Presidents Herbert Hoover and John F. Kennedy once lived there, as did Secretary of State George Shultz. Now a lawsuit aims to open the exclusive Stanford University neighborhood to more housing.

The lawsuit, filed by a Stanford professor and a housing advocacy group, claims Santa Clara County broke state law after amending development standards for the university-owned Upper San Juan neighborhood, the San Jose Mercury News reported.

“If cities and counties can simply sidestep state law and prevent construction of housing, that’s just really bad for citizens around this entire state,” lawsuit plaintiff Ken Shotts, a tenured political economy professor who lives in an adjacent neighborhood, told the newspaper.

Shotts is suing the county along with the California Renters Legal Advocacy and Education Fund.

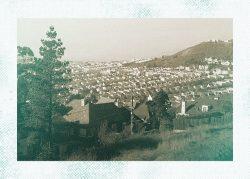

The historic neighborhood has 123 single-family homes that mostly house senior university faculty and some of their widows, who retain their houses for life.

But battle lines have been drawn between old-time residents who want to preserve the 130-year-old neighborhood and those sounding alarms over soaring housing costs and a lack of development.

Upper San Juan and its nearby neighborhoods were formed after the university was established in 1885, with the goal of having faculty and staff live on campus. The neighborhood’s historic homes, many over a century old and much larger than those in the surrounding area, are leased by residents while Stanford owns the land beneath them.

To help preserve the character of the neighborhood, county supervisors last spring unanimously voted to change the minimum distance homes must be set back from the street to 30 feet, from 25 feet. They also created standards for how much of a lot can be covered by a house to 20 percent for single-family homes and at 35 percent for multi-family homes.

The move came after Stanford promised to try to alleviate the faculty housing shortage. The Cabrillo-Dolores Faculty Homes, set to be completed next year, replaced two unoccupied single-family homes with seven new ones.

Some Upper San Juan residents claimed the new homes didn’t fit into the historic neighborhood.

Plaintiffs in the case argue that the supervisors’ changes violate Senate Bill 330, which was passed in 2019 to help prevent local governments from instituting new laws that do “anything that would lessen the intensity of housing.”

County officials insist that they haven’t made it any harder to build in Upper San Juan and are legally in the clear.

Todd Williams, an East Bay-based housing attorney, said that the county supervisors’ changes probably fall into a legal gray zone. The county didn’t outright change the zoning of Upper San Juan but changed rules on the edges that a judge may determine make housing more difficult.

“There is a real tension right now with what the state legislature is trying to do to address the housing crisis and local governments maintaining their discretion over local land use policy,” said Williams. “This is an area of the law that has not previously been tested.”

— Dana Bartholomew

Read more