Mayor Eric Adams let his deputies take the lead on drumming up excitement for his legacy-making housing policy.

But after its approval Thursday evening, Adams stopped to talk to reporters at City Hall, and reminded them of the narrative that overshadowed the negotiations.

“People constantly stated, ‘Oh, Eric, you’re distracted … You’re distracted, you’re distracted.’ I think this is going to be a real part of a legacy and history that, no matter what they throw at us, we’re going to land the plane,” he said.

He was alluding to concerns that federal corruption charges against him would weaken the effort to pass the City of Yes for Housing Opportunity.

Sporting a hat that said “yes to housing opportunities” and flanked by First Deputy Mayor Maria Torres-Springer, he repeatedly referred to the text amendment as the “the most historical housing reform in the history of the city.”

The City Council, however, had chipped away at the City of Yes, making changes that will reduce how much housing it will create by 20,000 homes.

The modifications preserved parking minimums for new housing construction in much of the city, barred backyard accessory dwelling units in certain low-density areas, added affordability requirements to transit-oriented and “town center” projects and deepened affordability requirements for a new density bonus program.

But the administration, pro-housing groups and some developers took the win. Torres-Springer emphasized that the modifications did not eliminate any “major components,” and City Planning Director Dan Garodnick called the changes “thoughtful.”

Adams noted that the amendments to City of Yes were responsive to concerns raised by community members.

“We knew at the start of this that we needed to be willing to hear both sides,” he said when asked about the changes to the proposal. “I never go into negotiations expecting to walk away with everything I want.”

The changes were accompanied by a $5 billion commitment from the city for housing and infrastructure, with $1 billion of that money coming from the state.

AnneMarie Gray, of Yimby group Open New York, views the approval as a critical acknowledgement of the need to address the city’s housing shortage by making it easier to build. She said in a statement that if the full Council approves the text amendment, as is expected next month, it will be the “clearest sign yet that our leadership is capable of taking on big challenges.”

Build, baby, build

For the developers, the passage of City of Yes, even a diluted version, is a victory.

Real Estate Board of New York President Jim Whelan called it a “good day in the effort to produce much needed mixed-income rental housing.”

Developers support the removal of parking mandates because it enables them to add more housing, which brings in more revenue than parking spots.

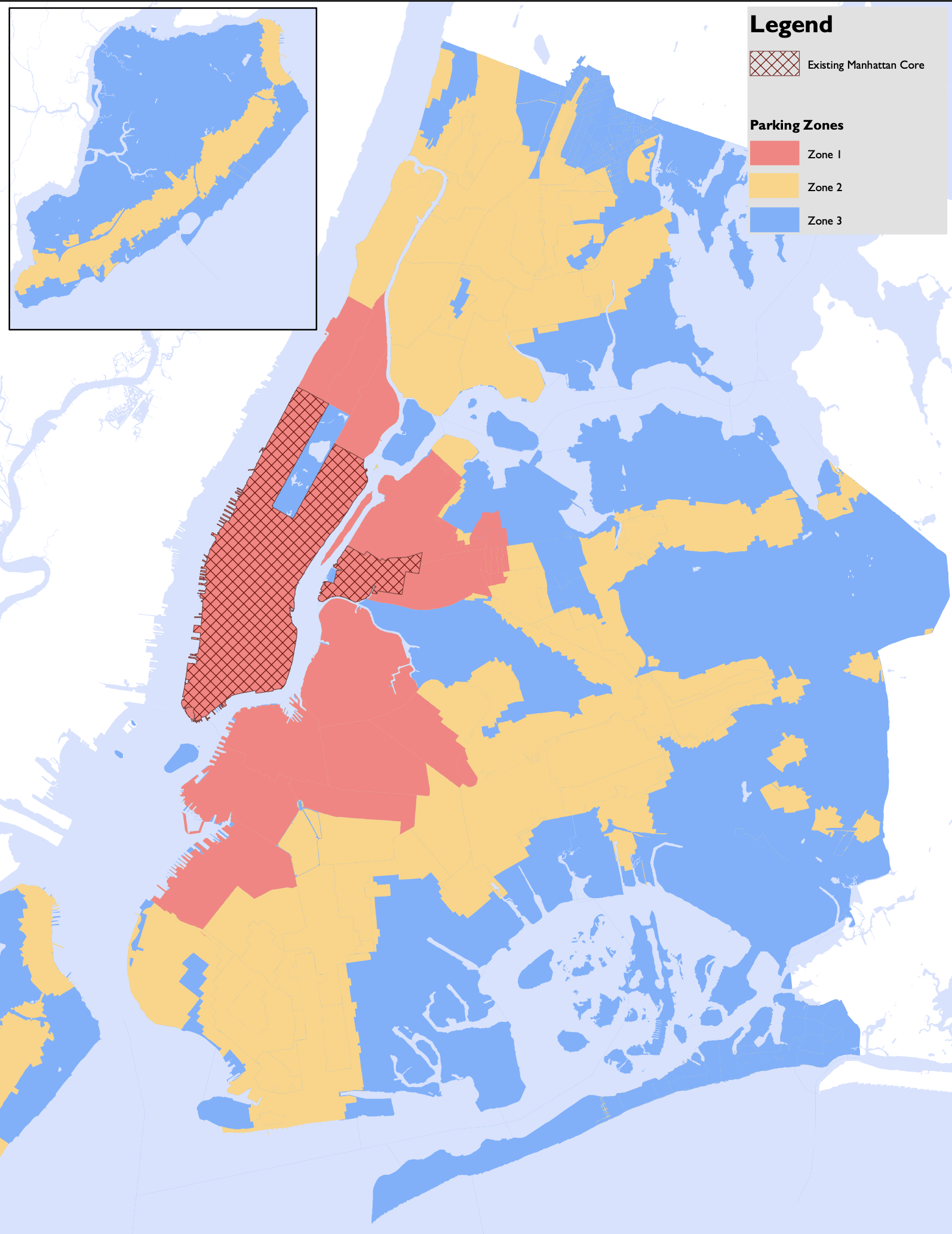

The City of Yes will leave most of Manhattan free of parking minimums and the northernmost parts of the borough with lower parking requirements for projects. They were also removed in the western parts of Brooklyn and Queens. In the rest of the city, the requirements were either reduced or left intact (much of Queens and Staten Island kept parking minimums).

Rick Gropper, founding principal of Camber Property Group, called the result a “huge benefit” for the city. It will have an immediate impact on his firm’s affordable housing projects: The scaled-back parking restrictions in parts of the Bronx significantly reduce how many spots his firm has to build at a large-scale development it is planning.

“Each space can add between $75,000 and $150,000 in cost to the job. It also adds complications, and affects the building design,” he said, noting that City of Yes will allow his firm to “do more with the same resources.”

Council member Kevin Riley, a Northeast Bronx resident who chairs the zoning subcommittee, defended the preservation of some parking mandates. He said planning should not be “theoretical or wishful thinking,” but reflect the “actual built environment” of neighborhoods.

“New York City is a very large city, and some areas of the city are not well serviced by public transportation. Is this fair? No. Should the residents in this badly serviced area be penalized further? No,” he said before the subcommittee’s vote. “I live in one of these areas. You need a car to get groceries, grab coffee or go to the doctor, bring your kids to the park. Our modifications reflect this reality, our constituents’ reality.”

The Universal Affordability Preference, which provides a 20 percent density bonus on projects that devote the extra space to affordable housing, was already seen as less developer-friendly than the program it is replacing, Voluntary Inclusionary Housing. UAP requires deeper affordability (units affordable for households earning, on average, 60 percent of the area median income) and provides less of a density bonus per square foot of affordable housing.

The Council changed that so when the density bonus is 10,000 square feet or more, at least 20 percent of the affordable units must be set aside for families earning 40 percent of the area median income. The change makes the program less appealing to developers.

The Council also added affordability requirements to “town center” and transit-oriented projects with 50 or more units, mandating 20 percent of units be set aside for those earning 80 percent of the AMI. The affordability rules could make projects financially infeasible for some developers, said Dan Marks, CEO of Brooklyn-based commercial brokerage TerraCRG.

“The proposal that they initially had would have had a much bigger impact than the proposal that is ultimately going to be passed,” he said. “My hope is that they didn’t take out so much that the impact is not going to be that great.”

Not cutting it

The administration estimates that the changes to City of Yes could add 80,000 housing units over the next 15 years, instead of the 109,000 originally projected beyond the usual production.

Some saw the modifications as an acquiescence to suburban opponents that came at too great a cost.

Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso criticized the exclusion of single-family, “contextual” zoning districts from the legalization of backyard accessory dwelling units. Transit-oriented development, which allows apartment buildings of three to five stories, was barred from areas zoned for single-family homes and duplexes.

“[City of Yes] was never a panacea for our city’s housing crisis,” Reynoso said in a statement. “But it was at least a modest opportunity to begin addressing the discriminatory zoning practices that force low-income, Black and Brown neighborhoods to do all of the work of building new housing while low-density neighborhoods get away with contributing nothing.”

Sara Lind, co-executive director of Open Plans, a group that advocates for ending parking mandates, called the outcome an “incremental victory.”

“We’re disappointed that it has once again proven so difficult for our leaders to stand boldly against car dominance, even as some Council members bemoan their districts’ lack of safe streets and transit options,” she said in a statement.

Staten Island Council member David Carr proposed a motion to reject the text amendment ahead of the zoning subcommittee’s vote.

“No to a process that solicited communities and community boards for their comments and feedback, only for it to be mostly ignored,” he said. “No to a process that tells hardworking residents what their neighborhoods should look like.”

The motion failed, but garnered support from Staten Island Council member Kamillah Hanks.

The final vote is slated for Dec. 5, and the text amendment’s on-the-ground impact will take time. Marks said the City of Yes completes a trifecta for the real estate industry this year, after passage of multifamily project tax break 485x and interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve.

“Those three things have shown people that New York City is open for business,” he said.

He noted that the mayor’s legal troubles raised concern that City of Yes would not advance, but its progress shows a recognition that “without bold policy changes, you are going to continue to have this housing crisis.”

“[Thursday] sort of proved that the need is bigger than any political trading that needs to happen here,” he said.

Read more