Everywhere Paul Massey looks these days, he sees a problem that he’d like do something about. In April, he spotted four homeless people near his Midtown office. “Homelessness is a crisis that hasn’t been addressed in three years. I don’t think there’s housing being created on any kind of scale,” he complained.

Other things trouble him, too: the strained relationship between citizens and the police, failing schools and the lack of visionary infrastructure projects à la Michael Bloomberg. “Where is the next High Line? Where’s the next 7-line extension that creates Hudson Yards? I’d like to see those kinds of initiatives in every one of the boroughs.”

In the end, he said, “I’m pro-everything, which is like every other 56-year old guy in New York.”

Except Massey [TRDataCustom] is not like every 56-year-old in the city.

He’s a clean-cut Irish boy from Boston who made his way into the city’s ultracompetitive commercial brokerage business, fell on the precipice of bankruptcy, fought back and turned himself into a multimillionaire 10 times over.

Most importantly of all, he is a political newcomer running to be the Republican candidate for mayor in a year when he’d be going up against an incumbent Democrat, and where Republicans are outnumbered by more than 6 to 1.

Needless to say, he is being viewed as an extreme — albeit somewhat curious —underdog.

“If we had to make this call today, I would say this is a long-shot candidacy — an extremely long-shot candidacy,” said David Birdsell, a political science professor at Baruch College.

Part of that perception has been fueled by the press. Back in August, Massey’s campaign staff announced that he had filed the paperwork to start his mayoral run, only to discover that they had failed to submit one of the required documents. “If Mr. Massey, a Republican, wanted to project the image of a capable manager, his first act as a declared candidate did little to help that cause,” read the story in the New York Times.

According to one political expert, the oversight was a major fumble. “If you’re running for mayor, your first shot out of the gate in the Times is important. I think that story signaled to a lot of folks that this wasn’t really worth paying attention to.”

That same month, a Politico article quoted two unnamed real estate players who described Massey’s political foray as a “mid-life crisis.”

The irony, of course, is that within NYC real estate circles, Massey has always been known for his clear-headed and astute management skills. In 1988, after earning his stripes at CBRE, he teamed up with Robert Knakal, a hard-charging Wharton graduate with a photographic memory. Under their newly founded company, Massey Knakal Realty Services, they developed a strategic edge by dividing the New York metropolitan area into different territories and delegating each territory to a single agent. The system, they said, allowed agents to know a neighborhood better. The two partners, who agreed to a 50/50 split, seemed to complement one another: Massey was thoughtful and good at managing the staff, while Knakal brought the blustery personality of a driven broker. “Bob is normally seen as the dealmaker, but Paul made a lot of bigger, tougher deals,” said Darcy Stacom of CBRE, who specializes in bigger-ticket transactions. “Every time there was an instance where they crept into my space, those were Paul’s relationships. Bob is a traditional broker — push ’em, keep the pressure on. Paul takes more of a long view. He’s good at the situations where you’re dealing with a couple of big players.”

The irony, of course, is that within NYC real estate circles, Massey has always been known for his clear-headed and astute management skills. In 1988, after earning his stripes at CBRE, he teamed up with Robert Knakal, a hard-charging Wharton graduate with a photographic memory. Under their newly founded company, Massey Knakal Realty Services, they developed a strategic edge by dividing the New York metropolitan area into different territories and delegating each territory to a single agent. The system, they said, allowed agents to know a neighborhood better. The two partners, who agreed to a 50/50 split, seemed to complement one another: Massey was thoughtful and good at managing the staff, while Knakal brought the blustery personality of a driven broker. “Bob is normally seen as the dealmaker, but Paul made a lot of bigger, tougher deals,” said Darcy Stacom of CBRE, who specializes in bigger-ticket transactions. “Every time there was an instance where they crept into my space, those were Paul’s relationships. Bob is a traditional broker — push ’em, keep the pressure on. Paul takes more of a long view. He’s good at the situations where you’re dealing with a couple of big players.”

They were not an overnight success. At one point, the two men applied for credit cards to cover the bills. In fact, it took a whole decade before they grabbed the top market share in the $5 million-to-$50 million investment sales category. The company eventually ballooned into a $2 billion-a-year business. They granted equity to some of their top producers, but retained the majority ownership.

In 2007, the partners had a major fight after CBRE submitted an offer to buy the company. Knakal wanted desperately to sell; Massey wanted to hold on.

“There were flaming emails, acrimonious meetings. They wanted to split the company in two,” said one person with knowledge of the dispute, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “People were trying to tell them to calm down. It would be bad to present that face to the public.”

In an interview with The Real Deal, Knakal said, “It was a great number, more than I thought the company was worth at the time.”

But Massey held firm. Taking the long view, he told Knakal, “Bob, we have a lot more wood to chop.’”

The decision proved wise. In 2014, they sold their company to Cushman & Wakefield for $100 million, an amount that turned out to be more than CBRE had offered.

Which brings us to where Massey is now: a well-liked veteran of the industry with a sterling reputation who has cashed in his chips but is now apparently hungry for a much bigger challenge.

“When I talked to him, I said, ‘Paul, you’re going to have to give 2,000 percent of yourself right up to the election. You’re going to have to go to every street in every neighborhood. What you had 100 people doing at Massey Knakal, you’ll have to do that yourself,” Stacom said.

At 6-foot-2 with steely blue eyes, the former broker carries himself with an air of understated authority. He is ignoring the snickering and forging ahead with a candidacy that aims to cast himself as a pro-business successor to Bloomberg. Toward that end, he is branding himself as the anti-Bill de Blasio, a politician who cares less about party lines and more about actually managing the city. De Blasio, he says, spends more time being a national crusader against income disparity than he does actually serving the voters who got him elected.

“He’s spent a lot of time outside the city, focusing on being the national leader of the progressive movement. I’m certain that’s not in the job description,” Massey said. “I think it’s the mayor’s job is to look out for the 8 million people here and serve them with a singular focus. We think this is more of a CEO, managerial job than a political idealogue job.”

He added: “You can’t have the luxury of being progressive if you have a poorly run city.”

In response, a spokesman for the mayor issued the following statement: “Under Mayor de Blasio, crime just hit another all-time low, jobs are at record highs, the city is building and preserving affordable housing at a record pace, while graduation rates and test scores continue to improve. We are happy to match that record against anyone.”

Thus far, Massey has doled out little in terms of policy, a weakness that has not gone unnoticed by his would-be supporters in the real estate industry. “I want to support him, but tell me what I’m supporting. What’s the platform?” said one real estate insider, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

In his first press interview since launching his campaign, Massey told TRD he would finish developing his policy road map in the next month or two.

In other words, he is in no rush.

But he has been doing his homework. In the fall, he met with Stu Loeser, who served as press secretary for Mayor Bloomberg. (The billionaire businessman’s chances, incidentally, were initially described by the Times as “remote.”) The two men talked about the mechanics of sanitation routes, of all things. But Loeser came away with a positive view of the real estate entrepreneur. “Paul’s understanding of how the ways that New Yorkers get around have changed in the last five years was particularly impressive, and he has already put a lot of thought into how New York can tackle traffic problems,” he said. “He sure seems to be talking to a lot of people, especially in the boroughs, and absorbing it all.”

In June, Massey tapped David Amsterdam, an executive at SL Green, to become his full-time campaign CEO. And his campaign has made several high-profile political hires from both parties, including Bill O’Reilly and Jessica Proud, who ran former MTA Chairman and Deputy Mayor Joe Lhota’s unsuccessful 2013 Republican bid against de Blasio; Alex May-Sealey, a former White House staffer who worked with First Lady Michelle Obama; and Democratic consultant Doug Schoen, who advised the Clintons. But among the most impressive hires has been Ann Herberger, who had been a prolific fundraiser for Jeb Bush and his brother George W. Bush.

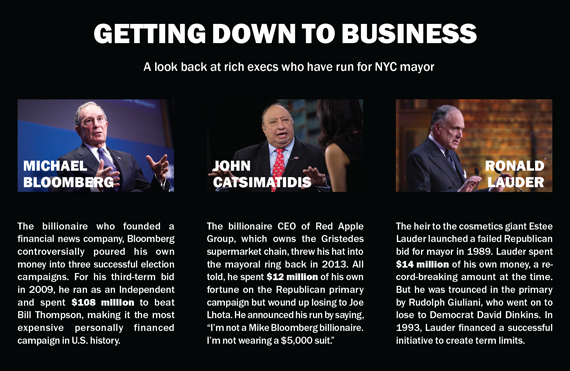

While he may not be going out of his away to do a lot of press appearances, Massey has been furiously trying to raise money, and for good reason. Bloomberg famously spent $108 million on his 2009 re-election efforts, while John Catsimatidis pumped $12 million of his own money into his failed Republican mayoral primary bid.

Because he is not planning to participate in the city’s matching-fund program, Massey won’t be held to the $7 million spending limit dictated by matching regulations. He told TRD he is hoping to raise double what’s raised by his competitors who are taking matching funds.

Unsurprisingly, he is looking to leverage his real estate connections. Within the industry, feelings are mixed about de Blasio. “None of us are really happy with the current administration. I’m certainly not, for a variety of reasons,” said CBRE’s Stephen Siegel.

In recent weeks, Massey’s colleagues at Cushman & Wakefield have tried to help his fundraising by blasting out emails and working the phones.

In December, Cushman investment sales broker James Nelson hosted a fundraising reception for Massey at the Falcon Laundry in Williamsburg, a pub-style hipster spot with cracked green leather booths. Tickets for the event were $250 a pop, while Massey sold entry to an “intimate founding members reception” for $1,500 per person.

Still, even among friends, raising money for a long-shot candidate is a hard sell. “Who wants to give money a guy that probably won’t win?” Castimatidis said. “No one wants to be on the mayor’s shit list.”

So how much exactly does Massey need to raise?

Political consultant Bradley Tusk, who served as the campaign manager for Bloomberg’s 2009 re-election, said, “To win in a general election, he’ll need to spend north of $50 million to even have a shot.”

He added: “I’m not sure if he’s rich enough to do that.”

Indeed, unlike his idol Bloomberg, Massey is not loaded, certainly not by New York standards. He currently lives in the West Village but owns a $1.4 million house in Larchmont and a small home on Cape Cod.

Sources speculated that Massey likely walked away with nearly half the $100 million from the sale of his company, though Massey declined to confirm that sum.

“I would self-fund this if I could, but I don’t have Michael Bloomberg’s net worth. I’m just a small businessman by comparison,” he said.

While the average voter might smirk at the “small businessman” assertion, Massey — who came from a middle-class family of newspaper publishers — has suffered humbling setbacks. Back in 2008, Massey Knakal was hit hard by the financial crisis.

“Eighty percent of the business just went away,” Massey said. “We got close to cutting our budget in half. I had all kinds of nightmares.”

It took him years to financially recover. From 2009 to 2013, the Internal Revenue Service issued Massey and his wife, who then lived in Larchmont, three tax liens for a total of $4.1 million. Massey didn’t pay off the balance of the debt until March 2015, following the sale of the company to Cushman. His spokesperson said he set up an installment plan with the IRS and paid everything off earlier than scheduled, with full penalties and interest.

“The odds have been stacked against him his whole life, and he’s come out ahead every time,” Amsterdam said. “He’s immune to that concept of the odds. He just thinks, ‘I’ll stay awake longer, I’ll work harder than everyone else.’”

Birdsell noted that Massey has massive ground to cover with city voters. “There are plenty of people who pay close attention to New York politics who don’t even know who the guy is, much less rank-and-file voters.”

It took Massey until December to begin ramping up his public appearances. He spoke at a luncheon for the Real Estate Board of New York and at an event held by the Partnership for New York City, two strategic, well-aligned choices for a business candidate. At the REBNY luncheon, Massey, a humdrum speaker, talked from 10,000 feet about his political priorities — and took hits at the current administration. “The police will never have to protest me outside my gym at 10:30 a.m.,” he said, referring to a showdown in September over police contracts. “I’ll already have been at work for four or five hours.”

In fact, Massey’s calendar is pretty booked these days. In addition to meeting with policy advisers, he’s been walking the streets, talking to business owners and people who lost their homes in Hurricane Sandy.

Not that anyone would know about it.

“Paul wouldn’t let me bring press when we did the tour,” O’Reilly said.

“There’s time for that,” the candidate replied.

In a way, Massey seems to most relish the glad-handing. He happily recalled a moment in December when he was canvassing for potential voters on the Staten Island Ferry. A middle-aged woman approached him out of the blue, he said.

“You’re a good person,” she told him.

“How do you figure that?” he asked.

“The tone of your voice is good. You’re running for mayor, right?”