Bay Area developers have filed nearly three dozen “builder’s remedy” projects to get around local zoning in 11 cities and counties to build more than 6,400 homes.

The growing number of jumbo-size projects filed under a “nuclear option” embedded under state housing law affects some of the region’s wealthiest cities, the San Jose Mercury News reported.

The projects include eight-story condo buildings towering over the billionaire bedroom community of Los Altos Hills, hundreds of apartments hugging single-family subdivisions of Brentwood, and 150 homes hovering on a bucolic hillside in rural Marin County.

Many of the proposals aim to build in upscale areas that long opposed large housing projects.

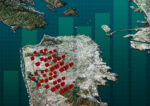

This year, they include at least 34 builder’s remedy projects with more than 6,400 units across 11 local cities and counties, according to a Bay Area News Group survey of local officials and planning documents throughout the region.

The builder’s remedy, a decades-old legal provision of the 1990 state Housing Accountability Act, was all but forgotten until last year. It serves as a penalty for cities that fail to meet their state-mandated housing goal deadline, allowing developers to bypass local zoning if they include enough affordable housing.

The untested legal tactic was first employed last year in Redondo Beach and Santa Monica in Southern California, as covered by The Real Deal, with ramifications for the Bay Area.

When the state passed the builder’s remedy rule, it was envisioned as a “nuclear option” to spur cities to follow through on their housing responsibilities, said Matt Regan, a housing policy expert with the pro-business Bay Area Council, which helped draft the law.

Fed up with red tape in the local permitting process, some developers now see it as a prime opportunity. “Those nuclear buttons are being pushed,” Regan told the Mercury News.

Of the Bay Area builder’s remedy projects, 15 are proposed in San Jose, five in Mountain View, three in Palo Alto, three in Los Altos Hills and two in Brentwood, plus a project each in Menlo Park, San Mateo, Pleasanton, Sonoma, Fairfax and Marin County.

One reason developers with such proposals target wealthy cities is they can charge higher rents and sale prices to offset the cost of affordable units.

Any city without a state-approved plan must accept a builder’s remedy project, advocates and developers say, as long as at least 20 percent of the units are affordable. Local governments in the Bay Area had until Jan. 31 to get approval for their “housing element” plans.

Four months later, just 28 of the 109 cities and counties in the region have had state regulators sign off on their eight-year plans, which would boost Bay Area housing stock by 15 percent. Cities are pushing back against builder’s remedy applications.

Los Altos Hills has indicated it could argue that an earlier version of its plan was in “substantial compliance” with state law, and therefore would be free to deny them. Other cities and towns — including San Mateo, Menlo Park, Atherton, Woodside, Lafayette, Concord and Pleasanton — have suggested they could deny builder’s remedy proposals regardless of state approval of their plans.The state’s Housing and Community Development Department this month issued a letter that could effectively undercut their arguments and bolster the legal durability of the controversial provision.

— Dana Bartholomew

Read more