Even before regulators seized Signature Bank, shaking regional lending markets, rent-stabilized building owners were worried.

Not about Signature, though. About their buildings’ finances. In fact, they were counting on Signature to help.

Valentina Gojcaj, who manages a mostly rent-stabilized, 700-unit portfolio, recently tried to refinance a loan on an eight-unit building, only to find national lenders wouldn’t touch it.

“The property is basically underwater,” Gojcaj said, pointing to the rent law and Covid arrears squeezing the building’s revenue while inflation bloated its operating costs.

“[The bigger banks], they didn’t want anything to do with the property,” Gojcaj said. “We finally found a regional bank that, with personal guarantees, allowed us to pull a loan out.”

She is one of many owners of the city’s 900,000 rent-stabilized units struggling to pay their debts.

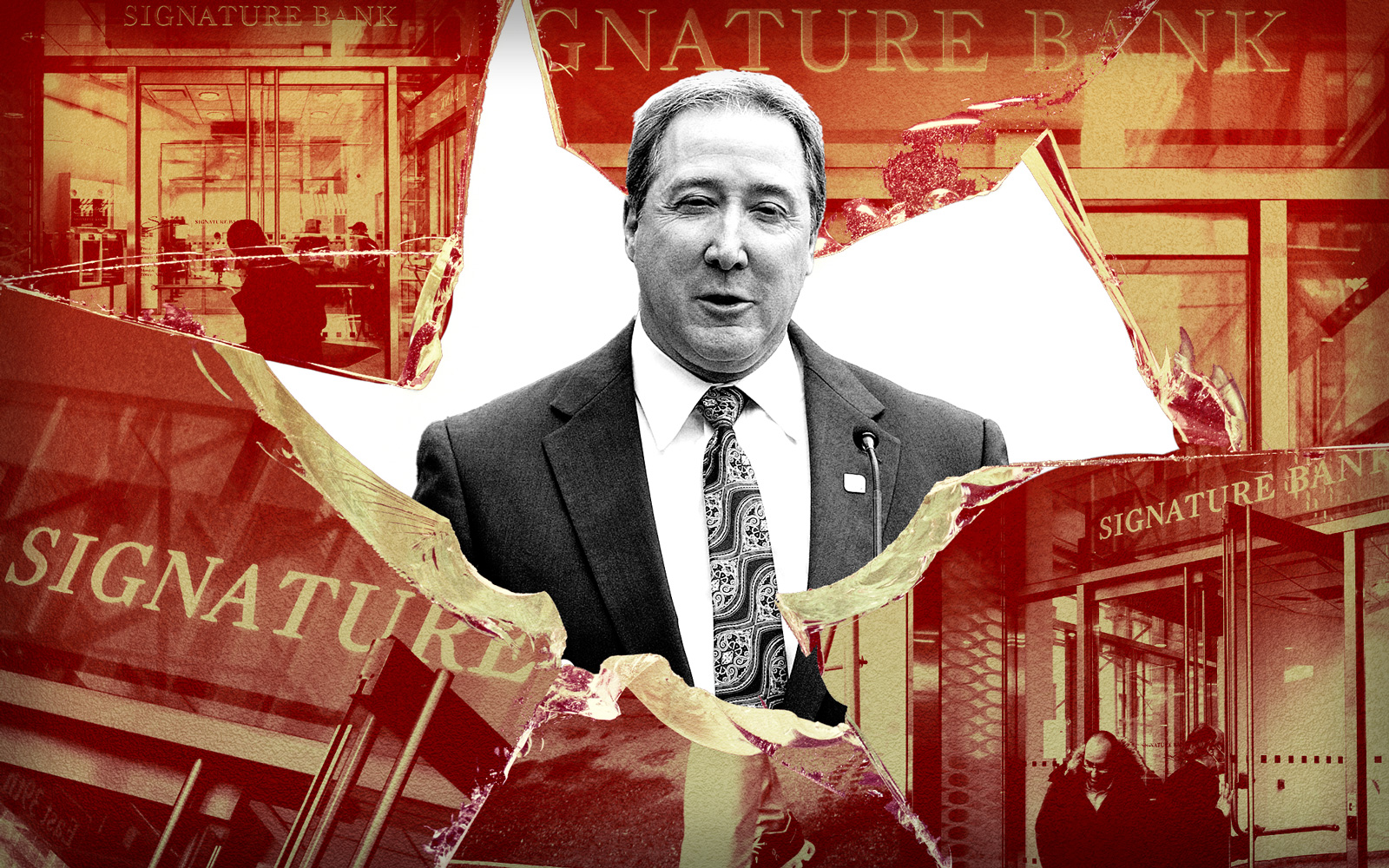

Signature was a major lender on those properties. Its failure Sunday, on the heels of tech lender Silicon Valley Bank collapsing in California, led to fears that other regional lenders would face bank runs or otherwise become unable to lend to the landlords who depend on them.

Even if cash-strapped owners can persuade national banks to refinance their buildings, it would entail higher fees and rates than they are accustomed to paying.

That’s an unwelcome prospect for landlords already in dire straits. Some will face foreclosure when their mortgages come due, if not sooner.

Confidence problem

Whether or not regional lending dries up depends on how clients of smaller New York banks react to Signature’s collapse.

Anecdotes paint a scene similar to the scenario that crippled Signature.

“Today, I’ve gotten no less than 30 text messages from other landlords that are pulling their money from regional banks out of fear that something bad’s gonna happen,” Michael Shah, whose firm Delshah Capital holds three large loans with Signature, said Tuesday.

“What we are afraid of is a snowball effect,” Gaia Real Estate’s Danny Fishman told The Real Deal Monday after a weekend spent yanking funds from regional institutions.

“As soon as rumors start, there’s a run on the bank,” he said. “And no bank can survive a run.”

Customers have continued to withdraw money despite regulators’ assurances that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and Federal Reserve would make Signature and Silicon Valley Bank depositors whole.

The government backstop ended a freefall Monday of regional bank stocks, but markets and clients remain ill at ease.

San Francisco-based First Republic Bank’s share price plummeted 62 percent Monday and yesterday its credit rating was cut to junk over concerns that account holders would pull their deposits, Bloomberg reported.

It’s unclear if Signature’s closest competitor in the rent-stabilized space, New York Community Bank, is suffering a similar siege. A spokesperson for the bank has not responded to requests for comment.

Some landlords have dismissed such banks as viable alternatives.

“The regional bank balance sheet option is literally off the table right now,” Shah said. “Every regional bank in the country today is in danger as a result of the past three days.”

Even if the government’s $25 billion small loan initiative covers outflows, insiders expect regional lenders will become more conservative.

Go-to lender

For rent-stabilized landlords, Signature and other regional lenders offered competitive rates and market knowledge that became crucial when the 2019 rent law passed.

The legislation severely curtailed owners’ ability to raise rents and diminished the value of their buildings, in some cases “to virtually nil,” said Jay Martin, executive director of the Community Housing Improvement Program, which represents landlords.

But while national lenders, such as Chase, cut the appraised value of rent-stabilized properties by 30 percent for loans in process once the legislation passed, Gojcaj remembers, regional lenders were more forgiving.

“They’ve known the market forever so they’re better lenders,” she said.

With regional bank’s lending appetite in limbo, landlords say they will likely turn to larger banks to refinance when mortgages reset or mature.

In the case of a reset, typically every five years, owners can allow the mortgage’s fixed rate to adjust to the current rate environment or refinance with another bank.

Letting the reset play out is a bad move for most borrowers now that rates have jumped 4.5 percentage points in the past year.

But finding a new lender will be expensive — if it’s even possible.

Big banks, big fees

Ken Fisher, a real estate attorney at Cozen O’Connor, said some big banks will probably step in to fill the gap, but at a premium.

“If you’re a banker and the economics of any given deal will allow you to charge the interest rate you’re looking for, you may be willing to give the customer the benefit of the doubt.” Fisher said.

But owners who have come to depend on the affordable rates of regional banks now worry that higher interest and fees, coupled with attorneys fees, could be unfeasible.

“It’s expensive to do a refinance,” Gojcaj said.

Even owners who have time left on their loans are likely to be hit by those higher costs.

Under the 2019 rent law, Martin said, more owners have come to rely on loans to cover rent losses and one-time repair costs.

“If regional bank lending starts to slow down or stop with fewer and fewer options for owners to supplement their operating losses, more and more rent-stabilized buildings will be in distress.” he tweeted.

Foreclosures loom

Without access to affordable debt, attorneys say, owners could lose some of their rent-stabilized properties.

“I think that’s a very likely possibility,” Fisher said.

Already, lenders have filed foreclosure suits against owners who bought regulated properties at high prices, expecting to raise rents to cover debt payments, only to see the new law crush their projections.

“Those folks who were basically treating apartment buildings like a commodity to be traded, they’re the ones that are going to feel the pressure first,” Fisher said.

Signature borrower Sugar Hill Capital Partners, for one, has faced multiple foreclosures in recent months on properties it acquired before the law changed.

Even long-term owners who were not looking to significantly raise rents will likely feel the pain over the next few years if they have loans coming due.

“They nonetheless are going to get squeezed by fewer lenders, more conservative lenders and rising interest rates,” Fisher said. “They probably had some restless nights even before Signature.”

Read more