Andrew Chung’s deal to acquire the HSBC tower in Midtown may have been doomed from the start.

After agreeing in December to buy the building at 452 Fifth Avenue for $855 million, the founder of Innovo Property Group rushed to put down a $30 million deposit.

But Chung had a secret: He didn’t have the equity to make the deal happen. To close by the April deadline, sources said, he was banking on a high-wire plan to raise around $200 million while lining up an acquisition loan. When he couldn’t come up with the cash, the seller, Eli Elefant’s Property & Building Corp., went ahead and refinanced the property, all but killing any hope that Chung could resurrect the deal. Chung lost his deposit and a whole lot more.

A former executive at the Carlyle Group, Chung rose quickly as an independent real estate player, thanks to a prescient bet on last-mile warehouses. But he made crucial mistakes in his bid for the HSBC tower, according to several people who detailed how the deal fell apart. The high price he’d agreed to — nearly $1,000 per square foot — became unworkable when interest rates rose. He told the seller and his lender, JPMorgan, that he had secured the equity when he hadn’t, the people said. He was counting on too many moving parts coming together and when they didn’t, he was unable to come up with a solution.

“It’s indicative of what’s happening and will continue to happen in commercial real estate, particularly with office,” said Madison International Realty’s Ron Dickerman, who noted rising interest rates are forcing everyone to reevaluate pricing, tenant demand and cap rate assumptions.

Chung declined to comment for this story.

Real estate is a messy business. Lawsuits and partnership disputes are a given. But gambling with a deposit before even lining up money to close on a Midtown skyscraper? That’s unheard of, industry insiders said.

Closing on the building would have boosted Chung’s status among New York’s real estate elite.

No longer just a scrappy industrial assembler, he would own an architectural icon overlooking Bryant Park. Instead, his failed bid represents something else: a gambler who couldn’t buy in.

Move fast and break things

The office property at 40th Street and Fifth Avenue is unusual. At its base lies a 10-story Beaux-Arts building constructed for the Knox Hat Company in 1902 and designed by John Hemenway Duncan, architect of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Arch at Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza.

In 1981, Republic National Bank built a 30-story zig-zagging glass tower behind the Knox Building, and the two structures were combined into one.

“The tower bears down over the old building, turning this strong classical structure into a quaint little toy,” Paul Goldberger, the former New York Times architecture critic, wrote in 1984.

Reeling from the financial crisis in 2010, HSBC, which had absorbed Republic National Bank years prior, sold the building to Property & Building Corp. for $330 million and leased back 10 floors. PBC’s U.S. arm spent $100 million on renovations, and rumors persisted that it was looking to sell.

By 2021, PBC had decided to liquidate its U.S. assets and repatriate its funds to Israel. Last fall, the firm tapped Eastdil Secured’s Roy March and Gary Phillips to market the property, with pricing guidance of $850 million, or just under $1,000 per square foot.

The property attracted interest from some of the biggest players in New York City and abroad. Waterman Clark, the investment firm led by former Brookfield Properties head Ric Clark, the German fund Commerz Real, the Chera family’s Crown Acquisitions, George Comfort & Sons, Savanna and Hines all participated in the bidding, sources said. Michael Shvo also made an offer.

Chung, who left Carlyle in 2015, was one of the first investors to anticipate the surge in demand for last-mile warehouse space and put together a string of eye-catching deals, including spending $75 million for to buy 2505 Bruckner Boulevard in the Bronx, where Innovo would develop a 20-acre industrial facility. He became known for paying top dollar to lock down properties he felt were undervalued.

rnrn“The deal just sat there, and the longer it sat there, people became less interested.”rnrn

Chung splashed down a $30 million deposit for the HSBC tower, but most of that money was not his. The funds were pooled together from a number of investors, including Howard Lutnick, chair of Newmark and financial services firm Cantor Fitzgerald, according to sources. Lutnick did not respond to a request for comment.

To secure the deal, Chung told PBC and JPMorgan (which gave him a term sheet for about $650 million in debt) that he had the equity to close, according to sources. In reality, he was still working on raising it, effectively passing around a hat and collecting $10 million here, another $10 million there.

Chung reached out to Guggenheim Partners, Crown Acquisitions and his usual backer, Hong Kong-based investment firm Nan Fung, for funding, sources said, but he couldn’t scrounge up enough cash to close.

“He was shopping this everywhere,” said one person familiar with the deal. “The deal just sat there, and the longer it sat there, people became less interested.”

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve, intent on combating inflation, was raising interest rates. Additional financing on top of the JPMorgan loan would likely be a lot more expensive. Taking out a mezzanine loan would also be pricier, cutting into Chung’s already-thin profit margin.

Read more

Chung was also taking a risk with his repositioning plan. The 1980s-era building required millions in renovations, including a new lobby and space for new tenants. It also needed a replacement for HSBC, which occupied two-thirds of the building but was leaving for Tishman Speyer’s The Spiral in Hudson Yards. Other tenants include law firm Baker McKenzie and investment manager Man Group.

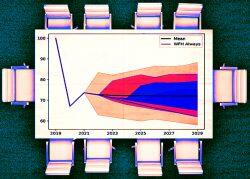

But Chung only budgeted a small amount for initial improvements, according to an investor presentation deck obtained by The Real Deal. He was planning to close and then head back out into the market to either sell or recapitalize with a new partner who would fund the required work. People who’ve been involved in deals of this size said it was a risky way to plan for necessary improvement costs.

His investor deck shows that after one to three years, he planned to sell the property or recapitalize at a valuation of $1.2 billion, with roughly $116 million worth of capital expenditures credited to the next buyer. More than half that money would go to tenant improvements and leasing commissions; the rest would have been for building upgrades.

As the April 1 deadline approached, PBC agreed to a one-month extension on the condition Chung up his deposit by $5 million. The two agreed to another short-term extension on April 26 but only on condition that Chung release it from escrow — an all-or-nothing final attempt to close the deal.

On May 15, news broke on the Tel Aviv stock exchange that Chung had trouble financing the deal. A day later, on May 16, the extended deadline came and went.

The news was devastating not only for Chung, but for PBC. Its Israeli parent was relying on the sale to finance its acquisition of a stake in Bayside Land Corp, a real estate company, for 3.1 billion Israeli shekels, or about $890 million. PBC had to rush to find new financing to close the Bayside acquisition, which it eventually did.

There was talk after the deadline passed that Chung could get back in and close on the purchase. But in early July, those hopes died. PBC closed on $385 million in financing from JPMorgan at a higher rate of SOFR, plus 4.5 percent to replace its maturing loan for the HSBC building.

Chung made his reputation in unglamorous industrial properties, but may have dented it on the most visible asset class of them all: a Midtown office tower.

As a rival developer put it: “On deals of this magnitude, you’re really only as good as your reputation.”