Already this year, blue-chip developers have battled holdout tenants and holdout sellers. But how about a holdout neighbor?

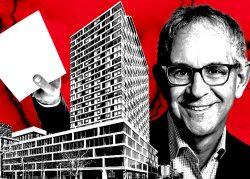

MRR Development, the firm founded by Anand Mahindra, Rotem Rosen and Jerry Rotonda, has spent four years and nearly $100 million building a 10-lot assemblage on the corner on Lexington Avenue between East 56th and East 57th streets. But before it can join the glass giants of Billionaires’ Row, the developer needs access to a squat building on the western edge of its assemblage, 124 East 57th Street.

That building owner isn’t playing ball, according to a request for entry filed with the New York State Supreme Court.

For a project like MRR’s 28-story, ODA Architecture-designed development, New York’s building code requires a pre-construction survey documenting the condition of all adjacent buildings. The firm will also need temporary access to its neighbor’s building to install netting and building protections to keep it and passersby safe during construction. The city won’t allow MRR to move forward on its project without these protections, and according to court filings, the neighbor has been anything but neighborly.

After months of fruitless negotiations, MRR is now asking the court to grant it access to the neighbor’s structure so it can conduct its pre-construction survey and get building.

Filings depict a numbingly repetitive negotiation between the two buildings that reads like something out of the movie “Groundhog Day.” As the lawyers for each building owner negotiated the terms of an access agreement, MRR’s attorney repeatedly asked for his counterpart’s input. But according to an email thread shared in the lawsuit, he heard nothing back.

In one instance, the developer’s lawyer sought comment on a draft agreement four different times between April 4 and April 19. The wait dragged on a month more as Bension DeFunis, in-house council for Solil Management working as the neighbor’s attorney, cited Passover and an emergency for the delays. DeFunis finally sent his comments on May 19.

“You have simply wholesale rejected nearly 100% of Project Owner’s edits,” wrote Eric Thorsen, an attorney from Quinn McCabe representing MRR, in a letter to DeFunis. “The edits you have made are nothing more than a reversion to your initial draft, with no substantive progress, and in certain respects backwards progress.”

Read more

Neither attorney responded to requests for comment.

Thorsen went on to say that the project couldn’t wait much longer, and threatened to seek a court-ordered license. That got DeFunis’ attention, as the lawyers held a call in early June to try to hammer out an agreement. But the two sides couldn’t agree on a monthly access fee, with DeFunis asking for more than $4,000 more per month than MRR’s best offer.

The case has to feel like déjà vu, as MRR previously persuaded a court to grant it access to the neighboring building during the demolition phase of the project after the owner was “unreasonable” during agreement negotiations.

“Adjacent Owner has made clear, as it did during the prior demolition phase license agreement negotiations, that it has no intention of entering into a reasonable license agreement,” wrote Matteo Lattanzio, another Quinn McCabe attorney representing MRR in the most recent filings.

DeFunis has yet to respond to the proceedings.

A handful of safety nets and some building access may not sound like a lot, but on a path as boobytrapped as skyscraper development, even a small speedbump can be costly.

“The inconvenience to Adjacent Owner,” Lattanzio wrote, “is slight compared to the hardship to Project Owner if the license is refused.”