An independent study this week affirmed what landlords have been saying for more than a year: the city has too many long-term, rent-stabilized vacancies and the number is only growing.

The Independent Budget Office analyzed state housing data and found 13,362 apartments had been empty for two consecutive years — up 8 percent from the previous year.

Meanwhile, the overall vacancy rate went down as Covid fleers returned. It fell to 5 percent from 7 percent as the number of empty apartments dropped to 42,000 last year from 60,000 the year before.

The differential is telling, according to landlord group the Community Housing Improvement Program. More long-term vacancies but fewer empty apartments overall shows that landlords were unable to rent out a subset of older units even as tenants flocked back to the city.

“The number of overall vacancies should be dramatically lower, but the current laws are forcing thousands of apartments to stay empty,” executive director Jay Martin said, noting that newer apartments stabilized through the 421a tax abatement likely drove the uptick in occupancy.

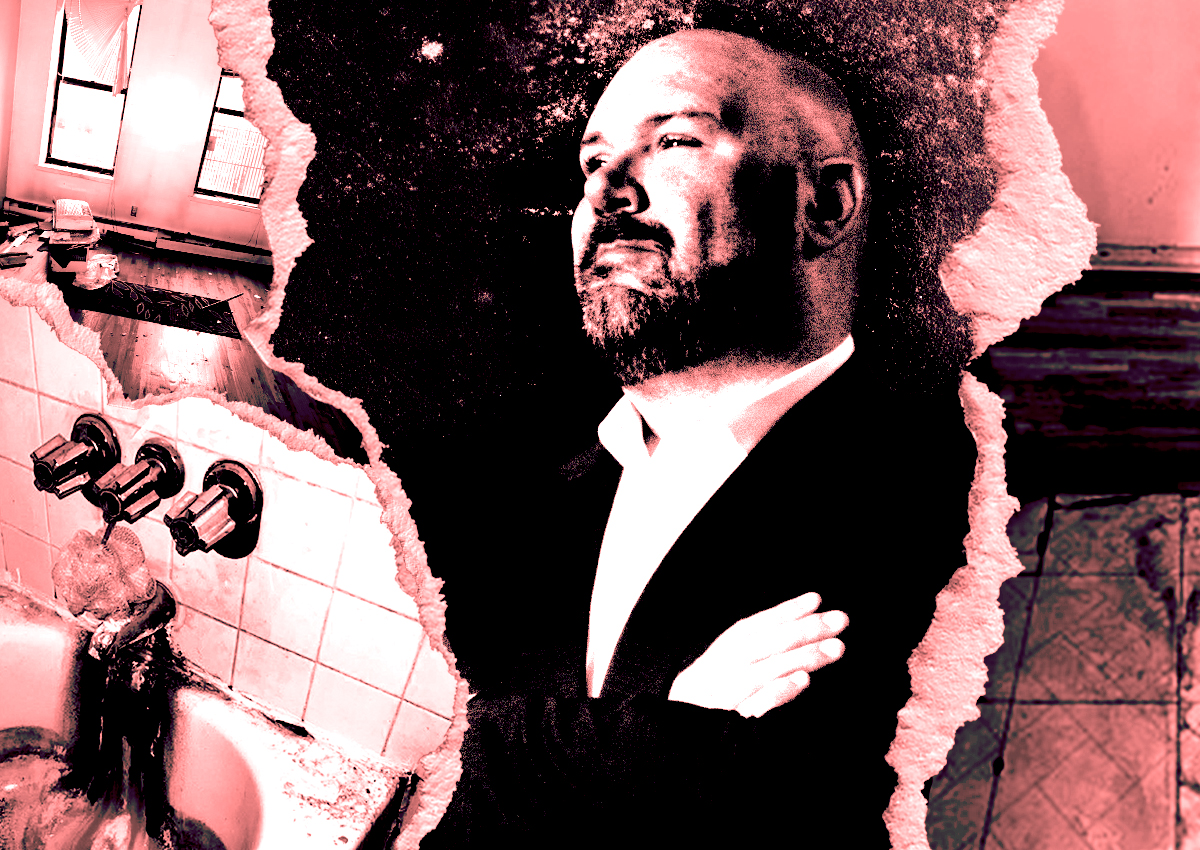

In early 2022, CHIP launched a lobbying campaign to shed light on rent-stabilized units’ staying empty since the 2019 rent law made it impossible for owners to profitably re-rent units requiring extensive repairs.

The legislation capped recoverable renovation costs at $15,000 over 30 years. Owners estimate the work needed to get apartments back online after long-term tenancies can cost $100,000 or more.

Stabilized tenants are entitled to lifelong lease renewals, and many only vacate upon death. Landlords are then left to fix up a unit that hasn’t been upgraded in decades, but cannot raise the rent nearly enough to recover the cost.

CHIP originally estimated about 20,000 units sat vacant as a result of the 2019 rent law. In the year since, estimates of vacant, rent-stabilized units have ranged from 40,000 to 60,000 depending on which government agency is doing the counting, although it has been difficult to pinpoint how many vacancies are caused by various factors.

Some landlords keep a unit vacant until one next door opens up, allowing them to combine apartments and set a new rent. The state is expected to close that loophole.

Moreover, the numbers are inexact. Each year, a number of owners fail to register their apartments. Some register late, missing that year’s count.

The IBO came up against those same hurdles.

The research office found about one-quarter of the 60,000 vacant units in 2021 had not been rented out the following year and two-thirds had been re-leased. The status of the other 12 percent could not be determined, meaning the vacancy problem may be greater than the data show.

Read more

Also, the numbers that IBO had to work with lag the current market by about 16 months.

Defenders of the 2019 rent reform could argue that IBO’s findings show that only a small percentage of the city’s roughly 900,000 rent-stabilized units are vacant because rent increases to pay for repairs are limited.

But CHIP said the uptick in 2022 is evidence enough the problem is getting worse.

“The data lags, the registration filings lag, but the trend is clear and proves our argument,” Martin said.

The group supports a state bill that would allow a rent reset for rent-stabilized apartments coming off long-term tenancies.