What should have been an easy sale on the Upper East Side has turned into a year-long ordeal for a veteran Corcoran broker.

The broker, who requested anonymity for fear of retribution from the building’s co-op board, had a unit at Emery Towers in contract within a month of its listing last spring, only for the buyer to be rejected by the co-op board despite supposedly good financials and being well-liked by the board.

The broker relisted the unit and soon landed another buyer, only to have the same thing happen.

Months of confusion finally came to an end, the broker said, when the explanation came trickling through the grapevine: The co-op board deemed the price too low.

“Now we’re going back at it, and we’re pretty much being upfront with the buyers,” said the broker. “We’re probably going to have to gross up the price a little bit to satisfy all the owners.”

Co-op boards can veto buyers without having to provide a shred of reasoning, and sometimes do so when they feel a pending sale would devalue the building.

David Kaufman, co-op board treasurer at Emery Towers, denied the claim the board rejects deals based on price and cast doubt on the buyer’s contact with the board, saying members don’t meet buyers until their financials are approved.

Kaufman said the board recently held a meeting to discuss what the board looks for from a buyer, like their income-to-debt ratio and liquidity. He said the meeting drew a relatively low turnout and that residents overall seemed generally happy with the board’s approval process.

As buyers’ interest in co-ops wanes, claims like what the broker believes happened at Emery Towers appear to be a growing problem, residential agents say.

“People on the board don’t like when sales go really low in a building because they own shares in a corporation, so it’s like lowering the stock,” said Compass broker Vickey Barron. “If a stock goes really low, every member who owns the stock is getting hurt.”

But some boards use a work-around to show the world a higher price than the buyer actually pays.

It works like this: The board makes its expected sale price known, and if buyers are not willing to pay it, the seller offers various credits to make up the difference. Aside from the lender, if there is one, nobody outside the deal knows concessions were given, let alone what they were worth.

Offering hidden concessions to close a deal isn’t necessarily unethical, but according to brokers and attorneys, the devil is in the details.

A seller covering closing costs or paying the transfer tax, as condominium developers often do, is widely seen as acceptable. But when co-op boards compel the use of rebates or credits that reach a certain level — particularly when they exceed 3 percent of the price — attorneys and brokers get squeamish.

Critics say excessive credits throw off future comps, leading buyers to overpay based on the listed price of past sales in a building.

Let’s start with the fact that this is fundamentally dishonest.

The practice also adds another layer of complexity for brokers navigating an already lengthy and opaque co-op application process.

“There are certain lawyers that say you can’t do it, or shouldn’t do it,” said Shaun Pappas, a real estate attorney at Starr Associates. “Certain lawyers say 3 to 5 percent wiggle room, some lawyers say you can do more than that. I haven’t seen much authority written on it either way.”

Tax issues also come into play. Transfer taxes, capital gains taxes and flip taxes are all based on the sticker price, not the actual price, so agreeing to a higher price in exchange for concessions can have unexpected consequences for buyers when they later sell.

Beyond that, some notable names in the industry oppose the practice on moral grounds.

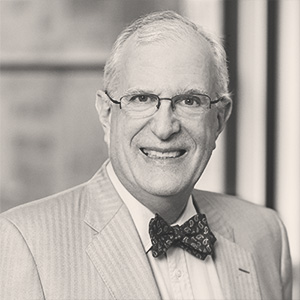

“In theory, we were all raised to do business in an above-board manner,” said Frederick Warburg Peters, president of the brokerage Coldwell Banker Warburg. “Let’s start with the fact that this is fundamentally dishonest.”

Peters said he knows of deals where concessions exceeded 10 percent of the sale price, though he declined to provide specific examples.

“It’s almost always in the hundreds of thousands of dollars,” said Peters. “It’s phantom money.”

The broker in the Emery Towers transaction perceives no choice but to inflate the price to get a deal done.

“We’re basically remarketing the property after a second turn-down, but we know whatever price we settle at, we’re going to be adding 6 percent to it,” the broker said.

That will most likely be more than $100,000, considering the price mandated by the board.

Tracing the history, frequency and scope of the practice is all but impossible. The New York Times wrote about it in 2012. Peters said he noted an uptick when the market cooled recently and also in early 2020, when the pandemic hit.

The practice appears relatively common, though by all accounts it occurs in a minority of deals.

“We’ve all had that experience, but it’s never put in writing, ever,” said Barron, the Compass broker.

Boards that engage in the practice include those at The Sovereign at 425 East 58th Street and The Imperial at 55 East 76th Street, according to agents who work in those buildings. One with a history of business at The Sovereign said its board will stretch a price, but not beyond a certain point.

“I know it exists but I know for a fact the board doesn’t like it,” said the broker. “They don’t like the way it looks.”

Some see concessions as a clever way to close deals in a tough market.

“To me it’s just another weapon in your toolbelt when it comes to negotiations,” said Mike Fabbri, a Nest Seekers broker.

The Real Estate Board of New York declined to weigh in. “REBNY does not regulate co-op pricing and negotiations,” a spokesperson said.

Co-op boards’ ability to set minimum prices stems from their unchecked authority to reject buyers — a power that has come under fire in recent years. Bills were introduced in the City Council in February and in Albany two years ago that would require boards to provide a rationale for rejections. Past attempts have been defeated by co-op boards and their lobbyists.

The issue riled up attendees at the recent annual meeting of the Council of New York Cooperatives and Condominiums, an advocacy group for building board members.

“We’ve been battling this stuff for 40 years but it doesn’t let up. They’re out to get us,” said group president Marc Luxemburg, who accused brokers of conspiring against co-op boards to boost sales. “I’m sorry, it’s a fact: The principal interest group that’s pushing all of this is the real estate brokers, but it doesn’t come out in the public debate. That’s what it’s really all about.”

This article has been updated with comments from David Kaufman, co-op board treasurer at Emery Towers.

Read more