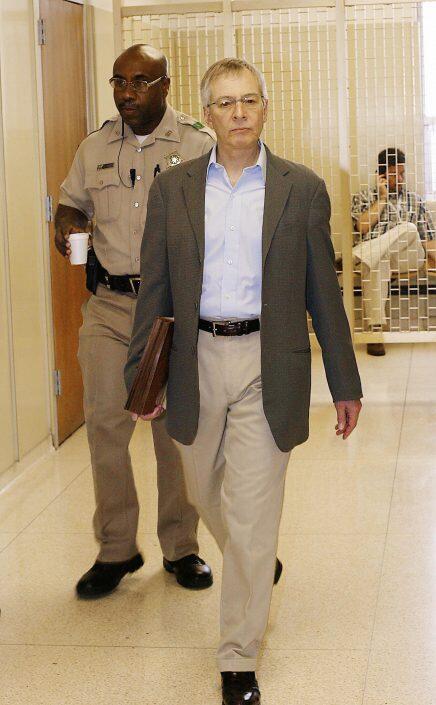

(Source: Getty Images)

In 1994, Seymour and David tapped Douglas to head the Durst Organization, and Robert walked out. By 2006, he would give up all claims to the family fortune in exchange for a $65 million payout.

Today, the Durst portfolio is valued at about $8 billion and spans 13 million square feet of prime office space and nearly 3 million square feet of rental units. Though Seymour’s mantra was never to buy real estate you can’t walk to, which kept the empire concentrated in prime Midtown Manhattan, the next generation branched out, with projects including a $1.5 billion development in Halletts Point in Astoria — slated to include over 2,000 housing units across 2.4 million square feet — and a $2.2 billion redevelopment of Penn’s Landing on the Philadelphia waterfront. In November, the company launched leasing at Sven, a 67-story, 958-unit rental in Long Island City.

4 Times Square (Source: Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat)

1 Bryant Park (Source: Wikipedia/Chris6d)

“Bob has always been a burden for me and my immediate family,” Douglas told the Times in 2015. “But it has not impacted our relations with others or the Durst Organization’s ability to do business.”

Exit West

In November 2000, Robert bought a $77,000 engagement ring for Debrah Lee Charatan, a New York real estate broker. According to the Guardian, he proposed to Charatan just one day after learning that he was once again under investigation in the McCormack case. (Charatan, who Robert gave power of attorney and control over his estimated $100 million fortune, went on to found BCB Property Management, a real estate investment firm that amassed a substantial multifamily portfolio in the mid-2010s.)

Robert later described the union as a “marriage of convenience,” telling his sister that “I had to have Debrah to write my checks. I was setting myself up to be a fugitive.”

In December 2000, Berman’s body was discovered in her Beverly Hills home. She had been shot in the back of the head.

In 2001, the torso of a drifter named Morris Black was found floating in Galveston Bay, Texas.

Investigators of both deaths found ties to Robert Durst.

Black was living in a Galveston rooming house, across the hall from where Robert, sometimes pretending to be a mute woman, was staying. According to Robert’s court testimony, he and Black got into an argument, and his gun went off in the scuffle, accidentally killing Black. He then dismembered Black and dumped his body parts in the bay. He was charged with murder but fled, triggering a 45-day manhunt which ended when he was caught stealing a chicken sandwich in a Pennsylvania supermarket. In his trial, he successfully argued that he had acted in self-defense and was acquitted, in part due to a lack of evidence: Black’s head was never recovered by investigators.

The Berman case took a lot longer to come together, and it was only in 2015, after a reinvestigation into her death, that Robert was charged with her murder. Prosecutors said Robert wanted to ensure that Berman would not reveal what she knew about the disappearance of his first wife. In September 2021, Robert was convicted of first-degree murder. He was sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole. (His death while his appeal was pending means that his murder conviction will be vacated, as per California law.)

During the trial, the prosecution heard from 80 witnesses, including Douglas, who said he believed his brother wanted him dead.

“I hired security today,” Douglas testified last June. “I have fear that my brother has threatened to kill me, and I have fear that he may have the means to do so.”

But the most damning evidence came from Robert himself, in a series of confessionals during an interview with a deputy Los Angeles County district attorney after his arrest in 2015 and in a hot-mic moment on HBO’s smash-hit documentary on his life: “The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst.”

“What the hell did I do?” Robert said off-camera during a visit to the bathroom. “Killed them all, of course.”