From the day architect Cass Calder Smith received his master’s degree from UC Berkeley, he’s been a West Coast institution. His clean lines and experience-focused designs have produced some of San Francisco and Los Angeles’ most successful spaces.

But over the last decade, Smith and his New York Studio have also established him as the New York architect and designer on everything from modern homes to refined restaurants in Manhattan, the Hamptons and beyond. His commissions include residences in Soho, Greenwich Village and the Time Warner Center, shops in the World Trade Center’s Westfield Mall and Hudson Yards and the Ammirati offices in Union Square.

Seaport Food Hall – Tin Building

Most recently, his firm has been working with the Howard Hughes Corporation in the South Street Seaport district to design the SJP for Sarah Jessica Parker boutique. It is the interior architect of record on the 50,000-square-foot, three-story Jean-Georges food hall at the South Street Seaport’s landmark Tin Building, which is being reconstructed. With his depth of experience, Smith has become a trusted collaborator.

“Everyone on the Jean-Georges food hall project has very high expectations,” he says. “It’s a complex, multimillion-dollar project, and we have to make sure all the pieces fit together. But we are skilled at renovating buildings and inserting dining and drinking establishments into them.”

Retail – Tesla in LA

Smith’s firm is the design architect for projects of every kind on the West Coast, including the first-ever Tesla showroom in Los Angeles. In Manhattan, he’s behind numerous beloved restaurants — including Sarabeth’s in Chelsea Market and on Park Avenue South, as well as owner Sarabeth Levine’s home in Water Mill, Covina and O Ya in Nomad, and recently the historic Vesuvio Bakery in Soho. He’s built restaurant alliances in the Hamptons, where he and his team created Coche in Amagansett and Townline BBQ in Wainscott and renovated the famed Nick & Toni’s. With 10 houses on the South Fork under his belt, he enjoys working with a diverse range of clients on private and commercial projects, which he refers to as “art and commerce.”

But despite maintaining a staff of 25 spread between San Francisco and 180 Varick in New York, Smith long maintained the strongest association with the West Coast — until now.

“Iconic New York projects like the Tin Building are a sort of a homecoming for me,” says Smith. “People always ask me, ‘What’s the difference between the East and West Coast?’ For a designer, the West Coast is where a lot of creativity happens today — as does New York, but New York is still where lots of it is consumed. “

Indeed, Smith grew up in Greenwich Village — the son of Village Voice journalist and Academy Award-winning filmmaker Howard Smith — before a family split took him, his brother and his mother out West.

Fish Cove – Southampton, NY

“My parents were very bohemian,” says Smith, who discovered architectural drafting in high school. “I was always around people who were making things. In the 1970s, as a 12-year old, we moved to an 1,800-acre, off-the-grid commune at an old lumber mill in Woodside, California, that overlooked the jaw-dropping Pacific Ocean — officially called Star Hill Academy for Anything. There was a lot of old lumber just lying around, large logs and old machinery. Many interesting and creative people built these unique outlaw houses, and I unofficially apprenticed for them. They were everything: tree forts, earth-bermed lookouts, A-frames, log cabins and modified vehicles. No one had electricity or plumbing. I lived in an abandoned VW bus that I converted into a bedroom, and soon after helped my mom build a very small house out of old windows with solar passive heating, a wood-burning stove and a sleeping loft. It was formative in developing my interest in architecture and the process of how things are made.”

Springs Residence – East Hampton, NY

Even before graduating from architecture school at Berkeley — a place he says was “an inspiring magnet of creativity” and where his love for midcentury giants like Mies van der Rohe, Oscar Niemeyer, Richard Neutra and Le Corbusier began — Smith had already developed a following of residential clients in affluent Bay Area communities. They were small projects, but they allowed him to found his firm straight out of university.

“I was always pretty entrepreneurial, had developed respectable architectural and carpentry skills, and I worked my ass off,” he says. “The whole time I was in architecture school I was also doing ‘design-build,’ which was a popular alternative to traditional practice at the time. So, when I graduated, I already had experience and clients.”

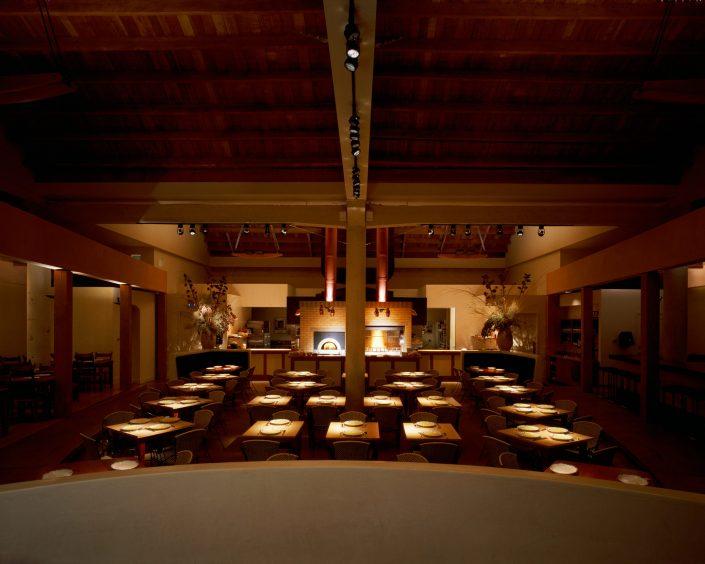

But it was a restaurant, not a residence, that put Smith on the national scene. In 1993, Restaurant LuLu opened in San Francisco’s South of Market neighborhood. It was Smith’s first-ever restaurant project, which also involved a large and complicated warehouse renovation.

Drawing on his European travels and life-long love of food, Smith imagined a fire-lit Mediterranean piazza — a contemporary interpretation of the layout of Michelangelo’s Renaissance Piazza del Campidoglio in Rome dropped into modern San Francisco.

LuLu

It was “like a public setting of harmony and chaos for 300 people,” he says. “It was spacious open yet intimate, very modern yet warm.” LuLu was an early coup for casual-cool dining at a time when high-end still largely meant overly designed interiors that were formal experiences detached from peoples’ lifestyles. It had a 24-year run.

“LuLu was this huge smash hit,” Smith says. “I got so much work from it. People were coming up to me and saying, ‘I want a house like that,’ ‘I want an office like that,’ ‘I want a restaurant like that.’ My firm went from two people to 20, but I kept a very hands-on approach.”

Smith still spent a lot of his youth and early design career visiting his father and friends in New York. And even as he became one of the Bay Area’s most in-demand designers, he says, he never stopped “angling for a way to get back to architecture in New York.”

Lagoon House – Stinson Beach, CA

“I wanted to return to my roots and get inspired by the culture,” he says, noting that the move was made practical since he now had two business partners in the San Francisco office. “If I hadn’t had such great clients on the West Coast, I probably would have made the leap sooner. But eventually I said, ‘You know what, I can do this. I can open in New York.’”

In 2005, Smith made the jump. He opened his Hudson Square office with a staff of two that’s now grown to 10, including principal architect Taylor Lawson and senior associate Yvonne Choy. Aside from the office, he’s merged two condos in his native West Village. His California aesthetic proved particularly suitable in the Hamptons, where shingle-style has given way to contemporary, clean-lined, naturally lit houses made with natural materials and intended for indoor-outdoor living and that support people’s casual lifestyles.

His success allowed him to do the Grand Tour of bucket-list triumphs in architecture: private tours of Le Corbusier’s buildings, trips to Venice for the Biennale and sauntering through the saunas of Helsinki.

In truth, it’s a good time to be a “card-carrying modernist,” as Smith describes himself. Midcentury design has evolved and become mainstream and less dogmatic without losing its cool. But Smith credits his West Coast and now East Coast success to the enduring “New York sensibility” he has always brought to his architecture.

“I appreciate the fundamental principles of design, but I think if the rules are there, feel free to improvise … have no fear,” he says.

View Smith’s array of project designs at casscaldersmith.com. Want a project consultation? Call 212-274-1211 or email info@casscaldersmith.com anytime.