Over the years, businessman and developer Vincent Trapani often had occasion to drive past an abandoned power generation plant at 1600 Fifth Avenue in Bay Shore on Long Island. Closed in 1995, the property was an eyesore, all the while sitting on the county tax rolls, accumulating $6.5 million in delinquent taxes over 23 years.

That is, until 2018, when Trapani bought the 1.8-acre site for $343,000, courtesy of the Suffolk County Land Bank, a nonprofit entity created expressly to acquire and facilitate the rehabilitation of derelict properties, transfer them to responsible owners and, in the process, restore them to the tax rolls and productive use in the community. Today, Trapani is in the process of cleaning up the site, which contains metals and other contaminants. He plans to build a parking and storage facility for nearby businesses.

“It will help 60 to 70 small businesses, giving them storage and a place to park close by,” said Trapani. “It helps the area and the community.”

The Suffolk County Land Bank is one of the many land banks that are cropping up in the tri-state area to deal with thousands of derelict homes and abandoned, contaminated industrial and manufacturing sites.

Authorized in New York in 2011 and more recently in New Jersey and Connecticut, land banks are increasingly taking over abandoned and often tax-delinquent properties that deter development, invite crime and vandalism and depress the value of homes and businesses nearby. Many of them — especially residential parcels — are the detritus of the mortgage crisis of 2008 and the Great Recession that followed. Land banks provide expertise and serve as a flexible tool for local governments to deal with the blighted properties.

“There was no demand at all for these properties to be developed liability-free without incentives or some sort of funding from the state or municipalities,” said Ann Catino, an attorney and co-chair of Connecticut’s Brownfield Working Group, a group of experts tasked with making recommendations for remediating and developing contaminated sites. “They were languishing, destroying the centers of a lot of communities, including places that are ripe for infrastructure,” she said.

Still, the process takes money and can be long and complicated as land banks navigate the necessary legal byways and try to come up with solutions that deliver the greatest benefit to communities. It’s not always easy to establish priorities in cities and neighborhoods that have large swaths of problem properties, said experts.

“They are all dealing with finite resources,” said Elizabeth Zeldin, director of the Neighborhood Impact Program for Enterprise Community Partners a nonprofit housing organization that is administering the New York State Attorney General’s latest round of funding to New York land banks. “Do they focus on properties that are the easiest to turn around quickly? Or on those in the most distressed communities where one transformation won’t change the neighborhood but is very important?”

Legislation guiding land banks varies from state to state, and operating methods are equally unique from one land bank to the next, but they are typically nonprofit entities or government redevelopment agencies that work with counties and municipalities to acquire vacant, abandoned or foreclosed properties. They can vacate tax liens — which often exceed the market value of a property — and eliminate liabilities that are deterrents to rehabilitation by municipalities and private developers alike. Some land banks rehab or demolish properties themselves. Others turn those tasks over to private developers and community organizations. They receive grants and other funding from state, county, municipal and federal agencies, private foundations and, in some cases, a cut of the taxes on properties returned to the tax rolls. Some are forging new ground in the effort to raise money, such as the Suffolk County Land Bank, which has an agreement with the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) that gives the land bank a proportionate share of the revenues of properties remediated by DEC and sold through the land bank.

Not surprisingly, “other land banks in the state have asked us to share the memorandum of understanding that we have with the DEC,” said Sarah Lansdale, executive director of the Suffolk County Land Bank.

Local land banking’s rise

The tri-state area is relatively new to land banking, which got its start in the Midwest some 40 years ago. In New Jersey, Governor Phil Murphy signed legislation in early July that allows municipalities to enter into agreements with land banks to purchase and foreclose on tax liens and acquire, rehabilitate and lease or sell properties. Land banks in New Jersey must also maintain a database of land-banked properties in their jurisdictions — an important feature of the legislation that creates a readily available list for developers interested in acquiring properties.

In testimony supporting the legislation, Newark Mayor Ras Baraka noted that in Newark alone there are more than 1,000 vacant and abandoned properties “diminishing property values and blighting neighborhoods.”

Connecticut is also new to the land banking scene. In 2017, the state’s Department of Housing provided $5 million to seed the Hartford Land Bank, which launched this summer. Laura Settlemyer, director of blight remediation for the city of Hartford, said that the bank is starting with tax deed property sales and expects to have its first inventory soon. In June of this year, the legislature took land banking further, authorizing any municipality in the state to create a land bank.

The year 2017 also saw passage of legislation creating brownfield land banks to deal with the contaminated industrial and manufacturing sites that, for example, plague such river towns as Hartford, Waterbury, Bridgeport and New London, which were home to the mills and factories that powered the industrial revolution in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Brownfield land banks can take control of properties, clear titles and tax liens and conduct or facilitate remediation and marketing. The first out of the gate was the Connecticut Brownfield Land Bank, which operates statewide. The bank doesn’t have a dedicated funding stream, but earns fees, receives grants from nonprofits and other private sources and can seek local and state funding.

“Our [job] is to take sites that the market has passed by and need intervention,” said Arthur Bogen, president of the land bank. “Land banks absolve municipalities of the politically charged process of taking on abandoned, contaminated sites. It’s a complicated process to clear the liens, get liability relief from the state and get funding in place to make it work.”

One of the bank’s first transactions will be the sale of an abandoned, contaminated manufacturing site in Southington. Selected by the town council in a bidding process, local developer Mark Lovley will buy the property from the land bank for $1 after remedial work is completed. He’ll share the cleanup bill with the state, which has put up $400,000. He said that he expects to spend $150,000. Lovley plans to put up two office buildings and noted that he’s already seeing tenant interest. Without the Connecticut Brownfield Bank helping the process, Lovley said he probably would not have bid on the property.

“It’s an unbelievably tedious process,” he said. “We’ve been working on it for close to three years.” But if it goes well, he said, he will “look to do more in the future.”

Remediation in the Empire State

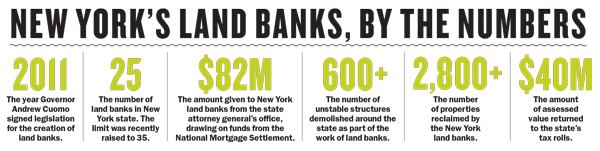

Compared to New Jersey and Connecticut, New York is an old hand at land banking, having eight years under its belt. Enabling legislation, signed by Governor Andrew Cuomo in 2011, has produced 25 land banks with the limit recently raised to 35. They have been funded over the years with $82 million from the state attorney general’s office, drawing on fines levied on financial institutions in the aftermath of the 2008 housing crisis. Most are county-level entities that, according to the New York Association of Land Banks, have reclaimed more than 2,800 properties around the state, conveying more than 1,200 of them to individuals or nonprofit organizations and returning $40 million of assessed value to the state’s tax rolls.

That should be good news in a state where the accumulation of blighted properties has reached a crisis level, said Adam Zaranko, president of the New York Land Bank Association and executive director of the Albany County Land Bank.

“Outside New York City, it’s probably one of the biggest challenges in the state,” said Zaranko. “Government hasn’t been able to solve in a systematic way for the most challenging properties, and the real estate market will rarely solve [problems] for these properties.”

The Albany County Land Bank has done more than 400 property sales, half of them to owner-occupants, Zaranko said. It’s now embarked on a more ambitious plan to assemble properties that can support development of multifamily and affordable housing.

A hundred miles south, the city of Newburgh, plagued by poverty and gang violence, has an estimated 700 abandoned homes. A number of the abandoned properties are within a 25-block area in its historic district that accounts for 3.4 percent of the city’s land but contains 25 percent of its vacant properties.

“In Newburgh, a lot of people walked away after the foreclosure crisis,” said Allison Cappella, the former executive director of the Newburgh Community Land Bank. “Newburgh has a very large historic district where the building stock is really old and really expensive and cost prohibitive to fix up.”

So far, the Newburgh Land Bank has acquired 119 properties, restored 74 to productive use and returned $4 million of assessment to the city’s tax rolls. It has used grant money in some cases to do lead and asbestos abatement and then transferred those properties to Habitat for Humanity, which turns them into affordable homes. The land bank is now partnering with a developer to rehab its first commercial site, creating four apartments in a three-story building and a restaurant on the ground floor.

The Suffolk County Land Bank, launched in 2013, is another active land bank in New York and one of a handful in the state that deals both with brownfield sites and with so-called zombie homes. It’s also unique in that it is staffed by county workers.

“We’re focused on areas that were hardest hit by the foreclosure crisis, in communities in Babylon, Brookhaven and Islip,” said Lansdale. Since 2013, Suffolk has had the highest foreclosure rate in the state, according to the state comptroller’s office.

Lansdale works with organizations such as the Long Island Community Development Corp. and the Long Island Housing Partnership, which rehabs properties and makes them available to first-time, income-qualified homebuyers. To date, it has sold 11 homes to first-time, income-qualified homebuyers and donated five to Habitat for Humanity. It has also managed the remediation, sale and development of eight brownfield properties, generating $1.7 million in revenue and $350,000 in annual taxes.

Next door in Nassau, the county land bank was launched in 2016. So far, it has acquired 11 properties and is currently in the process of selling its first property. But it sells only to developers and organizations that are willing and able to build affordable housing, said Brittney Russell, the executive director.

“We want to give people who never owned a home before the ability to own a home,” said Russell.