When news broke this year that Jamestown Properties was selling the Chelsea Market building to Google for $2.4 billion, the story went viral.

But behind the scenes, it was the attorneys, not the CEOs, who were hashing out the finer points of the monster deal.

“When the numbers get up into the stratosphere, there’s a certain level of scrutiny, a level of complexity,” said Joanne Franzel of the law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, who represented Jamestown in its sale of the 1.2 million-square-foot building.

Related: The law firms with the highest volume of loans and sales

Representing Google on the other side of the deal was Robert Sorin of Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson. His relationship with the tech giant dates back to 2010, when he won a competitive bidding process to represent Google in its $1.8 billion purchase of 111 Eighth Avenue.

But the Chelsea Market was a far more complex transaction given the food market and extra development rights, he said.

“The scope of the due diligence is just vastly expanded, because I’ve got to understand how this potential development is going to work and get all the land use and zoning lawyers involved,” he said.

But that deal was something of an outlier in today’s market.

Related: The regulation situation

While the first half of 2018 finally saw the market turnaround from two years of declining activity, the Google trade was in a category of its own — it was the second most expensive sale in New York City since the GM Building sold for $2.8 billion in 2008.

Nonetheless, the reboot of the investment sales market provided a relatively steady pace of work for New York’s real estate attorneys in the last year. Attorneys working on debt and office leasing, meanwhile, continued to see robust activity.

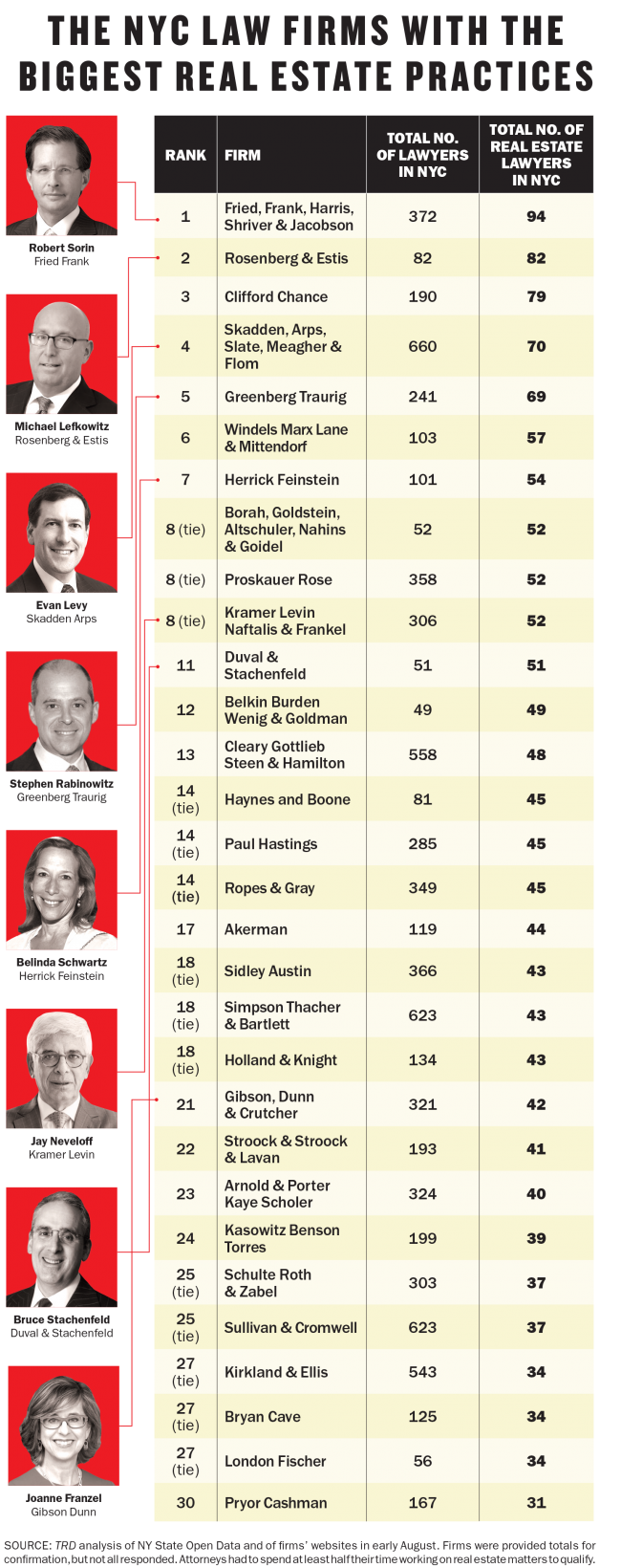

This month, against that brewing backdrop, The Real Deal stacked up the city’s top law firms by biggest real estate practice. We also ranked firms by the dollar volume of the commercial sales and loans they handled.

By headcount, the global firm Fried Frank snagged the top spot for the second consecutive year, with 94 real estate attorneys.

The real estate specialty firm Rosenberg & Estis clocked in at No. 2 again, with 82 attorneys. It was followed by perennial powerhouses Clifford Chance and Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, which had 79 and 70 attorneys in their real estate departments, respectively. Greenberg Traurig rounded out the top 5, with 69 real estate lawyers.

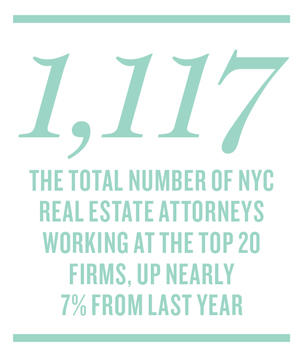

In total, the early-September snapshot found 1,117 real estate lawyers working at the top 20 firms. That’s up nearly 7 percent from 1,046 last year and up more than 11 percent from 1,003 in 2016. (The top 30 firms — TRD expanded the ranking this year — had a combined 1,486 attorneys).

For transactional real estate attorneys, an increase in mergers, acquisitions and competition among lenders is creating movement in the market, helping to bring more work in the door.

Meanwhile, many are gearing up for 2019, when the impacts of President Donald Trump’s tax reform package will come into sharper focus and a new attorney general will take office in New York.

A rueful group

A few months ago, Duval & Stachenfeld hosted what founding partner Bruce Stachenfeld called one of its regular “Scotch and cigar” networking events.

On this occasion, the room was full of CEOs at various lending institutions: banks, insurance companies, private equity funds.

“One of the agenda items was, ‘Who has the upper hand, the borrower or the lenders?’” recalled Stachenfeld, whose firm ranked No. 11 with 51 attorneys.

“Every single one of them said the borrowers are holding the upper hand,” he said. “It was a rueful group.”

And the feelings percolating among the “Scotch and cigar” crowd are being seen in the stats.

Competition among lenders has grown over the past year, especially as equity players who are wary of a potential downturn have shifted their focus to providing debt.

That dynamic, coupled with fewer quality deals to chase, has given borrowers the upper hand in negotiations, according to attorneys who work with both lenders and borrowers.

Eddie Frastai, a partner in the real estate group at Clifford Chance, said that in certain instances lenders are relaxing their underwriting standards when it comes to things like carve- outs and loan-to-value ratios.

For the attorneys, he said, that means trying to ease the stress for lenders while also making sure borrowers are protected.

“In terms of structuring transactions and doing the paperwork, I think the nuts and bolts are still the same, but you’re often trying to figure out creative solutions,” Frastai said.

Skadden Arps partner Evan Levy, who chairs the firms’ real estate capital markets practice, said he’s seeing these new dynamics play out at the negotiating table as well.

“We have clients that we represented in financing properties two or three years ago that are back in the market for refinancing, looking for higher proceeds and getting higher proceeds,”

he said.

“[But it’s] not based necessarily on dramatically higher performance or returns, but on a perception of increased asset values and more readily available financing,” he added.

733 Third Avenue, where Rosenberg & Estis expanded its offices

The environment has improved somewhat since last year at this time. Last year, attorneys told TRD that there were more signs of stress — with loan restructurings and joint-venture partnerships — and that they were generally helping clients get ready for a downturn in the economy.

But after two straight years of declines in investment sales, activity in the five boroughs climbed 20 percent to $21.6 billion in the first half of the year from the same time in 2017, according to the Real Estate Board of New York.

And on the office leasing side, Manhattan recorded 15.36 million square feet of new leases in the first half of the year — the highest total for that stretch in more than three years, according to CBRE.

All of that is not to say there aren’t issues brewing.

Some attorneys noted that they’ve seen more fights among players in the capital stack.

One of the most high-profile cases came this year, when Ian Bruce Eichner sued his partners Fortress Investment Group and Dune Real Estate Partners over control of their Flatiron District condo tower at 45 East 22nd Street. The partners eventually settled the case when Eichner landed a $168 million condo-inventory loan in June. But the situation highlights what some attorneys say is a growing trend of partners battling it out. “I’m seeing fights among partners, disagreements among tranches of debt,” said Jay Neveloff, chair of the real estate group at Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel, which landed in a three-way tie for No. 8 with 52 attorneys. “All the while the deals are fundamentally the same deals; it’s just the expectations have changed.”

Slow and steady

Most of the top real estate law firms in the city either held their headcounts steady or grew them slightly over the past year.

Managers said they wanted to make sure they could handle their current workloads but also didn’t want to get bloated.

Greenberg Traurig, for one, added nine attorneys over the past year, pushing it to its final total of 69 and its No. 5 spot.

Stephen Rabinowitz, chair of the firm’s New York real estate practice, said last year the group added only one partner, who focuses on leasing, to its senior ranks.

“Most of the growth has been on the associate level to staff up for our existing workload,” he said.

He added that when hiring associates, the firm prefers to hire “well-rounded lawyers, so that we can slot them in wherever we find the need.” “Otherwise, they can end up being idle when one area is quiet,” he added.

He added that when hiring associates, the firm prefers to hire “well-rounded lawyers, so that we can slot them in wherever we find the need.” “Otherwise, they can end up being idle when one area is quiet,” he added.

For its part, Clifford Chance added 11 attorneys.

Ness Cohen, chair of the firm’s real estate practice in the Americas, said the growth was a combination of associate-level and lateral hires, with new attorneys bolstering the tax and fund/investment-manager departments.

That field of expertise, Cohen noted, is usually the main factor driving hiring, but he added that it doesn’t hurt when a lawyer can bring in a significant book of business.

“The funds partner did have a very significant relationship with an asset manager that, frankly, by itself is a practice,’” he said.

Cohen said the firm — which was known for its relationship with big banks before the 2008 crash — is also continuing its push to diversify its client base.

“[Big banks were] thought to be a very good and steady business, and it was for decades until nearly every bank was on the edge of bankruptcy,” he said. “I think we find ourselves now with a more level mix.”

Meanwhile, Rosenberg & Estis held its headcount steady, adding just one attorney. But after a few years of rapid expansion — between 2014 and 2015, it grew to 72 attorneys from 44 — the firm took an extra floor at the Durst Organization’s 733 Third Avenue.

“We were pretty maxed out prior to this,” Rosenberg & Estis’ Michael Lefkowitz said. “We can see we’re going to be able to stay on a path of moderate growth. This way, we’re positioned now for the next few years — over the term of this lease — to be able to grow in place.”

Figuring out a real estate giveaway

Around this time last year, Congress was getting ready to unveil its plan for the most significant tax reform legislation the country had seen in 30 years. Now, with the first full year of that tax reform wrapping up, real estate attorneys are working closely with their tax-attorney colleagues to figure out its finer points.

One of the biggest issues to emerge from the overhaul for the real estate industry is so-called “opportunity zones,” which allow investors to defer capital gains taxes on income until 2026 in exchange for investing capital in designated low-income communities through properties or businesses.

“Every client is wondering whether their site will work, whether it fits into one of these zones,” said Belinda Schwartz, chair of the real estate department at Herrick Feinstein.

“It is a very hot topic,” she added. “The language for these zones is rather pithy, and we’re trying to all figure it out.”

Venture capitalist Ross Baird of Village Capital Group told the Wall Street Journal in July that the program “was written by and for real-estate investors.”

And New York real estate investors are already lining up to get a piece of the action.

Keith Rubenstein of Somerset Partners is working on putting together a $200 million opportunity zone fund for new projects in the South Bronx. Scott Rechler’s RXR Realty plans to raise $500 million, mostly by tapping high-net-worth individuals. And Youngwoo & Associates is teaming up with real estate investment startup EquityMultiple to raise $500 million for an opportunity fund focused on Washington Heights and the South Bronx, as well as Los Angeles, Detroit and elsewhere.

But the Treasury Department has yet to outline the parameters for implementation, so questions are still swirling. Attorneys will also get a clearer picture of how the new overall law will impact their real estate clients when the Treasury Department issues its guidance.

Issues like the new 20 percent reduction on pass-through income for sole proprietors and LLCs, or the 100 percent depreciation allowance bonus on the purchase of business assets — up from 50 percent before — are all being closely watched in the industry.

Wayne Cook, an attorney at the firm Windels Marx Lane & Mittendorf, said the new $10,000 cap on homeowners’ deductions for state and local taxes “will bring down some pricing in the market.”

“I still think these deductions being lost by a certain component of our industry will not really hit us until 2019, when we have to write those checks and realize what the tax consequence is,” he said.

“We’re almost living at this point where we don’t believe it yet,” Cook added. “But it’s coming.”