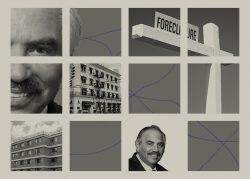

On Halloween morning, the tenants of 63 Tiffany Place rallied outside of their Carroll Gardens apartment building to ask the near impossible.

They wanted their landlord Irving Langer to sell them his building.

“Trick or treat, do not cheat, with the tenants, you must meet,” chanted the renters, activists and electeds, including New York City Comptroller and chorus director Brad Lander.

Langer was not in attendance — notwithstanding a cardboard cutout of the one-time 10th “worst landlord” — and did not respond to a request for comment.

His absenteeism was beside the point. The tenants’ demands were largely illustrative.

They’d tried to get Langer to sell before the buildings’ low-income housing tax credit, which had held units affordable for 30 years, expires in 2025. A nonprofit had agreed to buy the building and keep units affordable, they said, but Langer had cut off communication, leaving them with no leverage.

That would all be different if the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act passed.

“This is exactly what TOPA is supposed to stop and get us to focus on preserving what is left of the affordable housing in New York,” Assembly member Marcela Mitaynes, who sponsored the act, said of plans for Tiffany Place that she claims would raise rents and push out tenants.

The bill, which has been floating around Albany since 2020, gives tenants the first shot at buying their building if their landlord wants to sell.

It would pause a sale for several months so tenants could talk to the city about a subsidy, the bank about a loan and put together an offer, Housing Justice For All’s Cea Weaver explained. Tenants could come together to form a cooperative and collectively manage the building.

But more often than not, tenants use TOPA as a “negotiating chip,” Weaver said, referencing cases in San Francisco and Washington, D.C., which have passed versions of the bill.

For example, if tenants know their landlord wants to sell they may offer to waive their right of first refusal in exchange for a five-year lease.

Or, they can assign their TOPA rights to a nonprofit, which could buy the building — a strategy that would most benefit the Tiffany Place tenants. Under a nonprofit, the building could conceivably remain an affordable rental.

Weaver said TOPA has support in Albany — ”people like it” — but it’s unlikely anything will pass before TIffany Place’s LIHTC expires. That means Langer can sell, as activists claim he wants to do, and the new owner can raise rents to market rate.

What’s still foggy is whether Good Cause Eviction, another bill activists tied to the 63 Tiffany Place fight, will protect tenants from rent hikes when 2025 rolls around, activists said.

About half of the units at 63 Tiffany are rent-stabilized, meaning they won’t face a rent hike when the LIHTC expires, Maria Vaello-Calderon of TakeRoot Justice, which is representing 63 Tiffany Place, explained.

For the remainder, Good Cause should effectively cap rent hikes to 10 percent or inflation plus 5 percent, whichever is lower. If an increase exceeds that threshold, the tenant would have a defense against eviction in housing court.

Good Cause does not cover government-regulated units that are rent- or income-restricted, Vaello-Calderon said, meaning Tiffany Place’s non-regulated units won’t get the protection while the LIHTC, a federal subsidy, is in effect.

Once the LIHTC expires in March, the attorney said those tenants would presumably be covered by Good Cause. But the owner could argue in court that a large rent increase is justified, given the loss of the subsidy.

Read more