Over the course of the last several years, billionaire Ken Griffin went on what can only be described as a real estate buying binge. There was a $60 million penthouse in Miami, a $59 million penthouse on Chicago’s Gold Coast and a $122 million mansion overlooking St. James’s Park in London. Then, for the hedge funder’s pièce de résistance, he closed on the record-breaking $238 million condo at 220 Central Park South.

Griffin obviously isn’t the first billionaire to purchase a second, third or fourth home in New York. And he has said he is in New York almost every week and plans to make this apartment his home in the city. But purchases like his — or at least those in the seven- and eight-figure price range — have become commonplace in Manhattan and have contributed to a much-maligned phenomenon here in which shiny new condo towers get sold out and then sit half empty for months at a time.

But Griffin’s 220 Central Park South deal put a new spotlight on this kind of investor activity, setting off last month’s scramble by state lawmakers to find a way to tax luxury residential purchases. That push was bolstered by ongoing concerns over money laundering and the sources of cash flowing into New York real estate through anonymous corporate entities.

Along the 57th Street corridor, clusters of so-called ghost towers — those with darkened apartments — can be spotted on any given night.

“These buildings were targeting the Billionaires’ Club of the world,” said attorney Pierre Debbas, the managing partner at the boutique real estate law firm Romer Debbas, who has a view of One Beacon Court from his Midtown office. “Most nights, there are five lights on. It’s crazy.”

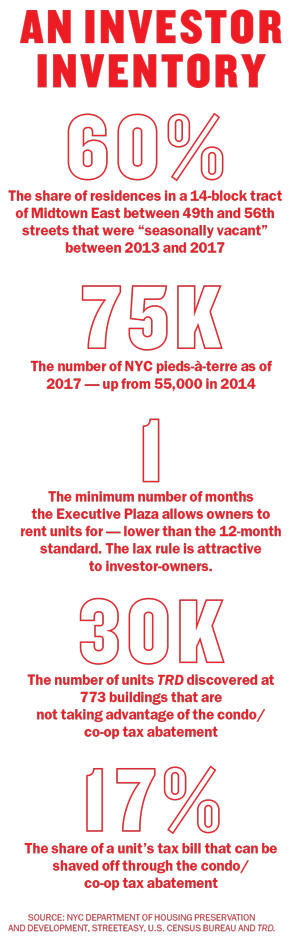

According to the latest U.S. Census Bureau data, 60 percent of residences in a 14-block tract of Midtown East between 49th and 56th streets were “seasonally vacant” between 2013 and 2017.

Meanwhile, a recent study by the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development found that the number of pieds-à-terre in the city jumped to 75,000 from 55,000 between 2014 and 2017. City Comptroller Scott Stringer’s office estimated that 5,400 of them are worth $5 million or more.

During those boom years between 2014 and 2017, foreign investors — particularly from Russia and China — snapped up trophy apartments that doubled as safety deposit boxes.

During those boom years between 2014 and 2017, foreign investors — particularly from Russia and China — snapped up trophy apartments that doubled as safety deposit boxes.

“Some of these buildings are half empty. Is that a big deal?” said George Doerre, a vice president at M&T Bank, which has financed condo projects in the city. “That’s the question we’ve been asking for four or five years.”

This month, with that question top of mind, The Real Deal attempted to quantify these investor purchases, surveying Department of Finance tax rolls for over 92,000 Manhattan condo units in 773 buildings — all the Manhattan condo buildings with 30 or more units.

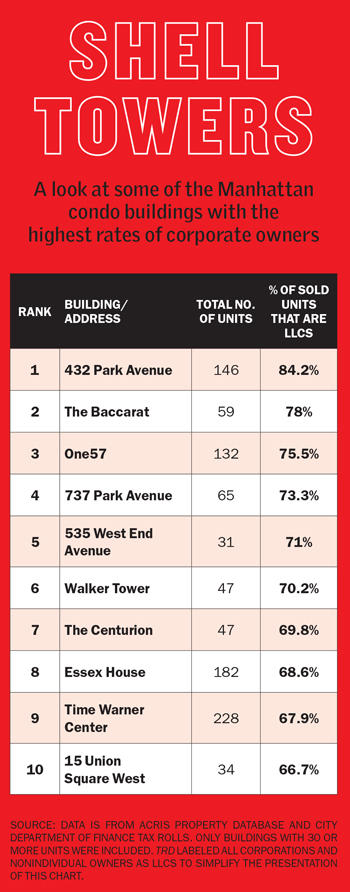

We found that roughly 16 percent — or about 15,000 of those units — were purchased through anonymous LLCs or other corporate entities. That figure offers some clues, because investors often use LLCs to buy apartments. The catch? So do many wealthy buyers who purchase their primary home through an LLC in order to protect their assets or maintain anonymity.

But there’s another key indicator of an apartment’s ownership status: An annual condo/co-op tax abatement available only on primary residences.

With help from the city’s Independent Budget Office — a nonpartisan organization that provides information about the city’s budget and tax revenue — we identified 30,000 units that didn’t claim this benefit, another sign of significant investor activity.

Related: Investors: A double-edged sword

That means around a third of the condos TRD surveyed are likely owned as pieds-à-terre or investor properties. And if you strip out other units from this equation that are ineligible for the abatement — for example, those getting another type of tax break— the percentage of pieds-à-terre or investor properties shoots up to 43 percent.

George Sweeting, deputy director for research at IBO, said the abundance of owners not receiving the tax break is notable.

“You would assume that these are relatively sophisticated owners, particularly at the high end,” Sweeting said. “I would assume that most co-op/condo owners in a building who are eligible for the abatement do apply for it. The benefit is fairly substantial.”

Though some would argue the benefit isn’t substantial enough to dissuade buyers from using LLCs, anecdotal evidence suggests investor units have piled up in certain corridors of the city.

Though some would argue the benefit isn’t substantial enough to dissuade buyers from using LLCs, anecdotal evidence suggests investor units have piled up in certain corridors of the city.

“You can just ride through my district at night, the East Side of Manhattan, and you’ll pass complete buildings where there are no lights on,” said U.S. Rep. Carolyn Maloney. “They’re bank accounts.”

A place to put your pillow

It’s no coincidence that pied-à-terre purchases are concentrated at the uppermost reaches of the market.

“It’s that level of success where you have the luxury of having your own pillow and artwork, so that when you’re in town you’re not in a hotel,” said Compass’ Vickey Barron, who has sold some of the priciest condos in the city.

Although geopolitical strife has slowed investment, brokers said pied-à-terre buyers have been largely immune to market fluctuations.

That’s because unlike investors who rent out their condos, returns are not the only motivation for this group.

“They’re not worried about tax breaks and jumbo mortgages or interest rates going up,” said Julie Perlin of Stribling & Associates, who specializes in pied-à-terre purchases in Midtown East.

According to sources, buildings like the Baccarat Hotel & Residences, 737 Park Avenue and 432 Park are heavy on units without primary residents.

TRD’s research seems to back that up.

For example, at 432 Park, where 114 of the 146 units had sold as of last month, just a handful of owners received the co-op/condo tax abatement in 2018 — although nearly 62 percent of owners are LLCs or other corporate entities that are not eligible for it.

At the nearby Plaza, the Corcoran Group’s Charlie Attias has sold 40 apartments over the past eight years. According to TRD’s analysis, all 164 sponsor units at the Plaza have sold, and the building has 97 LLCs/corporate owners and 39 units receiving the tax abatement.

“The majority are pieds-à-terre, and the majority are also foreign buyers,” Attias said, noting that they were drawn to the Plaza’s cachet and location.

Elliman’s Gail Sankarsingh said her buyers have been drawn to the Baccarat, where she sold the penthouse as a pied-à-terre for $42.5 million, for similar reasons.

Meanwhile, Asher Alcobi, a co-founder of Peter Ashe Realty, said he’s sold four condos at 432 Park — one to an investor who rented it out and three as pieds-à-terre.

“No one lives there full-time,” he said.

A spokesperson for Macklowe Properties and CIM Group, the developers of that property, declined to comment. (It should, however, be noted that they have sold the über-luxe building at a fast clip and unloaded a slew of headline-grabbing blockbuster properties).

Although Midtown has been a favorite location for investors and pied-à-terre owners, those buyers are increasingly looking Downtown.

At 56 Leonard, Brown Harris Stevens’ Sophie Ravet sold four pieds-à-terre. Elliman’s Madeline Hult Elghanayan said 160 Leroy, developed by hotelier Ian Schrager, has also attracted an international buyer pool.

“There were buyers from Australia, Hong Kong and Turkey,” she said. “There’s one person from the Upper East Side who wanted a Downtown apartment. I saw her in the elevator the other day — they live on the Upper East, and this is their weekend getaway.”

Pied-à-terre and investment properties are, of course, not exclusive to New York. A recent analysis by the international organization Global Witness found that 87,000 properties in England and Wales are owned by anonymous companies registered in tax havens.

But in New York, sources say, most developers anticipate that 10 to 15 percent of buyers are looking for an investment or pied-à-terre, and they plan amenities accordingly.

“You’re putting in things that investors would use if they use it as a part-time place — like business centers and lounges,” said Andy Gerringer, head of new business development at the Marketing Directors.

Zeckendorf Development’s 520 Park, for example, has a wine and cocktail lounge. Buyers in that building include vacuum mogul James Dyson, one of England’s largest private landholders, as well as Ultimate Fighting Championship co-founder Frank Fertitta, whose primary home is in Las Vegas.

Despite a flurry of closings at 520 Park in recent months, inventory in the broader luxury Manhattan market is piling up, discounts are widespread, and sales velocity has slowed. And some say investors (those making financial transactions rather than buying second homes for themselves) are reacting.

“Investors are ducking and covering right now. They’re hoping to ride the market until it comes back,” said Dylan Pichulik, CEO of XL Real Property Management, which manages luxury residential properties for absentee owners in New York.

Pichulik said that over the past six months, 10 of his sellers have pulled listings off the market. “Everyone came back and said, ‘Okay, let’s put a tenant back in place and we’ll try again in a couple of years,’” he said.

Even buyers looking for trophy apartments think prices in the city are still too high, said attorney Debbas, who represented the buyer of a $17 million unit at 520 Park.

In addition, he said, the dollar has gotten stronger, and foreign investors increasingly view the U.S. as less politically stable than they once did.

Fueling rentals

While many ultrawealthy buyers are happy to have their condos sit empty for long stretches, the vast majority of investors are not.

This year, Compass’ Marie-Claire Martineau sold four condos at the Sutton on First Avenue to Chinese investors — each of whom ponied up $2.5 million to $4 million in cash. Upon closing, the units immediately went up for rent, she said.

These units are all adding to the inventory in the rental market. At Extell Development’s One57, the owner of Unit 56B paid about $10 million in 2011 and has been renting it out for $25,000 per month for the last few years.

“He didn’t have a mortgage and the common charges are $5,000 with taxes, so he nets $250,000,” said Corcoran’s Attias, who recently listed the apartment for $7.9 million.

But most investors want units priced under $3 million that will rent out quickly — a fact that condo boards have responded to by offering flexible rental rules.

Executive Plaza on West 51st Street, for example, has a one-month minimum stay, compared to a typical 12-month lease. The Link, 1600 Broadway and the Orion all have six-month minimums.

“Investors come in with cash, they rent it out and maybe five, six or seven years later we sell it for a profit,” said Martineau.

At the Orion, which was also developed by Extell and is entirely sold out, a stunning 98.7 percent of units are either owned by corporate structures or by residents not getting the condo and co-op abatement. That was the highest percentage TRD found.

Of the 551 units at the building — located at 350 West 42nd Street — 92 are owned by LLCs or other corporate structures, and only seven owners received the abatement in 2018. That’s only 1.5 percent of noncorporate-owned units. Neither Extell nor representatives for the Orion’s management company responded to requests for comment.

In addition, the building received a 421a tax abatement — which made it ineligible for the condo and co-op abatement — until that expired in 2018. But at that point a number of owners began looking to sell. Last month, the Orion had 24 listings, a fact brokers said is more evidence of investors.

“Now that the tax abatements are gone and the market is not great, owners are getting out,” said Martineau.

The Manhattan market has, indeed, seen five consecutive quarters of sales declines. What’s more, the weak rental market has further dampened investor purchases, according to appraiser Jonathan Miller, who added that investors and second-home purchasers are the first to stop buying when the market turns. “They’re going to wait for better conditions,” he said.

The Modlin Group’s Adam Modlin said that back in 2014 and 2015, investors who went into contract for new condos at $2,500 a foot believed their units would be worth $4,000 by the time they closed. “If you buy today, are you going to be in the money? No,” he said. “The greater likelihood is that when the project is complete, the price will go down.”

Despite that, Modlin said, the investor market is not dead.

An investor who bought a $5 million condo but has to sell at a 20 percent discount may be able to purchase a $10 million property for a similar discount. In that scenario, the investor stands to net $2 million, he said.

BHS’ Ravet agreed, saying that she continues to see activity among investors. She said one of her clients, a Canadian investor looking to spend up to $4 million on a condo to rent out, has been unequivocal about striking while the iron is hot.

“I spoke to him last week and he said, ‘I don’t care where it is in the city, just find me the best deal. I just want to park that money,’” she said.

— Additional reporting by Kevin Sun

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the timeline on Ken Griffin’s string of residential real estate purchases, including for his Chicago apartment. The story has been updated to reflect the accurate closing dates. It’s also been updated to include a public statement Griffin made about the amount of time he will spend in his 220 Central Park South apartment.