In a quiet part of Lower Manhattan sits a shiny, unfinished supertall. Its list of suitors reads like a who’s who of New York real estate, players who hoped that the project, at 125 Greenwich Street, would be Downtown’s answer to 432 Park Avenue.

It didn’t turn out that way.

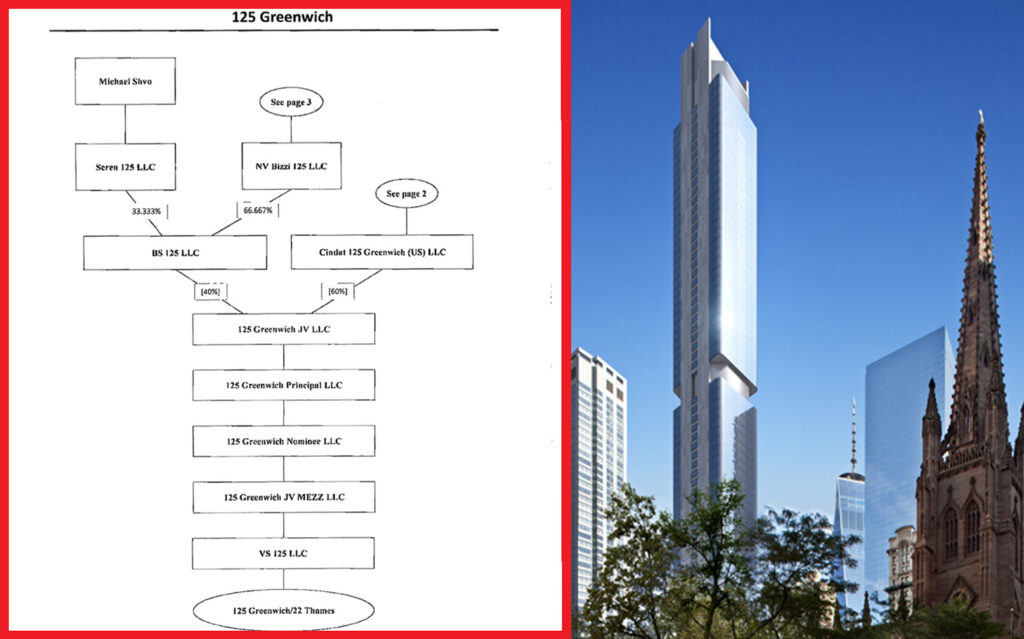

For years, 125 Greenwich remained in limbo, brought to a halt not by the usual plagues of development, such as construction defects or labor disputes, but by the capital stack. Internal feuding among the development team and a lender who got cold feet led to delays and lawsuits and contributed to sluggish sales. The project was further hobbled by foreclosure threats and the pandemic. Instead of an ode to creative dealmaking and cutting-edge design, 125 Greenwich, located two blocks south of One World Trade Center, became one of New York’s most prominent stalled sites.

But it has now been resurrected. In early February, the partners restructured and scored $313 million in financing from Northwind Group to finish construction. Fortress Investment Group, the powerful distressed investor who held the debt on the tower, is now an equity partner. Sales are expected to relaunch this year.

“We were able to restructure with a formula that will allow us to complete the project,” said Alessandro Pallaoro, managing director of Bizzi & Partners, a co-sponsor and public face of the development.

The project might not make money anytime soon, but if completed it will rank among the biggest comeback tales in recent New York real estate history.

To understand how 125 Greenwich was brought back to life, The Real Deal interviewed many of the key players involved, from those in the spotlight to those pulling the strings behind the scenes. According to them, the Rafael Viñoly-designed tower ran into a perfect storm of problems. It was undercapitalized, its Chinese partner and lenders were taking heat in their home country, and the condo market turned for the worse, leading to weak sales.

A towering opportunity

In 2012, Steve Witkoff and Fisher Brothers acquired the site for $87.5 million. They tapped Viñoly, the Uruguayan starchitect behind 432 Park, to design what would be the tallest residential building in Lower Manhattan.

Two years later, as Manhattan’s condo market was roaring, Witkoff and Fisher sold the site to Michael Shvo for $185 million, nearly $100 million more than they paid for it. Shvo, a buccaneering new development broker turned luxury condo developer, brought on Howard Lorber’s New Valley and Bizzi & Partners and nabbed $170 million in financing from Singapore-based United Overseas Bank and Taro Pharmaceutical Industries. Cindat, an affiliate of a major Chinese asset manager with strong government ties, came in as a limited partner with a $55 million preferred-equity investment. Howard Michaels, the pugnacious financier who founded Carlton Group, chipped in equity as well.

“Frankly, you guys would be nuts not to sign this EB-5 money up.”

— Howard Michaels, Carlton Group

“I thought this project was perfect to create a supertall Downtown, something that did not exist,” Shvo told TRD in 2018.

The design was simple: The tower would rise 912 feet and 88 stories, with curved corners and shiny blue glass windows. But unlike most other luxury towers that offer big-ticket buyers the highest floors as penthouses, here the top three floors would boast amenities, including a 50-foot lap pool with views of the city. The projected sellout was just under $900 million, filings with the New York Attorney General show.

But getting things moving proved difficult. By 2015, the developers were in talks to land around $500 million in construction financing from United Overseas Bank, but the deal couldn’t close. Forced to look elsewhere, the developers sought cheap, short-term funding from EB-5 investors.

“As discussed, none of you are looking to write a big equity check for the actual development of the property,” Michaels wrote in an email to the development team. He pressed them to take on $174 million in funds from Nicholas Mastroianni II’s U.S. Immigration Fund, a major EB-5 regional center that was raising capital for U.S. developers through the controversial cash-for-green card program.

“Frankly, you guys would be nuts not to sign this EB-5 money up,” said Michaels, who died in September 2018.

They landed the EB-5 funding, but trouble emerged. In 2016, Michaels’ Carlton Group, which arranged the financing, sued the development group over commissions on the EB-5 loan and an equity injection from New Valley. That same year, Shvo was indicted by the Manhattan District Attorney on tax evasion charges. A source close to the matter said Shvo’s indictment threw the financing into disarray — banks can take a dim view of sponsors caught up in criminal matters — eventually forcing the partners to buy out his stake in 2018.

Sales finally launched in 2017, but were cold. Insiders put part of the blame on the location.

The site sits in a part of Lower Manhattan that some consider a dead zone. It’s not in the heart of the Financial District and sits across from a giant hole where Silverstein Properties and Brookfield Properties plan to build Five World Trade Center. Moreover, units at 125 Greenwich were asking an average of $2,800 per square foot, a premium above projects in the area.

The partners started talks with other experienced condo developers such as Witkoff and Michael Stern’s JDS Development to come in and help see the project through. But the numbers weren’t working.

“The return on investment just wasn’t compelling,” one source familiar with the matter said.

In 2018, the project secured a debt package from four Asian lenders, including United Overseas Bank, Bank of China, China Merchants Bank and Wing Lung Bank, plus a junior mortgage from China Cinda Asset Management. The total financing came to $473 million.

Construction moved along, but by the first quarter of 2019, only about $50 million of units had sold, according to a lawsuit filed by United Overseas Bank. Prices had to be slashed in order to meet lender-imposed sales deadlines.

By December 2019, the developers and their sales team at Douglas Elliman — which Lorber runs — scrambled to sell up to $60 million worth of condos in less than 90 days, according to a court filing. They needed to cut some unit prices by around 20 percent, reducing the average price per square foot of those units to $2,100.

“It’s a complicated loan — you can’t get it done in one week.”

— Ran Eliasaf, Northwind Group

But Bank of China wouldn’t budge. The lender had a $200 million piece of the financing and didn’t want to risk losing its returns. It refused to fund the loan, citing weak sales. With a $200 million gap in the capital stack, construction stopped in 2019 with the building agonizingly close to completion.

“At the point in time there was a political shift in China,” said one source familiar with the matter. “So [the Chinese government] started blocking a lot of capital outflow.”

Once Bank of China was out, United Overseas Bank had had enough. It sold its distressed loan to Florida-based BH3, for $195 million, at par.

“As we approached the end of 2018, we saw some writing on the wall that was reminiscent of 2007,” Greg Freedman of BH3 told trade publication Multi-Housing News at the time. “125 Greenwich represents to us the first real validation that the bull market that we’ve been in for the past eight or nine years has kind of come to an end.”

BH3 pursued a foreclosure, but then sold the loan to Fortress for $230 million in early 2020. The private equity firm, majority owned by SoftBank Group, had a knack for swooping in and buying the debt on troubled condo projects at a bargain. (The lender famously bought Kent Swig’s Sheffield condo project at a foreclosure auction during the Great Recession for pennies on the dollar.)”

Adding to these issues with its lenders, Cindat argued it wasn’t liable for guaranteeing the loan, according to legal filings. Multiple sources referred to them as “difficult.”

But Covid delayed Fortress’s plans to foreclose. Instead, Fortress and the developers moved to restructure: Fortress would convert its debt to equity and kick in more money to complete the project. It also took out Carlton Group, New Valley and Cindat’s equity positions. USIF also converted its debt to equity. At the same time, the project landed financing from Northwind Group, an alternative lender known for condo inventory loans.

“It’s a lot of details you have to underwrite and check,” said Ran Eliasaf, CEO of Northwind. “It’s a complicated loan — you can’t get it done in one week.”

Now the money is finally in place, though the environment 125 Greenwich finds itself in is a challenging one: New York’s new development market took a dive in the second half of 2022, according to data provider Marketproof, with higher mortgage rates taking their toll on buyers.

Still, the developers, battle-scarred though they might be, have the will to move ahead.

“Given all the challenges, all that happened,” Bizzi’s Pallaoro said, “we are still here until the very end.”‘