Geraldine Tyler owed $2,311 in property taxes, a sum that by 2015 ballooned to more than $15,000 thanks to interest and penalties.

A year later, the local government auctioned off her one-bedroom condominium unit for $40,000.

The sale was executed by Hennepin County, Minnesota, but, eight years later, has implications for New York and other states. Today the U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments in Tyler’s challenge to the county’s practice of seizing and selling properties with unpaid property taxes — and pocketing any windfalls.

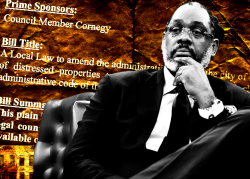

Similar questions have been raised about New York’s Third Party Transfer program, which does not automatically reimburse owners for any difference between what they owe and what their seized property is worth. In the program, the city gives properties with property tax debt to new owners for redevelopment as affordable housing.

“New York is in a minority of states that keeps the surplus,” said Tyler Martinez, a senior attorney with the National Taxpayers Union Foundation, who filed a brief in support of Tyler. “Other states have no problem giving back what is due to the homeowner.”

The city has not used the Third Party Transfer program to take properties since 2018, amid calls to reform the program and ongoing litigation challenging its constitutionality. An official at the Department of Housing Preservation confirmed that the city is watching the Tyler case.

The Supreme Court is being asked to clarify whether government must compensate property owners for the difference in value between their tax debt and seized property. The petition filed on Tyler’s behalf points to confusion caused by a 1956 Supreme Court decision, which let New York City sell a property for $7,000 to satisfy $65 in unpaid water bills.

The sale did not represent an unlawful taking, the court ruled, because the owner had been notified of the impending foreclosure and had ample opportunity to pay the debt.

City officials have argued that the Third Party Transfer program similarly gives property owners enough of a chance to keep their homes. Owners get notices and can enter payment plans to gradually settle their debt.

The decades-old New York case has been used by many municipalities to defend their tax collection programs in court. If the Supreme Court were to reinterpret that decision in its Minnesota ruling, New York and other states may have to revisit their tax enforcement systems.

Ivy Perez, deputy director of policy and research at the homeownership advocacy group Center for NYC Neighborhoods, posited that a ruling in Tyler’s favor could “pose a lot of questions to states across the country.”

“I think at the very least it would spook a locality where they have a program like this,” she said.

A class-action lawsuit filed in 2019 by Brooklyn homeowners who lost their properties to Third Party Transfer argues that the mechanisms available to avoid it are “illusory.” Critics say the program, along with the city’s lien sale, fails to provide enough notification before properties enter foreclosure.

“Taking the surplus equity value in private property without compensating owners is flagrantly unconstitutional; it always has been,” Yolande Nicholson, one of the attorneys representing the property owners in the class action, said in a statement. “For individuals and families whose only means of building intergenerational wealth is the current and long-term surplus value in the property, the decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in Hennepin will undeniably affect a family’s right to hundreds of thousands, if not millions of dollars.”

But the systems have defenders.

In a brief filed in support of Hennepin County, the National Tax Lien Association and others warn against inviting changes to “one state’s tax-sale statutes without being able to confidently account for the immediate and long-term effects on the statutory schemes in the other states.”

They argue that ruling the Hennepin County system unconstitutional would open up a can of worms nationwide, because each system to deal with a property’s unpaid taxes is unique.

“Statutory schemes for assessing, levying, and collecting taxes are fickle. They emerge from a host of trade-offs, concessions, and policy directives during the legislative process, resulting in an interdependent statutory scheme,” the brief states.

Both the city’s lien sale and transfer program were launched during the Giuliani administration as ways for the city to collect money from delinquent properties without taking ownership of them.

The programs function differently. In the lien sale, the city sells property debt such as unpaid tax and water bills to an investment trust, which tries to collect as it charges hefty interest. If the owner does not pay, the trust forecloses and sells the property at auction. The former owner can apply to state court for the equity surplus.

The city has not authorized a lien sale since 2021 because it is politically unpopular, but Ana Champeny, vice president for research at the Citizens Budget Commission, said the sale has been effective in “reducing delinquency and generating that critical revenue.”

The city’s financial plan estimates it will yield $80 million in revenue this fiscal year and in each of the next four. But if liens are not sold, the city’s loss could be greater: Without the deterrent, delinquencies could increase, Champeny said.

The city estimates that each 1 percent increase in delinquency would cost it $1.7 billion over five years.

The lien sale and third-party transfer have faced similar criticism, including that they disproportionately affect communities of color. Even without pressure from the Supreme Court, the City Council and Adams administration have wanted reforms. The state legislature, meanwhile, has proposed changing foreclosure rules, including mandating that certain owners get the surplus if the sale of their property more than covers their debt.

“Equity is such an enormous part of the wealth of most Americans,” Perez said. “It cannot be ignored that there is such an outsized effect on so many communities, and that these communities are often communities of color.”

Read more