Little boxes on the hillside

Little boxes made of ticky tacky

Little boxes on the hillside

Little boxes all the same

The Malvina Reynolds song, immortalized in the opening credits of “Weeds,” is a dig at the numbing uniformity of suburbia’s single-family homes. One just like the next, interchangeable, generic. A commodity.

Veteran real estate investors, however, knew the truth: The single-family home was far from a commodity. Pricing was all over the place, as was quality. Tenants were wild cards, and home-level data was a cesspool. The inconsistency was so bad, in fact, that 15 million single-family rental properties collectively valued at nearly $4 trillion could hardly be considered an asset class.

A new generation of startups is taking that on. Those that have gained traction find themselves awash in capital, with the world’s biggest venture firms fighting to fund them. Roofstock, which raised $240 million in March at a $1.9 billion valuation, is the latest and perhaps most absorbing example.

Founded in 2015 by Gary Beasley, Gregor Watson, Devin Wade and Rich Ford, Roofstock is an online platform for single-family rentals. Individual investors can buy and sell homes that already have renters in place, with the company providing key metrics such as yield, annual return and home price appreciation.

Roofstock takes a 3 percent cut of the transaction price from sellers and a 0.5 percent fee from buyers. No brokers, no pre-purchase visits. Property management is offered as an add-on service. It’s passive real estate investment for the masses.

But also for the institutional classes.

Investors looking to buy and sell single-family rentals at scale have tapped in, trading hundreds of homes at a time. Figure out how much capital you want to deploy and where, and the algorithm does its thing, for a 1 percent cut.

Roofstock says that over $4 billion worth of deals have been done on its platform. Judging by its ecosystem-enriching bets and new products, its ambitions appear far larger.

Run by an alumnus of a behemoth that dominated the field in the mid-2010s, Roofstock wants to be the central nervous system for the sector, with the single-family rental looking and acting much more like a commodity.

But if the home does become a commodity, who ends up winning — and losing? The lion’s share of Roofstock’s business is institutional, and the company has created tools that make it easier for big investors to identify, buy and manage homes. As a result, it has to grapple with the growing concern that homeownership, long a mainstay of wealth creation for average Americans, is becoming more inaccessible thanks to institutional buyers. And that concern could trigger regulation.

Beasley, Roofstock’s CEO, disputes that narrative.

“We’re creating more liquidity and transparency and bringing down costs, which ultimately benefits investors of all sizes,” he said in an interview for this story.

Let’s break it down.

The action is the juice

Marketplaces live and die by volume. Facebook is worthless if the world’s not on it. The same goes for Uber, Airbnb and others that have built immense businesses by leveraging network effects: Every new user makes the platform more valuable for existing ones.

It’s no different for Roofstock. Activity is the company’s oxygen, and much of its war chest and resources have gone toward ensuring it.

Take Roofstock Academy. Launched in June 2019, it’s a repository of best practices for single-family investors, offering lectures, tutorials, coaching and networking. Membership is not free — the top tier costs $5,000 annually — but the initiative looks to be less about profit than about greasing the flywheel, creating an army of investors who trade through the platform.

The startup even hosts a podcast, “The Remote Real Estate Investor,” to that end. Recent episodes include “How we’d invest $50K, as a beginner and as an experienced investor” and “How to tap into your retirement accounts, penalty- and tax-free.”

“It takes time to build credibility,” Beasley said of the firm’s content initiatives. “What we’re trying to do is be relevant to people in whatever phase of the cycle they’re in.”

Beasley, describes the single-family rental sector as a “bond indexed for inflation with an equity kicker.” Investors collect a prescribed monthly return in the form of rent while benefiting from rising home prices. Beasley noted that most investors finance the bulk of their purchase with debt, making the return on equity even more attractive.

“If you have a home that just covers its costs over a five-year period but it goes up 3.5 percent a year and you have an 80 percent loan on it, you can get a 14 or 15 percent annualized return on that,” he said on the firm’s podcast.

Those initiatives may gin up demand, but Roofstock also has to ensure the platform offers enough homes for sale — an expensive challenge in such a frenzied housing market. In January, it announced it was investing more into iBuying, using its algorithms to price homes and purchase them in bulk. It’s a capital-intensive and risky game — just ask Zillow, which got out of it, and market leaders Opendoor and Offerpad, which continue to eat losses.

There are an awful lot of positives to institutional capital providing quality, affordable workforce housing for people who choose to rent.

Yet Beasley believes Roofstock’s preference for buying homes with tenants sets it apart.

“Every day we hold these homes, we make money. Every day a traditional iBuyer holds those homes, it costs them money,” he told The Real Deal. “We don’t have to turn out capital as quickly, and since we have such good insights into what investors are looking for, this really is in service of creating marketplace liquidity and putting products on the shelf that they want.”

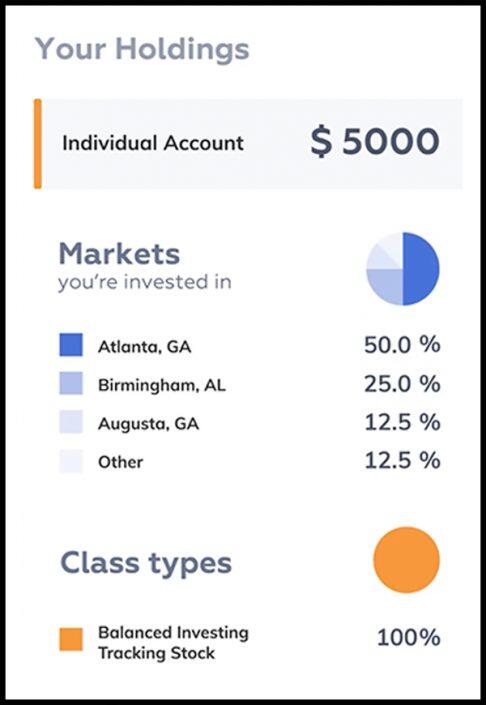

The company keeps pushing the boundaries of what it means to be a landlord. In November, it announced Roofstock One, a product for fractionalized ownership of homes, through which investors can buy stakes in single-family rentals. Rather than buy, say, two homes in a single market outright, you could buy shares in 20 homes across markets, spreading your risk.

A snapshot of the Roofstock One tool (Credit: Roofstock)

Investors can either buy common stock, which gives them stakes in all the properties in the program, or tracking stocks, which allow them to bet on a specific region or a home type — say, two-bed, two-baths in the mid-Atlantic. Though investors are expected to lock in their money for five years, that might change. Down the road, the company plans to commoditize it by creating a secondary market trading platform. Think day trading for pieces of single-family rentals.

It’s now exploring tokenizing ownership on the blockchain, which could speed up investments and create more deal flow. The digital ledger would hold granular information about each property, from previous sale and rental information to inspections, property upgrades and more.

In real estate investing, “there’s not a great secondary market,” Beasley said. Tokenization, he said, creates this “instant liquidity that eliminates that asymmetry of information between buyer and seller, which is always present in a real estate transaction.”

“The idea is to continue to make these shares more freely tradeable,” he added, “whether that’s on our own exchange or other exchanges, once it gets productized.”

Mailing it in

“So you want to be a landlord?” is a popular meme on real estate Twitter. Owners share war stories of how wrong things can go at their properties, ranging from boilers bursting at midnight to far more lurid tales.

So you want to be a landlord?

Finished an eviction against a prostitute and my began renovation. The workers had to remove the credit card reader she had mounted on the bedroom wall.

Surprises lurk at every corner.

— Marc Gilbert (@MarcSGilbert) December 7, 2021

It’s an illustration of how tricky it is to make real estate investing a passive activity — something that’s even more challenging if you don’t live nearby. Roofstock seems to grasp this, with much of its M&A activity focused on tackling this problem.

In March 2021, as part of an investment into the startup by commercial real estate giant JLL, Roofstock acquired Stessa, JLL’s single-family asset management software platform. The tool allows investors to automate income and expense tracking and helps with financial reporting and tax documentation.

Over the summer it acquired property-management firm Great Jones, and it has a preferred partner program with other property managers — think of it like Airbnb granting “superhost” status to hosts with consistently high ratings — as well as with providers of title insurance and escrow services.

“I look for someone that has enough scale, that has a long track record and as well [can] share data with me on how well they operate their properties,” co-founder Watson said on a company podcast about selecting preferred partners. “I want to know, if there’s a leak, do they have a plumber that they have pre-negotiated terms with, that it’s going to be lower than what I could get if I was managing this myself?”

Democratize or institutionalize?

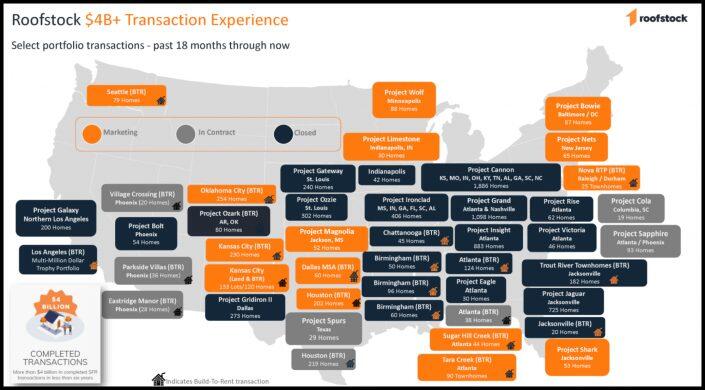

A snapshot of institutional transactions on Roofstock. Much activity has come from the built-to-rent sector. (Credit: Roofstock)

One of the most consequential trends in real estate investing is large investors’ increasingly insatiable appetite for single-family rentals. Historically high home prices have taken ownership off the table for many families, while pandemic-induced migration and millennials starting families have accelerated the demand for homes. Renting is often the only option, a self-fulfilling prophecy as single-family rental players bid up prices in select areas.

Homes built to rent were the top performer of the U.S. real estate market in 2021, with an average risk-adjusted annual return of 8 percent, according to Green Street data cited by the Wall Street Journal. Even traditional homebuilding giants such as Lennar and D.R. Horton have made significant bets in the space, gearing a lot of their new construction toward rentals rather than for-sale properties.

And then there are Wall Street players such as KKR, Invitation Homes and Blackstone doubling down. Construction of close to 100,000 built-to-rent homes kicked off in 2021, according to estimates, with investors pumping $30 billion into the sector. The number of built-to-rent homes increased 30 percent in 2020, according to the New York Times, and now make up about 6 percent of homes being built. That share is expected to double in the next decade.

With so much capital and excitement, the single-family rental sector has become a big focus for startups and venture capital. Companies that help these landlords identify, buy and operate homes have raised serious cash at hefty valuations. Lessen, which was co-founded by Roofstock’s Watson and connects landlords with contractors, pulled in $170 million at a $1 billion-plus valuation in November. Entera, which helps landlords streamline acquisitions, raised $32 million in July. And smart-home company SmartRent went public in a $2.2 billion SPAC deal last summer.

Roofstock is no slouch at fundraising, either: The company has garnered $365 million across eight rounds, according to CB Insights. Salesforce founder Marc Benioff was an angel investor, and SoftBank led its $240 million Series E round last month, with additional money from Bain Capital, Khosla Ventures and JLL’s proptech investment arm, JLL Spark.

According to CB Insights, Roofstock had a “down round” in January 2020, with its valuation dropping to $428 million from $550 million. Roofstock disputes this figure and claims it had a $600 million valuation at the time of that raise, though it didn’t disclose it then. What’s not in dispute is its rapid growth during the pandemic.

While institutional demand for single-family rentals practically guarantees deal flow for Roofstock, it raises questions about the evolution of the sector. Should wealth creation through real estate ownership and investing be for everyone, or will free-market mechanics stack the deck in favor of those who already have serious capital?

Make more single-family homes available to individuals, families, and nonprofit organizations rather than large investors.

“Isn’t that the case with any asset?” Beasley said in response. “Institutional investors bid up stocks, right? Are they crowding out the mom-and-pop investor because they’re buying equities? Maybe, maybe not.”

A look at Roofstock’s products shows its intent to deepen that institutional business. Its portfolio product functions like an investment-sales brokerage, combining tech with traditional property marketing. A recent snapshot of transactions from its website shows that the firm has sold large bundles of homes, including “Project Cannon,” an 1,886-home package spanning several states.

It also brokered the sale of several built-to-rent portfolios and has a partnership with Lennar that allows investors on the platform to buy new homes from the homebuilder and then help them operate them as rentals.

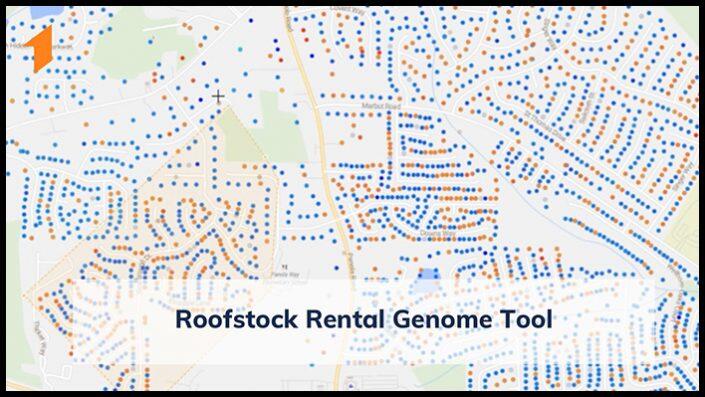

Then there’s the really heady stuff. Roofstock offers institutional buyers access to its “rental genome” tool, which claims to have mapped all 90 million single-family homes in the U.S. Investors can see which are owner-occupied and the gross rental yield, and can filter by criteria such as whether the home is in a tax-friendly Opportunity Zone.

The rental genome tool, which claims to have mapped out the entire single-family home stock of the U.S. (Credit: Roofstock)

“The fact that sellers don’t need to vacate the homes to sell them through Roofstock allows us to tap into the 16 million homes that are already rented and market them with tenants in place,” a voiceover in the video showcasing the genome tool says.

Beasley hails from the “Starwood mafia,” a group of executives at Barry Sternlicht’s Starwood Capital who went on to dominate the single-family rental and hospitality sectors in the 2010s. He was CEO of Waypoint Homes and then co-CEO of Starwood Waypoint Residential Trust, today a part of Invitation Homes.

Those behemoths have attracted a lot of media scrutiny, with major publications examining the impact of institutional ownership on the single-family sector.

With headlines such as “When Wall Street Is Your Landlord,” those articles have caught the attention of housing advocates and lawmakers.

The White House, in a September memo introducing the “Build Back Better” program, addressed concerns about growing institutional ownership.

“Large investor purchases of single-family homes and conversion into rental properties speeds the transition of neighborhoods from homeownership to rental and drives up home prices for lower-cost homes, making it harder for aspiring first-time and first-generation home buyers, among others, to buy a home,” a White House memo warned in September.

It pledged to limit large investors’ purchases of certain FHA-insured and HUD-owned properties, and to expand and create periods in which only government entities, owner-occupants and qualified nonprofits can bid on certain properties.

Roofstock is aware that such rhetoric could lead to policies that hamper its ambitions.

In December, Beasley penned a Forbes column titled, “Wall Street Isn’t the Reason for All the Problems In the Housing Market.” He cited Roofstock research showing that large landlords own just 450,000 of the roughly 20 million single-family rentals in the U.S. While he acknowledged that the slice of the pie had grown in the past decade, he stressed that it “represents less than 2.5 percent of all single-family rentals and less than 0.5 percent of all single-family homes.”

“There should be plenty of room for institutional investors, small mom-and-pop landlords and individuals who want to own their own homes,” he wrote. “I believe there are more constructive discussions to be had that focus on creating solutions to problems rather than laying blame for them.”

His argument, however, did not address how pronounced institutional ownership can be in certain markets. In Atlanta, nearly a third of homes sold in the fourth quarter went to investors, according to an analysis by Redfin, with Charlotte, Jacksonville and Las Vegas not far behind.

In the interview with TRD, Beasley noted that Roofstock is actively involved in influencing how regulators treat the single-family sector.

“We’re involved with conversations at the state, local and national levels to try to educate folks about this,” he said. “There are a lot of policymakers who will listen to all sorts of arguments, even though they might not talk publicly about things. But people will listen.”