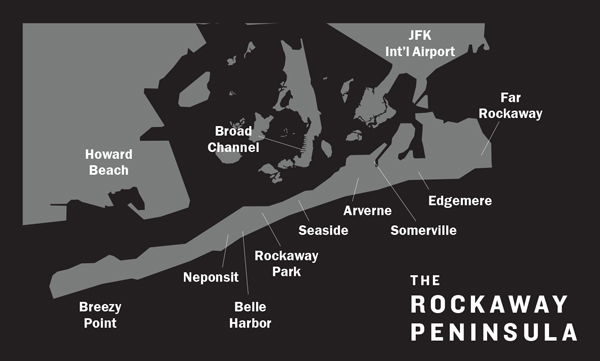

Rockaway — the roughly seven-square-mile peninsula nestled between Jamaica Bay and the Atlantic Ocean — has had a turbulent past. In the early 20th century, it was a seaside getaway, until new roads and train service made Long Island’s beaches easier to get to. By the middle of the century, many of the area’s quaint bungalows had been razed to make way for public housing under Robert Moses’ urban renewal program, while the area’s isolation from the rest of New York City has mainly left it an afterthought.

Rockaway — the roughly seven-square-mile peninsula nestled between Jamaica Bay and the Atlantic Ocean — has had a turbulent past. In the early 20th century, it was a seaside getaway, until new roads and train service made Long Island’s beaches easier to get to. By the middle of the century, many of the area’s quaint bungalows had been razed to make way for public housing under Robert Moses’ urban renewal program, while the area’s isolation from the rest of New York City has mainly left it an afterthought.

But the tide is finally turning. Major real estate firms, including Related Companies, JDS Development Group and the Marcal Group, have been busy building in the beach enclave. And a 23-block rezoning of Far Rockaway that was approved in September will inject an estimated $288 million in new investment and usher in more than 3,000 new residential units, leading local real estate players and others to predict that the community’s long-awaited boom is finally on its way.

“Every day, it seems like there’s another new developer coming in,” said City Council member Donovan Richards Jr., who represents the neighborhood. “I’ve been working in this community for 15 years, and I’ve never seen the amount of interest that we have seen lately.”

Rockaway already houses trendy locales such as Sayra’s Wine Bar on Rockaway Beach Boulevard and Beach 92nd Street, Epstein’s Beach bar two blocks east, and Rockaway Brewing Company at Failing Avenue and Beach 72nd Street. And there are more spots in the works.

“The beaches are magnificent. If you go there and see the nightlife, it became a hipster haven,” said Marcal Group founder and CEO Mark Caller, whose firm just broke ground on its $40 million, 24,000-square-foot mixed-use project at 147 Beach 116th Street, which will have 90 condo units in its first phase.

But these hip spots and new developments don’t change the fact that the peninsula is in a vulnerable spot. Hurricane Sandy ravaged the southernmost part of Queens in 2012, devastating the area’s homes and beaches. Residents were left without power for months after the storm hit, and a replacement for the boardwalk, which suffered extensive damage, wasn’t completed until this spring.

The developers that The Real Deal spoke to, however, didn’t seem too concerned about another major storm. They touted the city’s resiliency efforts and smart building as reasons not to worry.

“I think the fact that we survived Sandy was a good thing for the entire Rockaways,” said Gerard Romski, the project executive of Arverne by the Sea, which currently comprises 555 two-family homes and three mid-rise buildings. “Thankfully, Arverne demonstrated how, with good planning, you could build a sustainable oceanfront project and survive a couple hurricanes,” he added.

Slow change

Ron Moelis, head of L+M Development Partners, said he views the current wave of projects in Rockaway as a second chance for the neighborhood, which he argued has suffered from poor planning for decades.

“My impression is when Rockaway was heavily developed in the 1950s and ‘60s, it was done in a way that was not very thoughtful,” he said, noting that the neighborhood continued to be plagued by “underinvestment and lack of government focus up until the mid-2000s.”

L+M put its stamp on the neighborhood with its redevelopment of the sprawling rental property Arverne View. The company spent $232 million on the purchase and renovation of the Mitchell-Lama complex — consisting of 1,093 affordable units spread across 11 buildings — in November 2012, shortly after the development was flooded by Sandy.

L+M put its stamp on the neighborhood with its redevelopment of the sprawling rental property Arverne View. The company spent $232 million on the purchase and renovation of the Mitchell-Lama complex — consisting of 1,093 affordable units spread across 11 buildings — in November 2012, shortly after the development was flooded by Sandy.

But despite his company’s substantial investment in the area, Moelis said he is not yet completely sold on Rockaway. He noted that the peninsula still needs to become more self-sustainable — especially given how far away it is from virtually every other part of the city.

“It’s not an easy drive to Manhattan, so there need to be opportunities for people to do things locally,” he said, pointing to the lack of places to shop, eat, play and work.

This is part of what the recent Far Rockaway rezoning aims to remedy. Money from the city will go toward rebuilding the area’s commercial core, downtown Far Rockaway, as well as to several other projects meant to give the neighborhood a cultural boost. These include a new library branch at the corner of Central and Mott avenues and a $50,000 grant to the Queens Council for the Arts to support cultural organizations and events. Even prior to the rezoning, the city had issued a request for proposals for a roughly 42,500-square-foot site on Beach 21st Street, which it hopes to turn into a mixed-use, mixed-income development with affordable housing.

“I think this area could really use a face-lift to get people less afraid to invest,” said MDG Design + Construction CEO Matthew Rooney. In January, his firm inked a 99-year lease for the New York City Housing Authority’s Ocean Bay apartments on Beach 54th Street. MDG is undertaking a $560 million redevelopment of the 24-building, 1,395-unit complex.

“Having a project of this size, a redevelopment of this size, encourages outside investors,” Rooney said.

Jaime Schultz, a managing director at the retail and office brokerage Lee & Associates NYC and a Rockaway resident, said the area has already seen the early stages of a resurgence. And she even gave Hurricane Sandy some of the credit, maintaining that those who were not scared off by the superstorm became much less resistant to change in its wake.

Schultz pointed to the past three years as the period when Rockaway started to change in earnest, and said she’s seeing particularly strong interest from restaurant owners. But although that has been a welcome change, the area still needs to attract more major retailers, she noted.

The retail vacancy rate in Rockaway remains high, according to Council member Richards’ office. Not including the rundown Far Rockaway Shopping Center on Mott Avenue, a central site of the rezoning, the downtown area has a vacancy rate of 15 percent. By comparison, a Marcus & Millichap study found that the vacancy rates in Manhattan and Brooklyn were 3.8 percent and 2.9 percent, respectively, during 2017’s second quarter.

Schultz said that bringing more market-rate housing and retail to the area is key to turning the neighborhood around.

“No more 99-cent stores,” she said. “We want real retail, and we want market-rate apartments to elevate the quality of life.”

The litmus test

The Marcal Group’s Caller was prompted by the mayor’s office to check out Rockaway, he said. While riding a bike along Beach 116th Street about two years ago, he came across the site his company is now developing.

“I was like, this building has been sitting here for years,” he said. “Why hasn’t anyone done anything with it?”

The developer’s project will be finished in late 2019. Caller estimated that the condo units will go for between $500 and $600 per square foot and claimed to already have people who want to put down deposits.

Dan Wechsler, director of investment sales at Ariel Property Advisors, described the Marcal Group’s project as a “litmus test” for whether the neighborhood can support market-rate housing on a larger scale, since Rockaway has mostly attracted affordable- housing developments so far.

147 Beach 116th St.

Related Companies, for instance, is planning a 145-unit below-market-rate property just north of its Gateway Apartments project, which contains 364 affordable units in Downtown Far Rockaway. The Bluestone Organization also recently opened a 100-unit subsidized-housing project called Beach Green Dunes on Rockaway Beach Boulevard. And as a part of the rezoning, all the housing built on city-owned land will be affordable as well.

Affordability is part of the draw for potential residents, said Lisa Jackson, who owns the residential and commercial brokerage Rockaway Properties and has lived and worked in the area for more than 10 years.

The median rent in Rockaway was $1,850 as of June, according to StreetEasy. It has gradually risen over the past four years, hitting a peak of $1,950 in May 2016, but it’s still close to the bottom of rent prices in New York City. Other areas of Queens — Long Island City, Astoria and Ridgewood, for instance — all have median asking rents above $2,000.

One of the driving factors behind Rockaway’s relatively lower rents has been its lack of accessibility to Manhattan and Downtown Brooklyn, which can take up to an hour to get to by subway. The city has worked to provide alternatives, but those options haven’t cut down on the total commute time. In May, NYC launched ferry service between Beach 108th Street and Pier 11 at Wall Street. The roughly hour-long ferry ride also stops at 140 58th Street in Sunset Park.

Jackson noted that the new ferry, restaurants and boardwalk have helped lead to a spike in year-round activity. “The majority of people that come here for part-time living wind up making it longer than part-time,” she said.

Rockaway has seen a steady rise in sales of single- and two-family homes over the past few years, data from Ariel Property Advisors shows. Single-family home transactions more than doubled from 45 in 2012 to 96 in 2016, while two-family homes rose from 55 to 102 during the same period. Home values have gone up, too. Single-family home sales averaged $527,602 in 2017, up from about $430,000 in 2012, while the average for a two-family home rose to $409,289 from $361,000 in the same five-year span.

“The prices are significantly lower than Downtown Brooklyn and Manhattan,” Jackson said. “And it is a special neighborhood to live in.”

Building for a storm

New housing and retail could be a boon to Rockaway, but there are still reasons to be less than optimistic.

When Sandy hit, Rockaway’s beaches lost 1.5 million cubic yards. A fire that tore through the area burned down about 110 homes, and the city’s Build it Back program — which uses government funds to rebuild homes destroyed by the hurricane — was still working on reaching all participants late last month. In addition, a June report from the nonprofit Waterfront Alliance noted that 61 percent of Rockaway residents have a 50 percent chance of experiencing home flooding by 2060.

“Mother Nature always has the last vote, and the trend lines point in only one direction, which is higher sea level rise and fiercer storms,” said Roland Lewis, the organization’s president and CEO. “Any community or developer or anybody who’s building or thinking about doing anything in our coastal city should take heed.”

That’s not to say developers aren’t aware of the risks. Michael Stern’s JDS, for instance, is completing a 60-unit project bounded by Beach 5th and Beach 6th streets, Seagirt Avenue and the ocean, where current rents range from $2,650 to $4,300. All of the development’s livable spaces and electric closets are located above the flood zone, and the design also includes flood vents — permanent openings that let water pass through the foundation walls of a building’s exterior.

And the city, too, is taking heed. Late last month, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced an investment of $145 million for up to seven projects — including raising the shorelines around Edgemere and Rockaway Community Park — meant to help protect the area from future coastal storms and flooding.

Caller said the prospect of another Hurricane Sandy, which he called a “once in a 100-year storm,” did not bother him for several reasons. The site where his firm is building was not hit very hard during the superstorm, he said, while the project conformed to new resiliency standards, such as not having any residential areas on the first floor.

He also pointed to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ remedial work, which included the restoration of sand to the peninsula’s beaches. But in August 2016, the federal agency released recommendations for an additional $4 billion in infrastructure improvements — including a reinforced seawall along Rockaway’s Atlantic Ocean side of the neighborhood and a concrete floodwall along it’s Jamaica Bay side — to protect the area from another storm. To date, those public projects have not secured the necessary funding, the New York Times reported.

Regardless, Caller told TRD, “We’re not concerned.”

“It’s interesting that the other side of the bay got hit much harder,” he said, “so as long as the winds blow the same way, we should be in good shape.”