Kushner Companies’ record $1.8 billion acquisition of 666 Fifth Avenue in 2007, funded with $1.75 billion in debt, was a gamble the firm is still reeling from today. But thanks to a highly unusual appraisal, the deal didn’t look that risky on paper to the bond investors that ultimately funded it.

Appraisers valued the property’s office portion alone at $2 billion at the time of the acquisition, according to a bond prospectus reviewed by The Real Deal. That would make the entire tower worth up to $3 billion — or around 70 percent more than the record price Kushner paid, with no changes to the building’s fundamentals and within just two months of closing on the deal.

Industry sources say such a big gap between purchase price and appraisal is virtually unheard of. Why it came to be is a mystery. UBS and Barclays, who provided the financing, declined to comment. Kushner Companies did not respond to a request for comment. Several sources involved in or familiar with the financing claimed they do not recall who appraised the tower, and even to say that, they requested anonymity.

The 666 Fifth deal is now seen as emblematic of the heady, overleveraged plays made during the height of the market in 2007. Purchase prices were based largely on predictions of future income that assumed a dramatic increase in rents, while actual cash flows took a backseat. Much has been written about the property, which continues to be in the spotlight as special counsel Robert Mueller is looking into Jared Kushner’s finances. But the appraisal that enabled Kushner to borrow such a sum to begin with, a sum that became the firm’s albatross, hasn’t been examined until now.

The appraisal

In an October 2007 TRD story about the deal, Scott Latham recalled the Kushner entourage’s reaction to touring 666 Fifth.

“When love presents itself at first sight, it’s pretty apparent,” said Latham, who brokered the deal on behalf of seller Tishman Speyer. “You can see the chemistry working, you can tell it’s happening — just like when someone spots a woman across the bar.”

Kushner wanted to pre-empt the dog-and-pony show that selling a tower like this would usually entail. Latham referenced other big-ticket deals, to make it clear that he would have to come up with a big number.

A day later, Kushner came back with a one-page offer: $1.8 billion, a new record for a Manhattan office property.

“We thought it was a number that would get the seller’s attention,” Kushner said.

Kushner Companies agreed to put down a mere $50 million in equity, and borrowed the remaining $1.75 billion from UBS and Barclays.

The senior part of the financing was a $1.215 billion, 10-year mortgage, which GE Capital and Wachovia Bank packaged into commercial mortgage backed securities (CMBS) and sold to bond investors. The balance was $535 million in short-term mezzanine debt. The sale closed in January 2007.

At the time, Kushner Companies planned to split the property into office and retail condos and pay off the mezzanine debt by selling the latter.

The $1.215 billion CMBS loan, meanwhile, was underwritten solely based on the income and appraised value of the tower’s 1.45 million-square-foot office portion, according to the prospectus for one of the loan pieces. At the time, the office’s net operating income was $53.5 million per year, with the biggest tenants at the property paying rents in the $40s and $50s per square foot. But the appraiser underwrote an annual income of $118.6 million, presumably under the assumption that expiring office leases could be replaced at a much higher rent. The appraised value in the prospectus, dated March 1, 2007, is $2 billion. A footnote specifies that the number excludes the tower’s retail space, meaning that the office portion was appraised at a whopping $1,379 per square foot.

One source close to the deal suggested CBRE conducted the appraisal, but TRD was unable to confirm that. Representatives for CBRE declined to comment.

The $2 billion appraisal meant the CMBS loan covered 60.75 percent of the office’s supposed value. This assumes the loan could be paid back even if the value plummeted by more than a third. An assumption that proved to be wrong, as the market began to tumble and rents started falling across the city, hurting the Kushners’ plan to increase the building’s income.

In July 2008, Kushner Companies sold a 49-percent stake in the retail to Crown Acquisitions and Carlyle Group for $525 million and refinanced the mezzanine debt. Even after that deal, the company struggled with the building, and in December 2011, it was forced to bring in Vornado Realty Trust to rescue the property. Kushner Companies sold Vornado a 49.5-percent stake in the office tower, and also reached a deal with its lenders to rework its debt.

The mortgage was split into a $1.1 billion A-note and a $115 million B-note, according to Trepp. The B-note is referred to colloquially as a “hope note,” since it is only repaid if all goes according to plan. Bondholders had to stomach lowered interest payments (part of the interest would accrue, adding to the hope note’s balance) and an extension of the loan’s maturity from 2017 to 2019.

The 2011 deals allowed Kushner Companies to hold on to the property. But despite the maneuvering, it couldn’t make the building profitable. According to a recent Bloomberg investigation, the tower lost $10 million in 2015 and was on track to losing more in 2016. Over the years, ambitious plans to redevelop the property were devised and then scrapped. Recently, Kushner Companies tried to raise money for a condo and retail redevelopment at what critics said were pie-in-the-sky valuations. But the talks, with the likes of China’s Anbang Insurance Group, a South Korean sovereign wealth fund and a Qatari royal, fell apart.

In April, Trepp estimated that the office portion of the tower could be worth $1.35 billion, “well below the original $2 billion appraisal.” The same month, the New York Times, citing Vornado’s public filings, reported that accrued interest swelled the mortgage balance to $1.4 billion.

A stealth operation

Early 2007 was a crazy time in the real estate market and plenty of people were overly confident in property values. It wasn’t unusual to see appraisals that inflated the value of just-purchased properties. But even taking the exuberance of that era into consideration, the 666 Fifth appraisal stands out.

Judging from the $525 million sale of a 49-percent stake in the tower’s retail space in mid-2008, the retail portion may have been worth more than $1 billion when Kushner Companies bought the property in 2007. Appraising the office portion at $2 billion would make the entire building worth over $3 billion — or 67 percent more than the $1.8 billion Kushner actually paid for it. Even if one assumes a very low valuation for the retail — say $500 million — that would still be a gap of almost 40 percent.

A veteran real estate lending executive, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that acquisition-loan appraisals during the boom could sometimes come in 10 to 20 percent above the sales price. But he could not recall a case where the gap was nearly as large as at 666 Fifth.

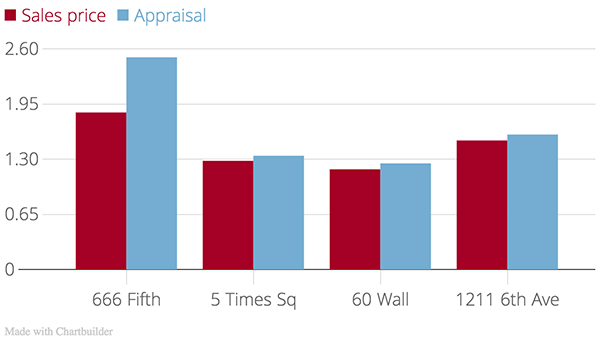

A chart showing the spread between the sales price and the appraised value (Credit: The Real Deal)

Publicly available data backs this up. The chart above compares sales price and appraised value for four Manhattan office towers that sold for over $1 billion between mid-2006 and mid-2007 and were financed with CMBS loans. (A bond rating agency shared the appraisal figures under the condition that its name not be mentioned.)

At three of the buildings — 60 Wall Street, 5 Times Square and 1211 Sixth Avenue — the acquisition-loan appraisal was between 4.6 and 5.9 percent higher than the sales price. At the fourth, 666 Fifth, the gap was 38.9 percent — and that’s assuming a very conservative retail valuation of $500 million. Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village was appraised at $5.4 billion in November 2006, according to Trepp, the month it sold to Tishman Speyer for $5.4 billion.

When executives involved in the sale or financing of the tower were presented with these findings, they either claimed not to remember who appraised the property or declined to talk altogether. Barclays and UBS declined to comment, with sources close to the banks citing client confidentiality.

Robert von Ancken, chair of Newmark Knight Frank Valuation & Advisory, said banking guidelines prohibit lenders from widely disclosing an appraiser’s identity, although the borrower typically knows. The idea, he said, is to make appraisers less susceptible to outside pressure: Banks typically choose the appraiser, but, in some cases, borrowers can choose one from a list provided by the bank, he added.

A CMBS expert at a major bond rating agency said that the appraisal document along with the identity of the appraiser is shared with the agencies rating the bonds. But these agencies typically don’t publicize it, the expert said.

Trepp’s Joe McBride said that rating agencies know the limitations and generally re-underwrite loans from scratch. “Appraisals are always taken with a grain of salt,” he said.

The flipside of all the secrecy is that bond investors and the general public don’t know who appraised a property and what kind of a relationship they have with the lender and borrower. It’s precisely this relationship that exacerbated the subprime mortgage crisis. Prosecutors charged several home appraisal firms with inflating property values during the boom years. In a 2007 survey, 90 percent of appraisers said they felt pressure from their clients to produce high valuations. “The bad appraisal,” Michael Sichenzi of Dynamic Consulting Services said at the time, “is probably 90 percent of the subprime problem.”