As large buildings struggle to comply with the city’s emissions cap, a select few face an overwhelming challenge.

Low-equity co-ops and rental properties that generate their own power have discovered it’s going to cost a lot of green to go green.

Consultants hired by the buildings, which total 33,860 apartments, estimate the bill at a staggering $2.6 billion — nearly $77,000 per unit, including financing — for the upgrades to avoid fines under Local Law 97.

The cost was so high that a leading supporter of the emissions cap literally did not believe it.

“Get some second and third and fourth opinions on this,” said Pete Sikora, the climate campaigns director of New York Communities For Change. “I’m sorry, I think these are manageable, realistic objectives over time. These kinds of buildings should be making this leap.”

But Dan Weeden, president of Fidelity Energy & Sustainability, which consults for two of the complexes that have their own co-generation plants, said numerous strategies have been explored. “The scrapping of these systems and the electrification of buildings in the city has tremendous price tags associated with it,” he said.

For instance, replacing gas stoves with electric ones means running 220-volt lines to every unit. “To rewire buildings of this construction type and vintage is no small undertaking,” Weeden said. At $15,000 to $20,000 per apartment over 33,860 units, the low end of the estimate is $507 million.

“Many of these co-ops have sought out … third, fourth and fifth options,” said Weeden, whose clients include Manhattan’s Penn South, with 2,820 units, and the 982-unit Big Six Towers in Queens. ”If Mr. Sikora has a solution that does not have these onerous costs associated with it, we would love to know what they are.”

Complexes with cogeneration also include the Bronx’s Co-op City, with 15,372 units, Brooklyn’s Amalgamated Warbasse Houses with 2,585 units and Spring Creek Towers with 5,881 rentals, and Rochdale Village in Queens with 5,860 co-op units, plus some smaller ones.

The law spares these affordable complexes from fines until 2035, but the penalties pile up quickly from there. Through 2050, Co-op City, Warbasse, Penn South and Big Six would be dinged for $575 million, given the huge amount of oil and gas they use. Co-op City’s fines would be twice as much as the others combined — $121 per unit, per month in the first year alone.

The law was intended to reduce emissions, not collect penalties. For these buildings, however, compliance would cost more – a lot more – their consultants concluded.

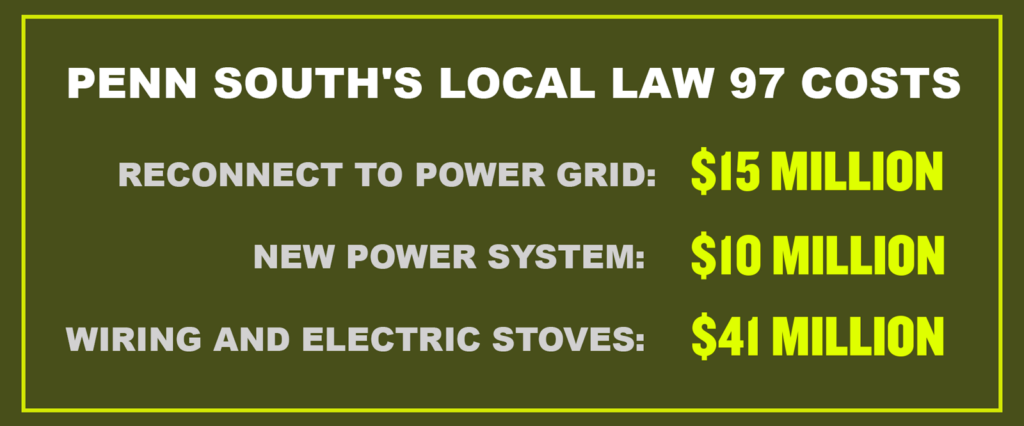

Penn South’s bill for its 10 buildings southwest of Penn Station would be $66 million, or $23,400 per unit, and work would have to start next year. But raising the maintenance by 20 percent ($193 per month for a two-bedroom) may require regulatory approvals. Big Six, at just one-third the size, needs $53 million for upgrades and financing — $54,000 per unit. Maintenance charges at the Mitchell-Lama co-op in Woodside would jump by 35 percent.

Many residents are low-income or elderly with fixed incomes and could not afford such an increase.

Ryan Dziedziech, general manager of Penn South, also known as Mutual Redevelopment Houses, said, “Trying to meet compliance for Local Law 97 has developed into a very costly endeavor for all buildings but especially private, not-for-profit affordable housing.”

That’s because decades ago, to save on electricity, these multi-building, multi-acre campuses were built with their own power plants utilizing steam and fuel oil, which at the time cost just 2 cents per gallon.

When oil prices spiked during the 1970s, the projects pursued energy efficiency. Penn South sub-metered its apartments, cutting electric usage by 16 percent in the first year, and added gas for a more efficient dual-fuel system. After Big Six built a cogeneration plant, Penn South followed.

The systems were desirable because the heat created as they generate electricity is used for heating and hot water. In the summer, the systems are used for cooling. And they keep running during citywide blackouts, which occurred in 1965, 1977 and 2012.

For many years, these campuses stayed connected to Con Edison but the fees to do so became too costly, and all but Co-op City left the grid. Reconnecting would be expensive but would help meet the city’s lofty emissions goals as the electric grid becomes greener.

The buildings have also explored solar power, but they are short on roof area and ground space for panels, and battery storage to supply power when the sun isn’t shining is extremely costly.

Generating cleaner power on site with fuel cells or renewable hydrogen, for example, would also cut emissions but be prohibitively expensive, Weeden said.

Penn South has become more energy-efficient. It replaced HVAC pipes in 2011 with a $25 million loan from the city in return for extending its tax abatement and affordability, which after other upgrades, now extends to 2052.

The 10 engines in its power plant use natural gas, diesel or both. It is spending $2.6 million to replace one diesel engine with a more efficient natural gas system.

“We anticipate having a two-to-three-year return on investment by reducing our diesel fuel usage,” said Dziedziech.

But none of that will be nearly enough. “Ultimately, compliance for Local Law 97 would require no fossil fuels to be burned on site and all equipment to be electrified,” Dziedziech said.

At Big Six, ditching Con Ed in 1980 has meant far lower heat and electricity rates — a key factor in the complex’s affordability, its board wrote in a March letter to Mayor Eric Adams pleading for financial and regulatory aid to comply with Local Law 97.

An engineering study advised Big Six to replace its diesel engines with highly efficient gas engines before Jan. 1, 2025. Otherwise, it might not get a new operating certificate for its power plant. The study also recommended reconnecting to Con Ed, which would cost more than $15 million.

All the upgrades would add up to nearly $34 million, Weeden said, yet still not guarantee compliance with the emissions cap. Big Six also needs $20 million worth of new roofs, facades and elevators. Assuming 6 percent financing, maintenance fees would rise by over 35 percent.

“The burning of fossil fuel for self-generation makes it impossible to comply with the law,” Weeden said. “Even if they went back onto Con Ed’s grid completely, they would still not comply with the law because the current grid is not clean enough.”

A spokesperson for the utility said, “Con Edison is a strong supporter of New York’s climate goals and we’re committed to building a grid that can carry 100 percent clean energy by 2040.”

But that’s five years after the fines kick in, and, grid improvements aside, it’s far from certain that enough clean energy will be available.

“We could spend all that money and still not comply,” Dziedziech said. “It’s cheaper for us to pay the fines.”

Even at campuses where the penalties would cost half as much as meeting the emissions cap, they would still be unaffordable to many residents. At Brooklyn’s Spring Creek Towers, formerly known as Starrett City, 60 percent of apartments are set aside for Section 8 tenants. The owner, a joint venture of Rockpoint and Brooksville, is under a regulatory agreement that caps rents. It was hammered out a year before Local Law 97 of 2019.

Upgrading the systems there and at Rochdale Village would cost tens of millions of dollars.

Not everyone is willing to shoulder the burden. The middle-income Queens co-op Glen Oaks Village has filed a lawsuit over the mandates, and the 800,000-member Homeowners for a Stronger New York is kicking off an ad campaign to pass the Parker-Bronstein Law, a state bill to provide property tax breaks for compliance. https://nypost.com/2023/04/30/co-op-owners-rebel-against-massive-nyc-climate-law-costing-millions/

“Here at Penn South, we are passionate about the environment and have been at the forefront of many sustainable initiatives,” said its board president, Ambur Nicosia. “Penn South and other affordable communities just need help to reach this goal.”

Even Sikora agreed. “It would be helpful for the city and state to subsidize these,” he said. “We have years to build the case for that and do these large-scale transformations.”

It will, however, take many years of planning and work to pull them off. The resident-run boards have already started preparing so they can figure out the financing and apply for loans and grants.

The costs for sprawling campuses like Rochdale Villages (13 acres), Co-op City (120 acres) and Spring Creek (140 acres) were not penciled out before Local Law 97 passed. The Urban Green Council, a nonprofit dedicated to decarbonizing buildings, did calculate in 2019 that if the 50,000 buildings covered by the law made improvements to comply, it would create a $16 billion to $24 billion market and 141,000 jobs.

It found residential buildings would need nearly $1 billion in upgrades by 2024 and another $6.9 billion by 2030 to avoid fines that kick in or some buildings that begin in those years.

The nonprofit might not have realized, though, the immense burden facing a handful of properties with fewer than 35,000 apartments. The organization did not return a request for comment.

Its website, however, states, “How can we retrofit almost 50,000 buildings in 10 years? It’s not going to be easy — or cheap.”

About that, there is no argument.

Read more