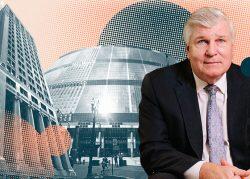

There’s little middle ground among Chicago residents and architecture critics on the James R. Thompson Center, which Google bought for $105 million as developer Mike Reschke revamps the spaceship-shaped building in the next three years. Passerby on Randolph and LaSalle Streets either love it or hate it.

The 37-year-old, 1.2-million-square-foot conical building was designed by the late Helmut Jahn, who created an open interior atrium as a symbol of government transparency because it housed state offices.

Now Jahn’s only child, Evan Jahn, 43, is president of the eponymous architecture firm long helmed by his father, who died in a bicycle accident last year at 81. Shortly after his death, Reschke, whose interest in reviving the property helped persuade Google to fill the entire building, phoned the younger Jahn to ask for details about the building and ideas on how to reposition it.

Jahn, who isn’t an architect, soon accepted an invitation for his firm to lead the redesign of the building, whose single-paned glass walls offered poor insulation in summer and winter and costs $17 million a year to operate.

Even at the news conference to announce the Google purchase, some people were joking about how much state workers didn’t like the building, Jahn said in an interview. Yet the plans by Reschke’s Prime Group “dissolved a lot of those conversations and arguments against why the building was unfavorable,” he said.

Read on for more details from Jahn on how the property will be transformed, why it’s unlikely the 110-story tower addition proposed by his father five years ago will come to pass and how architectural firms are reacting to waning demand for office space. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How do you feel about going back into the Thompson Center and designing its repositioning after Helmut, your father, originally designed it, and what are you planning?

The building is going to be enhanced to a level and expectation of a 21st century office, in terms of its operating efficiency, its daylight and its ventilation. The facade obviously has to change, based off of present day energy codes. People see it as this big glass building, but because it’s a lot of mirrored glass and opaque panels, they fail to realize it’s only about 25 percent visible glass, aside from the atrium glass wall. Most offices nowadays are closer to 60 or 70 percent visible glass, and we will bring it closer to that.

But we’re very enthusiastic to reinvestigate the opportunities for the Thompson Center now almost 40 years later. Because the technology has evolved that allows the building to showcase its potential for experimentation of what an office building can embody, not just from a metaphorical stance but actually now that we’re in this post-pandemic office hybrid work routine, to have more open space, more relationship with the outside, more opportunities for fresh air and collaboration space. It’s undeniable that it’s an iconic building and its interconnectedness with the city is inseparable.

Are air rights associated with the property? Could the footprint be potentially expanded?

You would have to talk to the developer group about that. I don’t think anything is changing based on what’s been discussed. There have been a lot of ideas thrown around about putting a tower on the site. Those were very conceptual or pre-concept sort of ideas put out there.

Do you feel the market is shrinking the size and height of office buildings with demand from tenants for smaller workspaces that fit hybrid schedules, and fewer needing hundreds of thousands of square feet that could anchor a 50-story or taller building? How does that change what a design firm does?

As you saw with the Google announcement, the Chicago central business district is actually performing quite well and has a lot of velocity, and trajectory is quite promising. When you have a single deal that takes 10 percent of the vacancy off the market, it’s pretty amazing. It’s not to neglect the fact there is a lot of available space on the market. I’m not trying to say we know the market as intimately as the development profession, but it seems and I agree with the assessment that there is a lot of downsizing and shifting in the market. Offices aren’t necessarily leaving, but that’s creating in the aggregate a net addition of vacancy. There is still a high demand for people to want to be in urban environments, if we can keep them safe, which, overall, the safety of cities has increased dramatically since the 1990s.

Is it important to show what’s possible with the chance to redo a building for a tenant such as Google on a property that’s older and fell out of favor as new development took hold of the market?

They’re beyond a bellwether. They’re really almost setting a new precedent in how they’re defining the workplace, with their projects in multiple areas. They’re really trying to reconceptualize this 21st century hybrid work environment. What I think is consistent is Google is all about movement and the fluidity of being able to choose your space, being able to quickly go to other parts of the building to meet with another department or colleague and breaking down those barriers that used to be a maze of cubicles. What you see the hybrid workforce demanding is a lot of spaces that are analogous to the comfort of working in a personal space like home. There is this mobility throughout the day that helps people’s focus and creativity.

What’s important to have in relationships between architecture firms and the real estate developers they work for? What makes them successful?

It’s important to have a very transparent and dignified relationship with a client. A lot of trust allows for a lot of fluid and frank flow of conversation about design and expectations. Hallmarks of our practice have always been to have a very close relationship with our clients and listen to them, help inform and educate them, but in the end, they’re our client, and we listen. But at the same time they’re coming to us for our architectural perspective. It’s our duty to give them our perspective, but it always ends up being a collaboration between what our ideas and knowledge are, and what their vision is. I would be doing anyone in development a disservice if we didn’t propose and push for something that is greater than what initially is the expectation. Like many things in life, you think you can run a mile this fast, and then someone challenges you to run a little bit faster and you figure out you can. You’re always moving the bar.

Read more