Free rent. Paid attorneys’ fees. Falling prices. It sounds like a scary flashback to the dark days of 2009. But it’s actually all happening today in different segments of New York’s residential market.

After a multi-year run-up marked by prices that seemed to be on a never-ending upward trajectory, the tables have started to turn. Now, at least in many cases, it’s the buyers and renters who are holding the cards.

“A year ago, it was, ‘If you want to see my property, you’re going to need an appointment,’” said Joshua Silverbush, research director for the Marketing Directors, which specializes in new development brokerage. “Now we’re getting invitations.”

Both condo developers and landlords are sweetening the pot by throwing in concessions to woo buyers, tenants and brokers.

“That tells you right there that the market is challenged,” said Jonathan Miller [TRDataCustom], CEO of the appraisal firm Miller Samuel.

Although certain pockets of the residential market are trending upward — brokers are reporting bidding wars in the tight “affordable luxury” condo space, for example — there are broad sectors where buyers and renters have newfound leverage.

To be sure, it’s not 2009 again. In the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis, buyers were coming in with offers 20 to 40 percent below asking prices and demanding that developers return their deposits and release them from contracts.

But brokers say buyers’ markets in New York City are few and far between.

“I can count on one hand how many times,” the market has tipped to buyers, said Douglas Elliman broker Jacky Teplitzky. Her advice: “If you are a buyer in this market, I would definitely buy now.”

Below is a look at some of the key factors influencing today’s market and how those realities are changing the balance of power.

A surging supply

Inventory is beginning to pile up — at least in two key segments.

Indeed, both new development condos in Manhattan and rentals and Downtown Brooklyn are flooding the market.

In Manhattan, new development inventory surged 27 percent to a total 973 units on the market in 2016’s third quarter year-over-year after four quarters of decline, according to Miller Samuel data. And there could be five years of excess condo inventory sitting on the market by the end of 2017, an analysis released earlier this year by the appraisal firm found.

In Manhattan, new development inventory surged 27 percent to a total 973 units on the market in 2016’s third quarter year-over-year after four quarters of decline, according to Miller Samuel data. And there could be five years of excess condo inventory sitting on the market by the end of 2017, an analysis released earlier this year by the appraisal firm found.

That oversupply could spell trouble for the developers who are looking to unload condos quickly as concerns about softening in the market swirl.

“[It’s] causing a few things to happen,” said Peter Muoio, chief economist at the California-based property-auction website Ten-X, which does business in New York. “It’s allowing buyers more options and more time to decide what they want to buy [and it’s giving them] more to choose from. They’re not necessarily in as much of a rush.”

Sources say the surge can be at least partly attributed to the fact that skittish developers went overboard hoarding “shadow inventory” in early 2015 as the pace of sales started to slow.

As recently as Labor Day, there was a 67 percent year-over-year increase in Manhattan’s shadow inventory, bringing the number of shadow units up to 3,534, according to data from brokerage and analytics firm UrbanDigs.com. (By comparison, there were more than 6,000 actual Manhattan units listed.)

But sources say the shadow inventory trend is now reversing because developers have no choice but to put some of that inventory on the market.

Although keeping some units off the market can help make supply seem scarce and thus more desirable, those sponsors eventually have to start listing them, Miller said.

Meanwhile, the rental market is seeing its own supply glut.

In both Manhattan and Brooklyn, rental inventory ballooned by more than 30 percent in September, and in Queens it grew about 17 percent.

And the situation is expected to worsen in the coming months.

While total for-sale inventory in Brooklyn actually fell about 37 percent in the third quarter year-over-year, that borough is about to see the shoe drop on the rental side.

In Downtown Brooklyn alone, there are 23 residential buildings either recently completed or under construction that will add 7,500 apartments (mostly rentals) to the market by 2017. That’s roughly one-fifth of the rental units expected to come online citywide.

Buildings like the Stahl Organization’s 378-unit 388 Bridge Street, which is a mix of condos and rentals, the Gotham Organization’s 586-unit 250 Ashland Place and 7 Dekalb — the first residential tower at the City Point complex — are all contributing to the flood of supply.

“There is some pressure that’s going to come with all these units on the market,” said Silverbush of the Marketing Directors. “The biggest change is the incentives being offered.”

“It’s not necessarily crazy for new development. It’s not shocking, but it’s more of an issue when you see it in a large number of properties,” he added.

An absorption slowdown

In addition to the influx of supply, it’s also taking longer to move units.

Investors only need to look to a handful of prime Lower Manhattan neighborhoods to see evidence of that, most notably on the high end of the market.

So far this year, condos in the $1 to $3 million range have remained on the market for 26 weeks, roughly the same amount of time they took to sell in 2014, according to an analysis done by Robert Dankner, the president of Flatiron-based brokerage Prime Manhattan Realty.

So far this year, condos in the $1 to $3 million range have remained on the market for 26 weeks, roughly the same amount of time they took to sell in 2014, according to an analysis done by Robert Dankner, the president of Flatiron-based brokerage Prime Manhattan Realty.

But the same cannot be said for high-priced condos — those ranging from $6 to $50 million. Those units are now lingering for 50 weeks, 36 percent longer than the 32 weeks that they were hanging around in 2014.

“For the higher-priced properties, you start to see a very noticeable increased period of time that these properties were on the market before being sold,” Dankner told The Real Deal.

In Manhattan overall, condos and co-ops spent 79 days on the market in the third quarter, up 8.2 percent from the same time in 2015, according to Miller Samuel. The absorption rate — which measures how many months it would take to sell all active listings — stood at just over six months. That’s within the range of normal, but it’s 37 percent longer than last year.

Meanwhile, in Brooklyn, residential listings spent 81 days on the market in the third quarter before selling, 26 more days than they did a year earlier.

Miller said the slower sales pace suggests that sellers have not been able to “aspirationally” push their prices higher.

Laura Amin, a sales broker with Halstead Property in Brooklyn, said sellers must accept that the new normal involves a “longer, more thoughtful sale.”

“We prep them that the price might not automatically go up. It might actually come down a little bit,” she said. “It’s a little bit less of a feeding frenzy.”

On the rental side, Manhattan vacancies are on the rise. In September, 1.8 percent of available apartments were empty, according to the brokerage Citi Habitats. That was the highest vacancy rate since September 2009.

The incentives influx

With inventory up, the market is flush with developers and owners trying to entice buyers and renters to sign on the dotted line.

“The incentives are making and breaking deals when people are comparing apples to apples,” said Neeta Mulgaokar, a broker at Manhattan-based Mirador Real Estate.

Although the freebies that landlords are offering have remained flat — according to Miller Samuel, Manhattan landlords offered an average of 1.2 months in free rent both this (and last) September — the number of owners providing incentives is on the rise. Indeed, according to Citi Habitats, 28 percent of all landlords offered some type of concession in September — 10 percent higher than last year at the same time. The last time the level of concessions was that high was more than six years ago, in June 2010, when a flood of condos that had been converted to rentals hit the market.

This new reality is particularly overt in the rental market, where after a disappointing summer, landlords are trying to make up ground and end 2016 on a decent note.

Inducements like free rent (for anywhere between one and three months), paid broker fees and cash credits have been on the rise for about a year now.

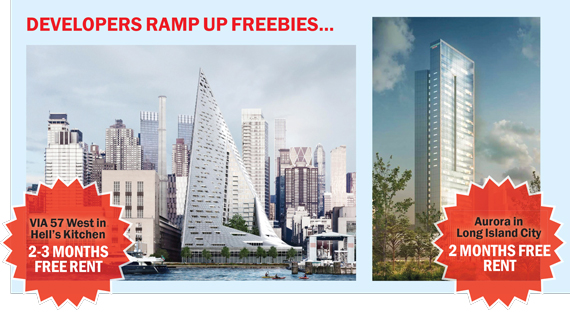

The Durst Organization, for example, has been offering two to three months of free rent and covering broker fees since March, when it launched leasing at its Bjarke Ingels-designed tetrahedron, dubbed VIA 57 West, in Hell’s Kitchen.

Rents in the 709-unit building start at $3,690 (for a studio) and go up to $16,000 (for a four-bedroom).

“In the last 24 months, there’s been a tremendous amount of construction,” Durst spokesperson Jordan Barowitz said. “There’s more supply on the market now than there was a year ago.”

He said offering concessions has allowed the company to “rent 30 to 35 apartments a month despite the inconvenience of living in an unfinished building that is an active job site.”

Meanwhile, G-Holdings is offering two free months at its 132-unit glassy Aurora tower at 29-11 Queens Plaza North in Long Island City. And the Moinian Group is offering a year of free amenities, including access to the building’s lap pool, to anyone who signs a two-year lease on a penthouse at its 71-story Sky apartment tower on the Far West Side. A spokesperson for the landlord said the firm just rented a penthouse for $25,000 a month.

And while incentives are often de rigueur for new developments, sources say there is increasing pressure on landlords to offer them at existing buildings.

“In the last few months, concessions have not just been limited to those [new] buildings,” Citi Habitats president Gary Malin told TRD. “You’re seeing them in buildings that wouldn’t necessarily qualify for them under normal, strong circumstances.”

“In the last few months, concessions have not just been limited to those [new] buildings,” Citi Habitats president Gary Malin told TRD. “You’re seeing them in buildings that wouldn’t necessarily qualify for them under normal, strong circumstances.”

At the 554-unit Gotham West on West 45th Street, completed in 2013, the Gotham Organization is offering $1,000 rent credits to anyone who signs a lease before Dec. 1. “If you don’t rent by mid-October or November, there’s a good chance you’ll be trying to rent in January,” Malin explained.

Representatives from G-Holdings declined to comment, while Gotham and Moinian did not return calls.

Smaller landlords are usually less prone to offer incentives because it takes a bigger bite out of their bottom lines. But even they are feeling pressure to dangle carrots.

At the 38-unit 115 Henry Street in Brooklyn Heights, landlord Novel Property Ventures is offering two months free rent on 18-month leases.

“We have a lot of apartments to lease,” Novel CEO Bennat Berger said in explaining the decision.

On the for-sale side, developers are reaching into their own bag of tricks to entice buyers, including offering free storage units or parking spaces.

And sources say some sponsors are offering to pay all or a portion of the buyer’s attorney fees and mortgage-recording tax, which can tack on around 1.6 percent of the unit’s cost to the final price tag.

That kind of savings can help get a deal across the finish line, especially at lower price points.

“Incentives are more favorable at the lower price points than higher price points,” said Andrew Barrocas, president of the residential brokerage MNS. “The closing cost on a $1 million apartment could be $50,000. Those out-of-pocket costs are watched more closely by the million-dollar buyer.”

The goal for sellers or landlords, of course, is to preserve the face value of their property — even if it means taking a slight financial haircut elsewhere. That’s largely because it allows them to maintain prices for the rest of their units. But these sweeteners, whether on the condo or rental side, are typically a precursor of what’s to come.

“It’s the first domino,” said Prime Manhattan Realty’s Dankner. “It usually ultimately leads to price breaks.”

Price reductions

When the pool of incentives dries up, some owners have no choice but to drop prices.

The top end of New York’s luxury market is seeing that now.

The trials and tribulations of developers along Billionaires’ Row are well documented. In September, TRD reported that an LLC owner at One57 went into contract for what was likely a substantial loss on a unit it purchased for $32 million in 2014. (Its final listing price was only $25 million.)

But if you look at just about any high-priced property, you’re likely to find pricing coming down.

“There’s definitely price-point resistance in general,” said Town Residential CEO Andrew Heiberger, noting that with the exception of a few prime properties, most of the high-end market is feeling the pressure.

Heiberger said he’s seeing this for properties priced “above $4,000 a square foot in some of the best buildings,” as well as in “very good buildings above $3,000 a foot” and for properties priced above $20 million.

On average, Manhattan condo and co-op listings were discounted only 2.9 percent in the third quarter from their last list price, according to Miller Samuel data. But a number of high-end properties are seeing far steeper chops.

At the Residences at Ritz Carlton at 50 Central Park South, for example, the owner of a 4,500-square-foot resale condo has lowered the ask every five months since it was first listed at $50 million in May 2015. After the most recent drop in July, the listing now stands at $35 million, a 30 percent discount.

In Brooklyn, a 3,208-square-foot Dumbo penthouse at 1 Main Street, which also hit the market in May 2015, trimmed about 15 percent off its original $8.8 million ask. In October, after a third price drop, it was listed at $7.5 million.

Brokers are quick to point out that the condo market is not a monolith and that some units —particularly in the lower price points — are seeing steady increases.

But sources say that as the top of the market cools, these price cuts are bound to trickle down.

Miller said the primary question he got as the condo pipeline was growing and owners began shaving prices was about “contagion.”

“Does this spill over to the lower price points? The answer is: eventually,” he said.

“It’s like a layer cake,” Miller added. “If the top is soft and offering a lot of concessions, it can melt into the next layer, so to speak.”

Rental prices are also dropping.

After Manhattan rent growth started to slow last summer, rents began falling earlier this year for the first time since 2014.

Manhattan median rents fell 1.2 percent in September year-over-year, to $3,396. Brooklyn rental prices, meanwhile, edged up 2.4 percent on the year, to $2,949, but that was after two consecutive months of declines.

And in Northwest Queens, the market has been mixed. Still, the median rental price for Long Island City, Astoria, Sunnyside and Woodside was down 5.7 percent on the year in September, to $2,787.

Wooing brokers

The fact that brokers are often the gatekeepers to buyers isn’t lost on owners looking to lease or sell units.

At the 597-unit Helena rental building at 601 West 57th Street, Durst is spreading the word to brokers that they can collect their fees within seven days of a signed lease.

At condos, some developers are also offering bigger commissions. Aby Rosen’s RFR Realty is offering 3.5 percent — rather than the standard 2.5 or 3 percent — at its Foster & Partners-designed 100 East 53rd Street. RFR confirmed its higher commission rate, but declined to comment.

And some are offering broker incentives across their entire portfolios.

That’s what Toll Brothers City Living is doing. The company — which is selling the 108-unit Pierhouse in Brooklyn Bridge Park and the Sutton in Turtle Bay, which has 113 units — is offering an extra 0.5 percent commission for every buyer a broker brings to one of its properties. It is giving brokers a 3 percent commission on the first deal, 3.5 percent on the second, and 4 percent on every deal after that. Prices in the portfolio start at $949,990 and run to more than $10 million.

“When you get to the price points that we’re talking about, you largely see buyers coming in with brokers,” said Toll Brothers president David Von Spreckelsen. “That’s how you’re getting into buildings. With the plethora of new construction out there, sometimes it can be daunting for buyers to keep track of all of these buildings. They really rely on brokers to point things out for them.”

Others questioned the effectiveness of those kinds of incentives.

MNS’s Barrocas said savvy brokers are wary of “gimmicky” incentives.

“It depends on what the reasoning is,” he said. “Are they offering an additional brokerage fee because they undercut you at first and now they’re trying to make nice?”

It’s when the incentives start to get out of hand, he said, that you know sellers are really starting to feel the heat. “Things like that are a sign that the end is near,” he said.