City Council members are advancing their own solution for the tens of thousands of vacant, rent-stabilized units: let tenants report hazardous conditions in them.

Their bill, they say, would help reveal the extent of the problem and how much financial aid landlords need to fix up and re-list the units.

Owners say it won’t do a thing to bring apartments online. They call it redundant legislation that would waste city resources.

The bill, introduced last spring, finally got a hearing Tuesday — a necessary step for it to have a shot at passing.

A tenant’s complaint would trigger an inspection by the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. If the city finds hazards such as mold or vermin, the owner would need to schedule a second check-in to show the issue has been cured.

Landlords may also be on the hook for inspection fees.

On its face, the bill offers tenants a direct line to report safety issues in neighboring vacant apartments, which advocates claim are shielded from city inspectors.

“There are no clear pathways — barring a warrant for access — to be in a vacant apartment to inspect it,” said Colin Kent-Daggett of the Coalition to End Apartment Warehousing, the tenant group backing the bill.

That means tenants with rats visiting from a neighboring unit have little hope of relief if their landlord won’t address the root of the problem, he said.

Not true, claimed the Rent Stabilization Association, a landlord group.

“HPD already has the power to write violations … if conditions in a vacant unit are impacting occupied units and causing the residents to suffer,” said Michael Tobman, director of membership and communication at RSA.

The agency can also bring owners to court for failure to cure those violations, he said.

“To create a second violation to be written against the vacant unit is a way to create additional violations for no real purpose other than to be punitive,” Tobman said.

Behind the bill is a theory that landlords are unnecessarily keeping rent-stabilized units vacant — which critics call “warehousing” — by claiming it would cost too much to make them rentable again.

Elected officials supporting the legislation say it would allow the city to better count vacant, rent-stabilized apartments and would offer a look inside units that landlords deem uninhabitable.

Official estimates of vacant unit counts have ranged from 20,000 to 60,000.

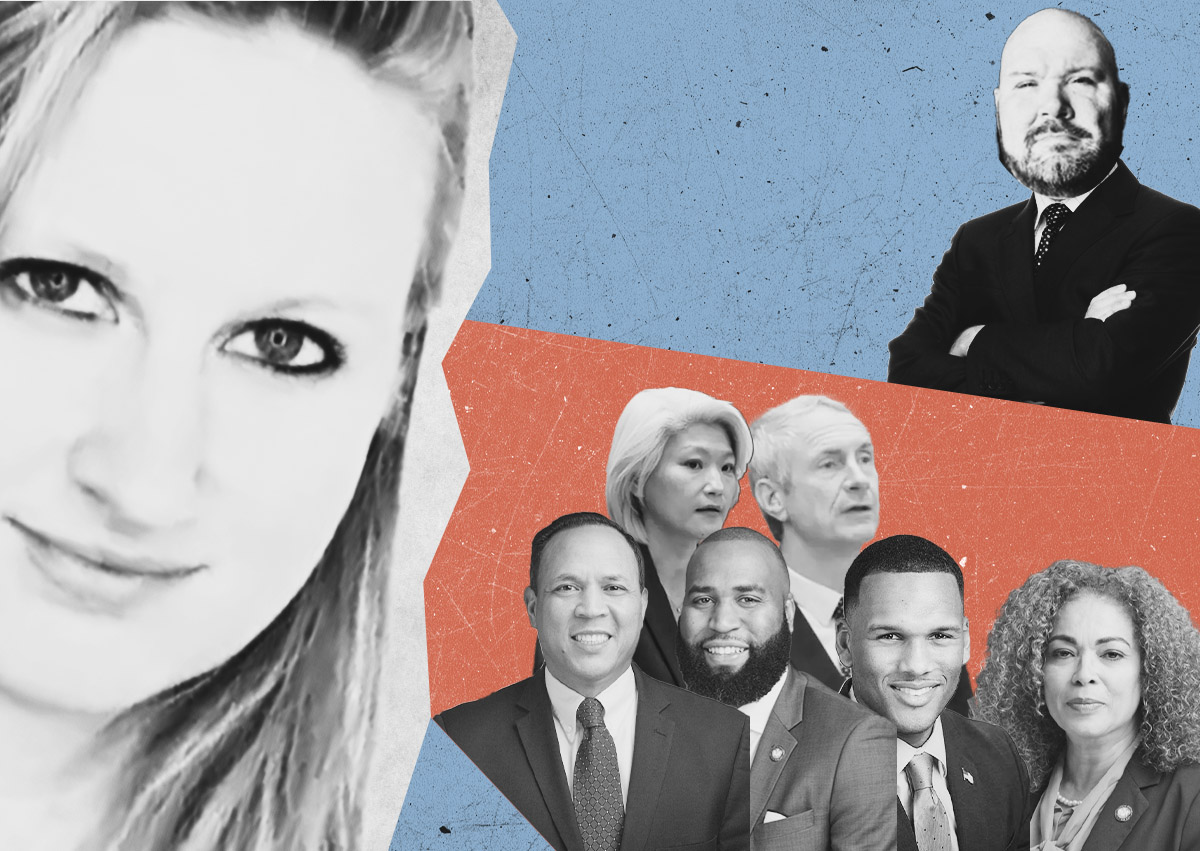

“I hear about warehoused apartments all the time but I don’t know how many there are,” said Council member Gale Brewer, a co-sponsor of the bill. “This is about data, data, data.”

The Community Housing Improvement Program, a landlord group campaigning for a one-time rent increase to return vacant units to the market, said the state housing agency already has data on registered stabilized units, and the city’s Department of Finance has counts of vacant units in buildings with 10 or more units.

Inspections triggered by the bill, the group argued, wouldn’t offer much more clarity — individual complaints do not produce a comprehensive tally of units or estimate repair costs — and would do nothing to bring apartments online.

“We need real solutions and housing policies that work.” executive director Jay Martin said. “Hopefully, the City Council will support solutions instead of wasting their time collecting more data that will likely be ignored.”

The Council’s ability to address the vacancy issue is limited. The state’s Division of Homes and Community Renewal oversees rent-stabilization and the state Legislature would need to be tapped to affect the 2019 rent law that blocked most pathways for owners to raise rents in stabilized apartments.

“We can’t do anything on the city level like they can on the state level,” Brewer conceded.

Another Manhattan Council member, Carlina Rivera, positioned the bill as a potential benefit to owners, saying transparency on vacant units would allow the city to “target landlords who may be in need of assistance so it can support landlords to make those repairs.”

The Council member pointed to the mayor’s $10 million Unlocking Doors pilot program that will offer landlords $25,000 per unit to repair vacant, rent-stabilized apartments. Owners have said that one-time infusion wouldn’t be enough.

In a press release Tuesday, CHIP asked the Council to draft a resolution in support of its state legislation.

Rivera said she’s not opposed to the idea but would need to look at the bill language, citing the importance of curbing gentrification that pushes out long-term and low-income tenants.

“I’m willing to work with anyone who wants to make housing more available to New Yorkers and increase affordability over all,” Rivera said.

Read more