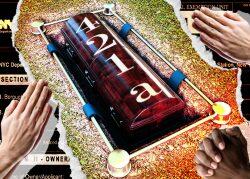

A few months ago, Douglaston Development’s Jed Resnick thought he’d discovered an opportunity in the death of the 421a tax break.

It wasn’t in condominiums or luxury rentals, the only types of apartment projects that developers say are financially viable without the incentive.

The silver lining Resnick saw was in the new building filings that had flooded city permitting offices since late last year.

As the real estate industry called on state lawmakers to renew or replace 421a, developers prepared for its June 15 expiration by scrambling to finish plans and paperwork. Their hope was that the city’s Department of Buildings would greenlight their projects in time to sink pilings in the ground before the tax break lapsed.

But Resnick suspected that many of them wouldn’t have the capital or expertise to build the large projects they envisioned. And that would create an opening for developers who did.

“It’s a lot harder than it looks,” Resnick said in April. “These projects get to be complex.”

But in the months since the tax break expired, developers say, they have found few 421a-qualified sites attractive enough to buy.

Industry experts believe many of those plans will languish while the city faces a housing shortage that’s only expected to get worse. Some projects could even die on the vine, as they must be completed by June 15, 2026, to get the property-tax abatement.

Site rush

In the final months of Affordable New York — the last iteration of the 421a program — developers effectively staged a run on the Department of Buildings.

Data reviewed by the Real Estate Board of New York shows the city issued 665 permits for new buildings in the fourth quarter of last year — 37 percent more than the quarterly median over nearly 14 years of data. In the first three months of this year, approvals ramped up to 689, the most in any quarter since 2014.

Before 421a expired in 2016, filings for new apartment buildings surged, then plummeted after it lapsed — until Albany reinstated the incentive more than a year later. The rush to file was in part because developers expected the new version to be less generous, which it was.

This time around, developers had the same fear but were also worried that 421a might disappear forever. That concern has grown since Gov. Kathy Hochul’s proposed replacement, 485w, failed to pass before the legislative session ended in June. Some lawmakers had made it clear more than a year ahead of time that they wanted 421a gone for good.

Again, builders raced to get plans filed and foundations laid, thus qualifying their projects for 421a before 35-year property tax breaks for largely market-rate buildings became a thing of the past.

Now what?

Douglaston’s Resnick was hardly alone in believing that many of the developers behind the rush of filings lacked the resources or intent to execute their 421a projects.

“A lot of folks rushed to get in under the deadline, and I think some are deciding it’s too much work to try and move forward and they’d rather just sell,” said Laszlo Syrop, head of acquisitions for the Hudson Companies.

“A lot of folks rushed to get in under the deadline, and I think some are deciding it’s too much work to try and move forward and they’d rather just sell,” said Laszlo Syrop, head of acquisitions for the Hudson Companies.

With interest rates much higher than they were at the start of the year, some may be struggling to secure construction loans. Others may have never intended to build in the first place, hoping to get their sites qualified for the tax break and then flip them.

“I think a lot of the guys that are selling, those that are grandfathered-in, are not real developers,” said Slate’s David Schwartz. “They’re just sort of landowners that wanted to capitalize on the break expiring.”

Even before 421a expired, the tax break boosted the value of any development site that qualified for it.

Read more

The incentive waives property taxes on multifamily projects for 25 years — owners only pay what the city had been collecting previously on the site — and discounts the tax bill for another 10 years after that. Even though 421a requires developers to set aside some units as affordable, it makes land far more valuable than sites that do not qualify for it.

“I think there was an expectation for sellers that 421a is going away, so I’m sitting on gold, right?” said Schwartz.

A site at 487 West 129th Street in Harlem, marketed by Cushman & Wakefield as 421a-qualified “with a footing in the ground,” was asking $29 million in late September, or roughly $187 per buildable square foot.

By comparison, the average price in July for Northern Manhattan development sites was $155 per buildable square foot, according to an Ariel Property Advisors report.

The gold-mine theory has not quite panned out. Multifamily developers say landowners have oversaturated the market with 421a-qualified sites and priced them aggressively, leading to few trades.

“The premium that people put on [421a sites] is not being justified by the market,” Schwartz said.

A cooling commodity

The problem isn’t just excess supply and high prices. Developers say many recently filed plans are a mess. And because of the 2026 completion deadline, many sites may not be worth buying.

“Just because the project has a footing in the ground and is technically eligible for the program doesn’t mean that it’s a layup,” said Syrop.

Some plans may have been rushed, Syrop said, meaning “the quality of the architecture may not be really there.” Layouts hustled through may be substandard or exceed the carbon emissions limits pending under Local Law 97. Either shortcoming would require a redesign.

Developers would need amendments approved by the Department of Buildings, which could take a while given the volume of filings and staffing shortage at the agency, where nearly one in four positions is unfilled.

“That creates a lot of pressure — all those projects going through at the same time,” Syrop said.

Tack on a couple of years for construction and account for supply-chain and labor-related delays, and developers are faced with a swiftly closing window to evaluate, purchase, fix and finish a project in time to nab the break.

Brett Gottlieb, a partner at Herrick Feinstein specializing in 421a, said he sees a “very limited, finite period of time” in which development sites will be able to sell.

“I think these sites, in general, will probably lose their luster within about a year and a half,” Gottlieb said.

Taking the plunge

Despite those hurdles, some 421a sites have changed hands in recent months.

Gary Barnett’s Extell Development took over a Feil Organization project at 356 Fulton Street in Downtown Brooklyn in early June. The firm signed a long-term ground lease with Feil for $85.9 million — $181 per square foot based on Feil’s planned 475,000-square-foot structure. Feil’s paperwork called for (appropriately) 421 apartments, 30 percent of which would be affordable under the program.

Barnett, who specializes in luxury condos, could ditch Feil’s 421a plans entirely. Even if he goes with it, he isn’t picking up a slipshod project. Feil secured permits in November and had been piecing the assemblage together since 2015.

JLL’s Bob Knakal, who brokered the deal, said it was the only trade of a 421a site he could think of over the past several months. Rosewood Realty Group’s Aaron Jungreis said he had no examples to offer.

One smaller 421a-qualified site in Gowanus did sell in late September: Brooklyn-based Tankhouse paid $40.7 million for a parcel at 452 Union Street with plans for a 24-unit rental building.

Gottlieb said projects with fewer units likely have a better chance of selling. Developers don’t need as much time to build them, giving them a bigger cushion.

“If you have a two-year project, for example, then you better be underway by early 2024,” he said. “If you have a four-year project, then you better be starting right now.”

Insult to injury

Although it’s unclear how many projects will go unbuilt, sentiment in the industry seems universal that the loss of the tax break will exacerbate the city’s housing shortage.

“The result is going to be less housing coming online at a time when we need it really desperately,” said Syrop.

Developers had certainly warned that if the tax break went away, they would eschew mixed-income rentals for higher-end projects. After buying a site at 470 Kent Avenue in Williamsburg in 2019, Naftali Group had planned two rental buildings with more than 400 apartments, 30 percent of which would have been affordable. Now, Miki Naftali says his firm is moving forward with condominiums.

“What choice do we have?” Naftali said in May. “We’re going to sell them; we’re going to make money. How does that help anybody?”

The city needs to build an estimated 560,000 housing units by 2030 to keep pace with population growth and make up for a decade-long deficit in new construction, according to a study by consulting firm AKRF commissioned by the Real Estate Board of New York.

If qualifying sites go unused, it will depress new supply and likely accelerate rents that only just plateaued after six months of record highs.

Developers say that if Albany renews the program, they can’t count on lawmakers to extend completion deadlines on existing sites. Even if they did, it would be too late for some projects, Syrop said.

“If you move forward and the design is suboptimal and the program gets extended, it doesn’t necessarily mean you can improve that building that’s out of the ground,” Syrop said.

Many aren’t banking on the incentive’s return anyway. After lawmakers dismissed Hochul’s proposed replacement, several far-left candidates won their August primary elections, which does not bode well for a reboot of the tax break.

“I think that’s a total gamble,” Schwartz said of an extension. “And I think the people who gamble will be left with sites. So if I were a landowner who wanted to sell, I would sell now.”