UPDATED: 12:29 p.m. November 25. For Vicki Gaily — co-owner and marketing director of the Special Properties Division of the northern New Jersey-based brokerage Brook Hollow Group — this year is shaping up to be far better than 2018.

Gaily’s firm, which is affiliated with Christie’s International Real Estate, has closed 45 residential deals at an average price of nearly $2 million so far this year, she said. That’s up from 37 deals for all of last year.

While many homebuyers had been holding back on purchases for a good chunk of the last 18 months as they agonized over the new federal cap on state and local tax — aka SALT — deductions, they’ve finally started transacting again.

“We are selling a lot of the higher-end homes that have been sitting for a long time,” said Gaily, whose territory includes the wealthy Bergen County towns of Saddle River, Upper Saddle River, Franklin Lakes and Mahwah.

Many in the suburban markets around New York City had been bracing for higher tax bills after the $10,000 cap on SALT deductions went into effect last year as part of President Donald Trump’s 2017 sweeping tax overhaul. Some were also anticipating a trickle-down effect that would hit local economies as financially squeezed homeowners put the brakes on spending at local stores, restaurants and other businesses.

The National Association of Realtors and others argued that the cap would virtually nullify the benefits homeowners had been reaping from the mortgage-interest deduction — a financial incentive widely touted as making buying residential property more attractive.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo went as far as calling the cap an act of “economic civil war” because it was handed down by a Republican White House and Congress and penalized heavily Democratic states most.

But many say concerns over how the changes to SALT would hurt residential sales were something of a self-fulfilling prophecy, causing buyers to hold off as they worried about their tax bills.

But many say concerns over how the changes to SALT would hurt residential sales were something of a self-fulfilling prophecy, causing buyers to hold off as they worried about their tax bills.

Brokers say, however, that buyers are now getting back into the game.

In addition to the fact that sellers have started lowering prices, part of the newfound ease comes from having a full tax year (and then some) on the books.

Many well-to-do homeowners, it turned out, couldn’t have received the full benefit of the SALT deductions anyway, since they would have been subject to the alternative minimum tax (AMT) — which limits or eliminates the SALT deduction.

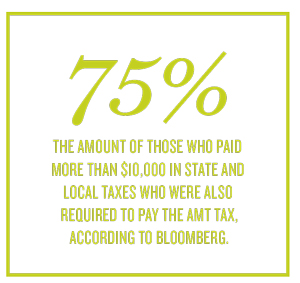

A recent Bloomberg analysis of IRS data from 10 of the wealthiest U.S. counties — including Westchester, Nassau, Fairfield, Bergen and Morris — estimated that nearly 75 percent of those who paid more than $10,000 in state and local taxes in previous years were required to pay the AMT. (And the good news for those who do get hit with the AMT is that it was also modified under the tax reform and is now less onerous and has higher income thresholds.)

While the tax code is clearly complicated, buyers have a better sense of how all of these changes are impacting their wallets. And that is at least creating more clarity over what they can spend.

“Buyers have digested the situation and are moving on,” said Angela Retelny, a Compass agent who specializes in properties in Scarsdale, Edgemont and other parts of southern Westchester. “Tax deductibility was a great factor in 2018, and the market stalled for a while until buyers understood the full impact and sellers realized that the market has changed.”

The under-$1M club

That’s not to say buyers — especially at the top of the market — are no longer wary of increased tax burdens.

One client who was recently looking at $2 million homes in Chappaqua ended up buying one for $1.5 million because he was concerned about taxes, said Douglas Elliman’s Nancy Strong, who also covers Westchester.

“Every deal is much harder,” she said. “Everyone is looking at the taxes, and everyone wants to pay less.”

But Strong said she expects more deals to close this year at $999,999, allowing homebuyers to at least dodge New York’s new mansion tax — a 1 percent levy on home sales starting at $1 million.

President Donald Trump’s tax overhaul had a lot of tri-state residents and brokers concerned.

In some cases, that’s more psychological than anything else. “If [buyers] can avoid the mansion tax, it makes them feel better,” Strong noted.

Real estate appraiser Jonathan Miller said sellers are pricing closer to the market than they have been in years. Additionally, the interest rate slide over the past year — the Federal Reserve has cut rates three times this year, most recently by a quarter of a point at the end of October — has been reinvigorating buyers in Westchester and Fairfield counties. That, he said, has mitigated much of the damage from SALT.

“The drop in interest rates is drawing out more buyers, and with sellers getting more realistic, it is such a powerful combination,” Miller said.

In the third quarter — post-income tax season — the number of sales was up 19.7 percent over the second quarter in Westchester and 10.5 percent in Fairfield, according to Elliman.

On Long Island, meanwhile, the North Shore of Nassau County saw sales jump 32 percent between the two quarters, Elliman found. And in Bergen County, sales of single-family homes were up 15.2 percent year-over-year in September, according to the New Jersey Realtors Association, which does not track sales on a quarterly basis.

Of course, some buyers are still flocking to income- and mansion-tax-free havens.

For ultrawealthy residents in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut — along with other high-tax states — the savings from living in a state like Florida are often enough of a reason to relocate, according to local agents. And the presence of the SALT deduction — even if it turned out to be less of an issue for some — was still, well, salt in the tax wound.

Bill Hernandez, an Elliman broker in Miami Beach, pointed to real estate bigwigs Barry Sternlicht, Michael Stern and Jamie LeFrak, who all purchased homes there this year. In early November, Trump joined them, changing his primary residence from Manhattan to Palm Beach.

“Look at the names coming down here,” said Hernandez, noting that his team has had “numerous conversations with clients who feel like they’re not being treated fairly” in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut.

“We’re taking hundreds of millions of dollars in tax revenue from those states,” he added.

Candace Adams, president and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway HomeServices New England, New York and Westchester Properties, echoed that sentiment.

“There’s a bit of a migration out of our states,” she told TRD in a recent interview. “There was already an exodus out because of the state taxes, the inheritance taxes … I think SALT was sort of the tipping point for a lot of people saying, ‘You know what? That’s it.’”

But Adams also noted that she’s seen some buyers who moved to Florida four or five years ago — before the changes to SALT, but because of high taxes in general — “boomerang” back to the tri-state. She attributed those reversals to “lifestyle — just missing the city.”

Salty buyers

While not as many were hurt by SALT as expected, there were homeowners in the metro area who felt pain.

In Westchester, average annual state and local taxes for big earners exceed $80,000, according to Bloomberg’s analysis. While Bloomberg found that 75 percent of those who paid $10,000-plus in state and local taxes were required to paid the AMT, that still leaves 25 percent who were not. And those homeowners are undoubtedly feeling the pinch, given that they still pay SALT and were likely deducting more than the $10,000 they’re now allotted.

In addition, Trump’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act lowered the allowable mortgage and home-equity interest deduction to $750,000, down from $1 million, initially putting a further damper on sales in high tax suburbs around New York.

From left: Vicky Gaily, Angela Retelny and Scott Elwell

And buyers, of course, look at these changes in their totality.

Syracuse University tax expert Leonard Burman said those who pay the AMT or are affected by the SALT cap “don’t have a tax incentive to get a more expensive house.”

“Ultimately, the way people decide about home ownership is by looking at their budget, seeing that they are paying $2,000 less in taxes and [therefore] can afford more than they could before,” said Burman, who is the chair of behavioral economics at Syracuse’s Maxwell School and a co-founder of the nonpartisan Tax Policy Institute think tank.

And buyers did, indeed, start changing their behavior as soon as the tax reform went into effect at the start of 2018.

In 2018’s first quarter, residential sales in Westchester were down 7.3 percent year-over-year. That worsened to a nearly 18 percent decline in the second quarter, according to Elliman. In Fairfield, meanwhile, sales were down 3.4 percent and 7.4 percent, respectively, in the same periods.

While it’s generally impossible to point to one single reason for the way an entire market moves, those drops extended into early 2019 before sales started picking up. Brokers say that’s because many were waiting to see what their tax returns would reveal.

But even as many of the counties in the tri-state area have seen an uptick in sales volume, brokers say SALT is still a big topic among clients. And that may be because everyone is searching for answers when properties don’t sell.

Elliman’s Strong said some homeowners are still micromanaging listings and “want to believe everything but price is the reason a house isn’t selling.”

The migration situation

In certain Bergen County areas like Old Tappan, Coldwell Banker agent Paula Clark said, there’s less concern about SALT — especially when a buyer’s local tax bill is below $25,000.

In fact, said Clark, “we’re still getting bidding wars in some markets.”

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo called the SALT cap an “economic civil war.”

Hoboken-based Jill Biggs, also a Coldwell agent, said she’s seeing less of an impact on sales from SALT than she is from new limits on H-1B visas. Those caps affect foreign workers who often buy closer to Manhattan, in Hoboken and Jersey City.

“They stopped buying and re-signed their leases,” said Biggs. “If they are not going to be able to stay in the country, they are not going to spend money [to buy a house].”

Up in Westchester, meanwhile, some homeowners are even migrating across the state line, seeking relief from SALT caps — a boon to some sellers (and brokers) in lower Fairfield, despite the taxes there. Greenwich broker Leslie McElwreath of Sotheby’s International Realty said she’s seen a boost in business from people fleeing higher-tax towns.

“It has actually helped us in Greenwich, because we have very low taxes,” said McElwreath. “We have really benefited.”

Alexander Chingas, of the boutique brokerage Riverside Realty Group in Westport, Connecticut, said he’s also seeing buyers moving into the area to lower their tax load.

“I wouldn’t call it an exodus,” he said. “But I can attribute a handful of sales directly to people who decided to move here from Westchester because the $10,000 deductible cap goes a little bit further.”

Chingas said 2019 is finishing stronger than it started, as sellers have become savvier about the market and pricing has adjusted to levels where buyers can find value. “[Sellers] know that if they want to make something happen, they have to be more realistic,” he said.

Scott Elwell, Elliman’s regional vice president of sales for Westchester and New England, said that “we’re seeing a lot of older inventory pass through now.”

“At all price points, including the higher end, sellers are coming to better terms of what a house is worth, and buyers are getting a better grasp on what they are willing to spend,” he said.

Brokers said buyers started stepping up shortly after they found out what the damage was from their 2018 tax bills.

“When buyers met with their accountants, it was almost like a faucet went on,” said Deborah Doern, regional vice president for Houlihan Lawrence in Westchester.

“They knew how it affected them or didn’t affect them — and moved accordingly,” she added. “Once that time passed, the number of sales went way up.”