Last August, Apollo Global Management co-founder Marc Rowan saw a potential steal.

Last August, Apollo Global Management co-founder Marc Rowan saw a potential steal.

The real estate investment trust juggernaut AR Capital had become embroiled in an ugly accounting scandal and Rowan’s private equity firm smelled opportunity.

AR Capital’s stock price was crashing and its high-profile founder, Nicholas Schorsch, was forced to resign.

Under those bleak circumstances, Rowan struck a $378 million deal to buy 60 percent of the firm. “We don’t get to buy something of this size for this price without some hair on it,” he told the Wall Street Journal at the time. “We’re trading perspiration for purchase price.”

The upside was clearly huge. It would have more than doubled Apollo’s real estate assets under management to $27 billion and given it control of a mostly Manhattan-based portfolio comprised of 23 properties and about 3.4 million square feet, including trophy buildings like the Viceroy Hotel and One Worldwide Plaza.

But it was not to be. In November, the two parties suddenly called off the sale. Some speculated that federal investigations into AR Capital’s activities had led to complications. While rumors were swirling that part of the deal could be revived, a spokesperson for Apollo told The Real Deal last month that the deal is dead.

Regardless, Apollo’s bid to buy AR Capital sent an important signal to the real estate world: The private equity giant is hungry to grow its holdings and become a bigger real estate player.

In New York, the firm has been a lender on several high-profile luxury condo developments, including Izak Senbahar’s 56 Leonard Street in Tribeca and the Billionaires’ Row supertower by JDS Development and Property Markets Group at 111 West 57th Street.

Its $325 million mezzanine loan last year for the construction of 111 West 57th Street marked the biggest — and perhaps riskiest — real estate credit deal ever in New York.

“As a firm, broadly, we still think there’s more to do in real estate,” Stuart Rothstein, COO of the company’s real estate group, told TRD during a sit-down interview in the firm’s Midtown office. “If there’s a way to add to the portfolio of products — either by creating them or buying them — we’re open to both. It’s not necessarily about having the biggest fund. It’s about having different buckets of capital that allow us to play in the broadest range of assets and increase our ability to get transactions done.”

Bite-size deals

Apollo’s founders — who worked together at Wall Street investment bank Drezel Burnham Lambert before its infamous collapse in 1990 — are a trio of billionaires.

In addition to Rowan, they include buyout king Leon Black and Joshua Harris, who owns stakes in the New Jersey Devils hockey team and the Philadelphia 76ers.

With $170 billion in total assets under management, Apollo is considered a behemoth buyout shop, regularly delivering 25 percent returns to private equity investors over the course of a fund. It manages controlling interests in companies such as Twinkies manufacturer Hostess and Norwegian Cruise Lines, among many others.

From left: Leon Black, Marc Rowan and Joshua Harris

But its $11.3 billion in real estate assets under management are a drop in the bucket compared with those of its top-tier competitors.

Blackstone, for example, has the largest real estate holdings for a private equity firm, valued at more than $100 billion. Last fall alone, Blackstone raised a $15.8 billion fund to invest in global real estate.

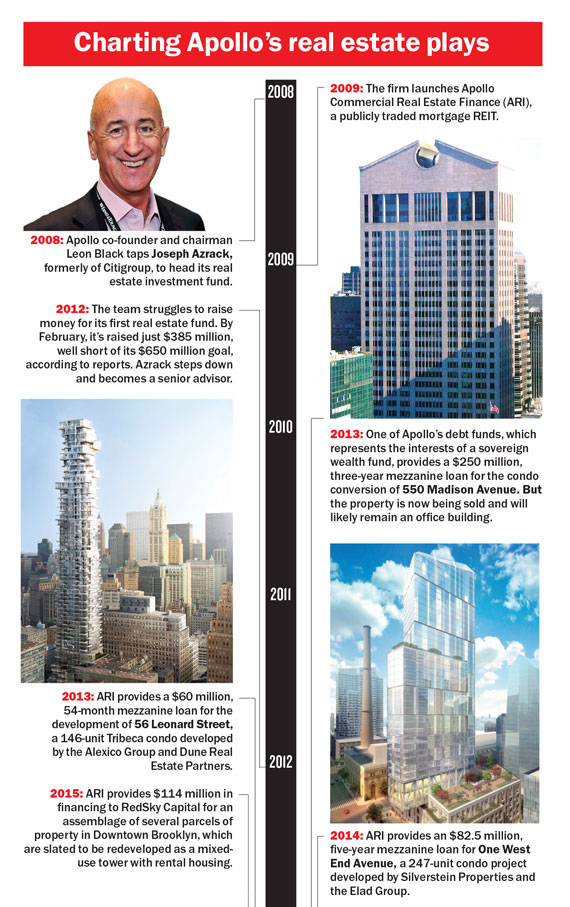

Apollo didn’t start a dedicated real estate investment vehicle until 2008, but it’s been gradually building its market share with bite-size deals on glitzy projects. Its average transaction loan size is about $50 million. “We’d like to be a lot bigger than we are,” said Harris, speaking about the real estate business on an October earnings call. “I’d say clearly, when you look at the size of our private equity business relative to, certainly, Blackstone but also a number of other players, there is a lot of room to grow.”

Its first New York condo transaction was a $60 million mezzanine loan in 2013 for the aforementioned 56 Leonard. The condo tower had been thrown into a tailspin by the financial crisis. Apollo followed Bank of America into the deal after the banking giant provided a massive $400 million construction loan to get the project back on track. The project was hardly a sure thing. It had been delayed nearly six years by the financial crisis and the national real estate firm Hines was brought in as a co-developer to jumpstart it.

“[The Apollo execs are] straight shooters,” said Senbahar, one of the project’s developers. “If they like a deal, they can move quickly and without a lot of red tape. That’s all you really need from a lender.”

The deal proved to be a home run for Apollo, which had a low basis and got its money out of the building last fall. As the firm looks to ramp up its deals, it is looking at 56 Leonard as a possible blueprint. “We’re trying to get paid for being a lender that’s willing to do the work and think outside the box with creative structuring and underwriting,” Rothstein said. “If all you want to do is put a 50 percent loan on a trophy office tower, you don’t need to come to me, and my capital is not going to be the cheapest.”

Similarly, Ben Bernstein, CEO of development firm RedSky, said Apollo is successfully filling a gap in the financing of complex, middle-market deals. “The banks are lower cost but are less interested in acquisition financing or bridge financing over 65 percent,” he said. “They’re looking for cleaner, simpler, cookie-cutter deals. For the more complex real estate, it’s not the most crowded space. Usually, we’re talking to the same five or six guys.”

‘Mutual fund’ model

Like the majority of private equity giants, Apollo’s cash is filtered through a slew of investment vehicles and independent funds.

On the real estate debt side, the firm invests through a REIT called Apollo Commercial Real Estate Finance, which trades on the New York Stock Exchange as ARI, as well as an Apollo-affiliated life insurance company Athene. It also invests on behalf of a large sovereign wealth fund widely rumored to be the Qatari Investment Authority. On the equity side, Apollo has raised a couple of dedicated funds to invest in real estate deals. Its two recent New York City deals include the purchase (and subsequent sale) of the Novotel New York Times Square.

On the real estate debt side, the firm invests through a REIT called Apollo Commercial Real Estate Finance, which trades on the New York Stock Exchange as ARI, as well as an Apollo-affiliated life insurance company Athene. It also invests on behalf of a large sovereign wealth fund widely rumored to be the Qatari Investment Authority. On the equity side, Apollo has raised a couple of dedicated funds to invest in real estate deals. Its two recent New York City deals include the purchase (and subsequent sale) of the Novotel New York Times Square.

For each of its debt issuance vehicles, the firm has different return expectations and appetites for risk. ARI goes after low double-digit returns for its investors, while the sovereign wealth fund it represents is satisfied with high single-figure returns. Meanwhile, Athene will settle for mid-single-digit returns in exchange for a lower investment risk profile.

Insiders said having such a diverse range of investment vehicles allows it to operate much like a mutual fund, smoothing out risk over a broad range of deals. The REIT, for example, has provided first-mortgage loans as well as riskier mezzanine financing that investors struggle to secure in choppy markets, making up a slice of the capital stack that traditional banks won’t fill.

In equity deals, where Apollo targets about 18 percent returns, the company has been significantly less active in New York City, citing the difficulty of generating cash flow from development. As a result, its equity deals here have been small but complicated transactions with high payoffs.

For example, in 2013 the company nabbed a Chinatown office building at 202 Canal Street for $41 million in partnership with Keystone Equities. Less than a week after buying the building it announced a lease to fill most of the property’s vacant office space, sold off the retail and turned the remaining office space into commercial condos, selling them individually for greater returns.

“We think it’s an all-weather strategy,” said Coburn Packard, the head of Apollo’s U.S. Real Estate Private Equity Group. “We are, by design, trying to avoid making a bet on the direction the market is headed.”

A risky move?

Contrary to its low profile on the equity side, Apollo took its debt business to a new level last year when it agreed to finance the construction of 111 West 57th. But in March, amid signs of a softening luxury market, the developers announced that they had opted to push back sales a year. Condos at the building are slated to be priced at upwards of $7,000 a foot, making them some of the most expensive ever sold in the city.

Insiders said that the delay has to be making lenders nervous.

Apollo execs, however, said the company still has confidence in the deal and claim its relatively low cost basis — $2,300 to $2,500 a foot — at the building will keep its investors’ money safe. “We feel we are well positioned at that basis,” Rothstein said. “Given our place in the capital structure, we’re not making the bet necessarily that there’s going to be a ton of condos sold at $7,000 and $8,000 a foot. But we do believe that we’re in a cyclical industry and that, at some point in time, someone will want to buy an apartment overlooking Central Park.”

In 2013, Apollo made a $250 million mezzanine loan at 550 Madison, also known as the Sony building, where the Chetrit Group and David Bistricer’s Clipper Equity had been seeking an office-to-condo conversion estimated to have a $1.8 billion sell-out. But in another sign of the shifting uber high-end condo market, the developers last month entered into a contract to sell the building to Olayan America, a division of Saudi conglomerate Olayan Group. According to sources, the purchase price was in excess of $1.3 billion. The new owners are said to be abandoning the condo plan.

While Apollo is focused on growth, it’s not blind to market realities. It has acknowledged that it’s slowing down its condo-lending binge in order to limit vulnerability. “We’re still open for business with condos but we have a pretty high bar considering our existing exposure,” Packard said.

The company wouldn’t say how close it is to its goal of raising $750 million in its latest real estate private equity fund. “It’s always difficult to raise money,” Rothstein said, adding that most institutions are still underexposed in real estate compared to other sectors.

Stephen Ellis, an analyst covering Apollo at investment research firm Morningstar, said that while Apollo’s attempt to buy AR Capital did not pan out, it might be best advised to buy a company rather than building its platform with one-off purchases.

“What they should be doing,” he said, “is thinking about an acquisition or two.”