You can lead a socialist to the fountain of knowledge, but you can’t make her drink.

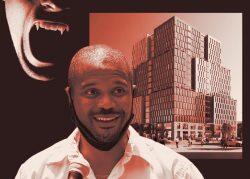

That comes to mind upon reading City Council member Kristin Richardson Jordan’s rationale for opposing a Harlem apartment project with about 650 market-rate and 250 income-restricted apartments.

“The market-rate housing is what’s driving up the property values and driving up the cost of living and causing a lot of struggles with congestion in the area and has a big environmental impact,” the rookie Council member told City & State.

To his credit, reporter Jeff Coltin did not leave the claim unchallenged, as writers often do. His next sentence, which included links to three research papers, was: “The effect of new construction on cost of living is hotly debated, though multiple recent reports suggest that building new units has decreased rents in the area, at least in the short term.”

One has to wonder how long folks like Jordan will cling to the notion that they can preserve affordability by denying new housing for six-figure earners. Where, exactly, do they want these New Yorkers to go? Without development in the city, the choices are:

- Existing housing

- The suburbs

Option 1 means outbidding and displacing the occupants. Clearly, Jordan does not want that.

Option 2 means the high-earning household will become SUV-dependent and have a carbon footprint several times greater than if it had moved to Harlem. Suburban migration also shifts tax revenue out of the city, and public funding away from the subways and to commuter rail and highways.

During a Real Deal webinar two years ago, Inwood rezoning opponent Paloma Lara refreshingly declared that she wanted high earners to stay in the city so their taxes could be spent on social services. Just as long as they did not live in Inwood.

As Jordan’s comments revealed, the belief persists that the affluent will not affect rents or displace people if they simply find housing somewhere else.

New housing in high-income areas will help them do that, which is why the de Blasio administration rezoned Soho. But the market-rate housing built in Soho will be unaffordable even for most professionals. Some will still have to push out into other neighborhoods.

Harlem, for one.

Which brings us to the second character in our story: Bruce Teitelbaum.

A member of Rudy Giuliani’s inner circle before he had a falling out with the former mayor, Teitelbaum is not a prolific developer. He pursues projects here and there, typically working with other investors. The Harlem project is, for him, a big one.

Read more

His group’s original plan for the buildings they bought on West 145th Street between Adam Clayton Powell and Malcolm X boulevards was to raze them and build 49 market-rate units. He could do that without a rezoning, leaving the Council no say in the matter.

But about five years ago, Teitelbaum got a call from our story’s third character: Al Sharpton.

During the Giuliani years, Teitelbaum’s boss and Sharpton were as bitter as enemies could be. The mayor rallied his base by banning the activist from City Hall, and Sharpton rallied his by slamming Giuliani at every opportunity.

But in purchasing the assemblage, Teitelbaum became Sharpton’s landlord. When the wrecking ball arrived, Sharpton’s National Action Network would lose its home.

Sharpton could hardly imagine a better location for his nonprofit. Moreover, both he and Teitelbaum had mellowed over the years, and Giuliani was out of the picture.

Hence, Sharpton’s proposition: Rezone the site for a larger project, which would require affordable units under the city’s inclusionary housing law, and include space for a new National Action Network headquarters. The Harlem market was strong enough for everything to pencil out. All Teitelbaum would need was City Council approval.

That brings us to the final character, Suri Kasirer. As the city’s No. 1 or No. 2 highest-grossing lobbyist every year, she knows a thing or two about getting projects like Teitelbaum’s One45 through the Council. But it probably did not take a persuasive pitch for her to land the $10,000-a-month gig: Teitelbaum is her husband.

Normally, rezonings can be stopped by the local Council member. Only once since 2009 has a member failed — Ben Kallos in November, because his colleagues viewed his opposition to a New York Blood Center project as pandering to privileged Upper East Siders and hindering efforts to cure sickle-cell anemia.

Jordan’s hand is similarly weak. Like Kallos, she has not endeared herself to colleagues, and Sharpton probably has even more allies on the Council than the Blood Center did. Making the plan nearly bulletproof, Teitelbaum and Sharpton added another politically potent tenant: the Museum for Civil Rights.

City & State noted that the board of the foundation planning the museum is co-chaired by Sharpton and includes former de Blasio deputy mayor Lilliam Barrios-Paoli, Democratic and gay-rights activist Allen Roskoff and Teitelbaum himself. Completing the developer’s Dream Team, the foundation’s lawyer is Howard Weiss, head of the land use practice at Davidoff Hutcher & Citron.

Howard S. Weiss of Davidoff Hutcher & Citron LLP (Source: Davidoff Hutcher & Citron)

The chamber’s tradition of member deference remains strong, but it has always had exceptions, and they all appear to be present for One45: influential allies, an astute brain trust, public benefits (affordable housing and the museum) and an inexperienced, isolated opponent.

It’s hard to see Jordan lining up 25 colleagues to vote against the rezoning when it comes to the Council in May or June. She faces an unappetizing choice between being marginalized and negotiating to allow a project she despises.

There is a third option, albeit one that politicians rarely consider. Rather than ignore the science and keep company with climate deniers and anti-vaxxers, Jordan could consult the data and change her mind.

Freed of her honest but ill-conceived notions, she could negotiate for more public benefits and vote in line with her principles, which are undoubtedly to make New York a more vibrant, environmentally responsible and affordable city.