For tenants and landlords in Los Angeles, the deadline is finally here: Three years and five months after the beginning of the pandemic, and eight months after the city’s Covid emergency order expired, starting on Tuesday landlords can legally bring eviction proceedings against tenants who owe back rent.

The deadline applies to rent that was due from March 2020 until October 2021, and comes as a large chunk of L.A.’s economy is shut down because of the Hollywood writers’ and actors’ strikes. And with hundreds of millions of dollars owed to landlords, for days the looming deadline has generated a citywide stir over a potential new wave of evictions, prompting frantic support efforts from city officials, panic among tenants and relief among some landlords.

“I am very worried about the deadline,” L.A. Mayor Karen Bass told the website LAist last week. “I’m concerned that we’re going to have another spike in homelessness.”

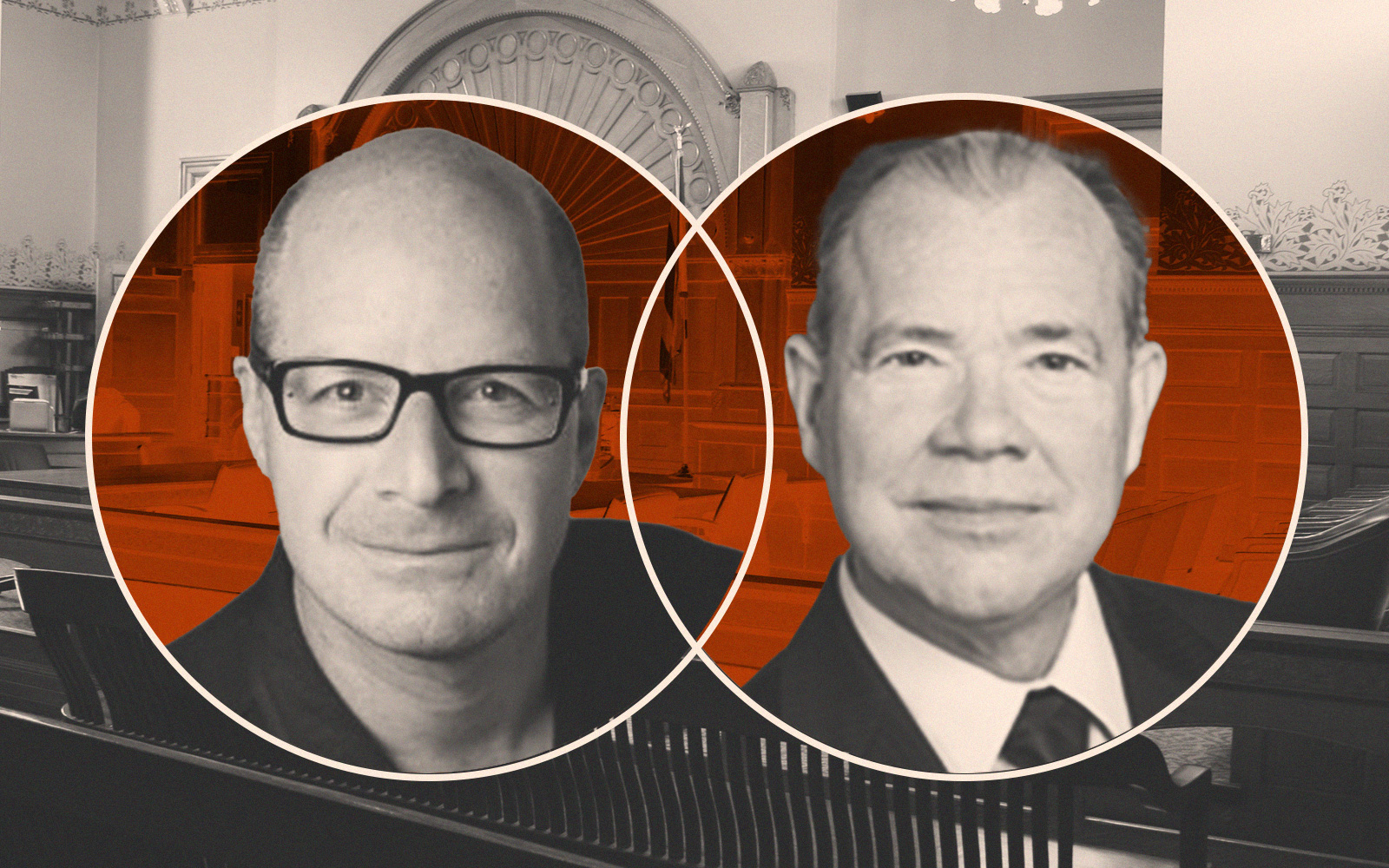

“The city needs to stop babysitting renters — it’s ridiculous,” countered Dan Yukelson, the executive director of the landlord advocacy group Apartment Association of Greater Los Angeles, in comments to TRD. “It wasn’t our fault that the government decided to shut down the economy.”

The deadline prompted a flurry of last-minute efforts from Bass and other officials to keep as many renters as possible in their homes. Last week, Bass and L.A. City Councilmember Nithya Raman detailed a proposal to use funding from Measure ULA — the city’s controversial new property transfer tax — for tenant assistance programs, including an $18.4 million short-term emergency fund for low-income tenants.

Advertising campaign

The mayor’s office and Los Angeles Housing Department also launched a public information campaign, with ads on social media, on foreign language radio stations and even on taco trucks that were directed at lower income city zip codes. On Monday, Bass and a small team of city officials continued the information blast with a joint press conference.

“We are working around the clock,” the mayor said in a statement, “to ensure that tenants know their rights, and that there are resources available to them in order to not self-evict. … We will continue to lock arms with our partners to solve this crisis so that everyone in Los Angeles has a safe place to sleep at night.”

The new ULA proposals amount to near $60 million in spending: In addition to the $18.4 million emergency fund, which would pay for up to six months of some tenants’ back rent, the plan also includes $23 million to expand an existing legal support program; $5.5 million for a tenant outreach and education program; and $11.2 million for a tenant harassment protection program.

To date, the controversial tax has raised $38 million, according to the city, although this year’s budget allocates $150 million from the measure. The city has said it will spend the money as it comes in, and reimburse the funds through grants if the tax gets overturned in court.

The City Council’s Housing and Homelessness Committee, chaired by Raman, was scheduled to vote on those programs on Tuesday and expected to pass them, which would send the efforts to the full council. Raman called the vote “an important step in reshaping the machinery of the city towards keeping people housed.”

But the proposed funding also pales in comparison to the debt owed by tenants: As of early May, in the city of L.A. alone an estimated 137,000 households owed a total of around $451 million, according to figures provided to TRD by researchers at PolicyLink, an Oakland-based research and economic and racial advocacy group.

“I think this data paints a picture of a deepening crisis — the affordability crisis that the city and California overall has been facing has been building up for decades,” said Jennifer Tran, director of the group’s National Equity Atlas.

The enormous gap means more evictions are likely inevitable, although it’s less clear how many.

In recent months new case filings around L.A. County have already been increasing as other pandemic-era moratorium laws have expired, and one prominent eviction attorney recently said he’ll have plenty of new cases “in the pipe to start on Aug. 2.”

Jasmine Rangel, a senior housing associate at PolicyLink, pointed to data that shows some 35,000 L.A. renters who applied to a state assistance program reported that they were facing eviction, and that the vast majority of the renters who are behind are people of color.

“So many people are behind on rent because of no fault of their own,” Rangel said. “They’re in jobs that were severely affected by the pandemic, their hours were cut, they lost their jobs.”

“Last resort”

But Yukelson pushed back against suggestions the new deadline will actually lead to a wave of forced displacement. Evictions are actually a “last resort” for property owners, he said, because in most cases the court proceedings drag on for months and wrack up expensive legal fees, all while the owner still has a tenant who’s not paying.

“So what happens in the real world is property owners have to put on their business hats and then negotiate a deal, and they end up paying bad actors who hadn’t paid their rent [for months] some money just to vacate their units,” he said.

Instead of celebrating the August deadline, the landlord advocate, who does support the $18 million short-term emergency fund proposal, was mostly looking toward another one: Early next year, when the second tranche of pandemic back rent comes due and the city’s rent hike freeze expires.

“These three years under these Covid regulations were about the worst thing that could ever have happened to someone who’s made their investment in rental property,” he said. “The fat lady doesn’t sing until February.”

Read more