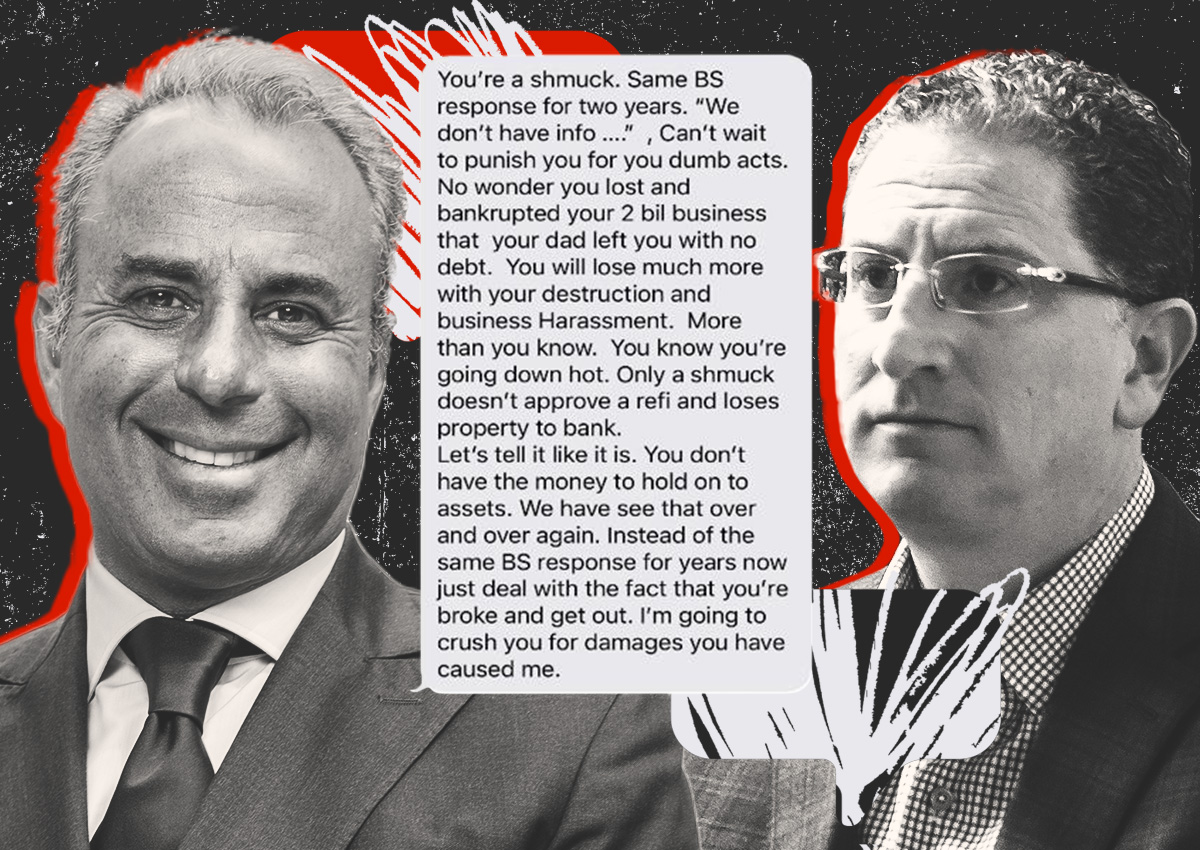

UPDATED, 1:15 p.m., October 5, 2023: The dispute between Ben Ashkenazy and the Gindi family is no closer to a resolution after nearly three years in the courts and a litany of threats from both sides, ranging from theft to the destruction of their businesses.

The Gindis have come out swinging with more accusations in a dozen exhibits and memos from lawyers Darren and Terrence Oved, adding another loop to a winding legal battle centered on a close-knit real estate community. The Gindis want to sanction Ashkenazy “for commencing this frivolous lawsuit and submitting a blatantly perjurious affidavit” and are asking the judge to award the defendants attorneys’ fees and expenses.

“This motion details how Ashkenazy allegedly perpetrated a high stakes scheme against trusting investors and now seeks to defraud the Court to further enrich himself at their expense,” their lawyers said.

The war between the partners began three years ago when Ashkenazy sued the Gindis in a Manhattan court for defaming him amongst prominent members of the Syrian-Jewish community and refusing to pay capital calls on properties they owned together. Ashkenazy Acquisition Corp. has dealt with foreclosures across its portfolio, some of which its founder blames on the Gindis, owners of Century 21, which went bankrupt in 2020 and closed 13 stores.

The Gindis fired back, alleging it was Ashkenazy who owed them money. Ashkenazy further threatened to “go nuclear” on them for destroying his business, according to the Gindis.

While the Manhattan case was grinding on, Ashkenazy went after the Gindis in Kings County early last year for a six-year-old default on a $10 million loan for a real estate investment, claiming the Gindis owed over $15 million with interest.

The Gindis now allege this loan was not a loan, but instead a placeholder to record distributions from a cash-out refinancing made years ago. The Oveds, their lawyers, say the latest lawsuit is a “desperate attempt to gain leverage” in the Manhattan case and is part of a “decade-long scheme to misappropriate millions of dollars from his investors.”

That’s “a continued false narrative,” according to an Ashkenazy Acquisition Corp. spokesperson. He said that more than 25 of 40 counterclaims brought by the Gindis were already thrown out in the original lawsuit.

“The Gindis’ allegations in their most recent attempt to avoid their monetary obligations to Ashkenazy are meritless,” said the spokesperson. “Ironically, it is the Gindis’ multi-billion, Century 21 empire that “crumbled” under their watch, having filed for bankruptcy a few years ago.”

Partners, then foes

The public feud is unusual in New York’s tight-knit Syrian-Jewish community where disputes are often settled outside of court.

Members within and outside the community have attempted to resolve it. Kushner Companies founder Charles Kushner, who is not involved in the dispute, offered to help mediate in late 2020.

“I know from personal experience that these fights have a life of their own and rarely end with a good conclusion,” wrote Kushner, who is famously estranged from his brother, Murray.

The issues in the Brooklyn lawsuit date back to 2008, according to the Gindis.

They claim they made a $25 million investment with Ashkenazy in an office building at 625 Madison Avenue, broken into a $15 million equity stake and a $10 million loan. The Gindis allege Ashkenazy granted them a put option, which required Ashkenazy to repurchase the equity interest and repay the loan.

But the Gindis allege Ashkenazy was unable to pay. The family says Ashkenazy granted them an equity interest in its Union Station project in Washington, D.C. instead of the $25 million. But the Gindis allege it never got the needed sign-offs from the Union Station Redevelopment Commission and their lender Wells Fargo. Their ownership stake was never recognized.

In 2014, Ashkenazy closed on a $275 million cash-out refinancing of Union Station. A year later, the distributions were documented with the $10 million placeholder note because Ashkenazy never got the appropriate sign-offs from the Union Station Redevelopment Commission and their lender, according to the Gindis’ court filing. Three years later, Ashkenazy secured another refinancing, but the Gindis allege the money went to pay down a mezzanine loan at 625 North Michigan Avenue in Chicago.

Ashkenazy has yet to respond to the most recent filings in court. Ashkenazy’s attorney in the Brooklyn lawsuit, Kevin Nash, previously said the Gindis are attempting to invent problems.

The Gindis have sought to move the Brooklyn case to Manhattan, but their request was denied. The judge also denied Ashkenazy’s motion for summary judgment, which would end the case, ruling the lender never signed the loan or provided a payment schedule. Ashkenazy is appealing the ruling.

Meanwhile, the Manhattan case is ongoing.

Endgame

Last year, New York judge Andrea Masley dismissed many of the counterclaims brought by the Gindis related to capital calls in a 132-page decision. Judge Masley allowed some claims to move forward and the Gindis then brought an additional 14 claims against Ashkenazy.

Ashkenazy’s lawyer in the New York case, Kevin Cyrulnik of Kasowitz Benson Torres, argued at a recent hearing in that case that the Gindis are just trying to delay.

“The Court should not allow the Gindis to drag this case down any longer,” said Cyrulnik. “It has been pending for three years. Ashkenazy has been trying to get his day in court.”

They argue that the Gindis have “starved properties of capital.” Their lawyer said they have already lost two Upper West Side properties: 1991 Broadway and 2067 Broadway.

“Now, I don’t know what the Gindis’ endgame was,” said Cyrulnik. “We think it was to force this buyout or to be able to buy out Ben [Ashkenazy].

The Gindis have requested financial information about their Ashkenazy investments for years, but he failed to provide it, according to the Gindis’ former attorney, Peter Sherwin of Proskauer Rose.

“My clients are the true plaintiffs in this action,” said Sherwin. He said he is waiting for depositions.

Masley also wants more information. She did not make a ruling on any of the claims at the June hearing.

“All of the documents that you all are putting before me right now show that you need discovery to get the full story for me,” said Judge Masley.

She noted a decision could take a while in a case that has dragged on for years already.

“It takes me so long to do decisions, and it’s not getting any better,” said Masley.

Correction: This story has been updated to clarify that the Gindis are asking to sanction Ashkenazy.

Read more