In a city ruled by conservative straight-lined skyscrapers, Bjarke Ingels’ 2 World Trade Center — when and if it is finally built — will stand out as a playful, teetering staircase. Designed as a series of seven precariously stacked blocks, the 3 million-square-foot building rising over Lower Manhattan doesn’t so much want to go upward as topple over. In a Wired story last year, Ingels likened the process of designing 2 World Trade Center to “playing Twister with a 1,300-foot high-rise.”

It’s a bold experiment considering that back in 2015, when he and Larry Silverstein began discussing the project, the Danish architect had never even designed an office building in New York City. He’d made waves in other arenas, with his pyramid-shaped rental building for the Durst Organization in Midtown West and a mixed-use development in Copenhagen that drew praise for its figure-eight shape. But this was one of the final pieces of the World Trade Center complex, the second-tallest tower of the six planned in the most historically fraught site in the city. His lack of experience aside, enlisting Ingels to design the tower also meant jettisoning one of the most renowned architects in the world: Norman Foster. Silverstein had tapped Foster, who designed the Hearst Tower and 50 United Nations Plaza, for the project in 2006.

Ultimately, it boiled down to the fact that the Murdoch family wanted Ingels. Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. and 21st Century Fox had pledged to take 1.3 million square feet of the building’s total 2.8 million, and having Ingels’ design became a condition of the deal. But in January, Murdoch pulled out of the lease. Yet since that time, Silverstein has nevertheless stuck with Ingels’ plan. “I suppose it’s a reflection of change in taste, and in the change in architectural language,” Silverstein told The Real Deal. Tech companies, he added, place a premium on outdoor space, a feature that Ingels’ design heavily incorporates.

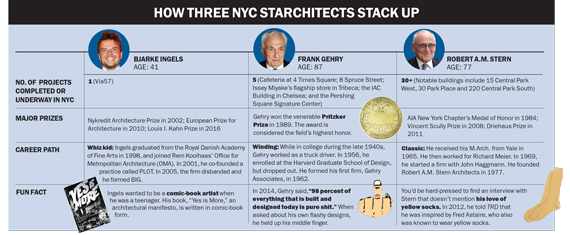

But what has also changed over the last year is Ingels’ stature in the world of architecture and New York real estate. Around the time he usurped Foster for 2 World Trade Center, his firm, Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), was selected to co-design Google’s new headquarters in California with fellow star architect Thomas Heatherwick. Earlier this year, BIG was tapped to design Vornado Realty Trust’s Two Penn Plaza, and Tishman Speyer’s Hudson Yards project at 66 Hudson Boulevard. In April, Ingels was named by Time magazine as one of the most influential people of 2016. If there was ever any doubt before, there is none now: Ingels is officially a “starchitect.”

At 41, he has skyrocketed to fame in a way that few before him ever have. Architecture notoriously demands a long view. Paul Goldberger, a Pulitzer Prize-winning architecture critic, noted that many architects must work 20 to 30 years before they attain the admiration that Ingels enjoys. Or as Helmut Jahn, 76, a German-born architect who recently designed a luxury condominium for Time Equities at 50 West Street, put it, “The distance of time is something that makes a building better or worse. A good building gets better with time, the bad buildings you forget.”

Many see Ingels’ rapid ascension as a sign that there is now a race to anoint starchitects. Certainly, the digital age is a factor. Social media can amplify an architect’s exposure and rapidly spread compelling new renderings. As a result, buildings can gain recognition without even being built. In December, architect Mark Foster Gage released a theoretical 102-story Art Deco residential tower for Billionaires’ Row. The renderings went viral even though there are no plans to actually build it. “There’s no question, in the age of social media and in the age of everything happening faster, architects’ careers are also happening faster,” Goldberger said. “The need for new stars keeps coming up. And whether we keep the old ones or decide they’re tired or throw them away will be an interesting question.”

Not surprisingly, some have been highly critical of the starchitect phenomenon. Danish architect Thomas Juul-Hansen, who designed the interior of Extell Development’s One57 and both the exterior and interior of HFZ Capital’s High Line condominium at 505 West 19th Street, called Ingels the “Tony Robbins” of architecture. He said the architect’s “social gifts” and his eye-catching projects have helped feed his larger-than-life persona. “It’s definitely sustainable for him,” he said. “Whether it’s good for the profession or not, I’m not sure, because the idea of doing something for attention is never a good one. Unfortunately, that’s the way the world is today.” He then added, “It’s probably a sustainable model. If you look at Kim Kardashian, what does she actually make? She makes attention.”

Not surprisingly, some have been highly critical of the starchitect phenomenon. Danish architect Thomas Juul-Hansen, who designed the interior of Extell Development’s One57 and both the exterior and interior of HFZ Capital’s High Line condominium at 505 West 19th Street, called Ingels the “Tony Robbins” of architecture. He said the architect’s “social gifts” and his eye-catching projects have helped feed his larger-than-life persona. “It’s definitely sustainable for him,” he said. “Whether it’s good for the profession or not, I’m not sure, because the idea of doing something for attention is never a good one. Unfortunately, that’s the way the world is today.” He then added, “It’s probably a sustainable model. If you look at Kim Kardashian, what does she actually make? She makes attention.”

Ingels could not be reached for comment.

The path to celebrity

Here in New York, the most prolific and one of the best known starchitects is Robert A.M. Stern. He is famous, of course, for 15 Central Park West, which was completed in 2008 and went on to generate roughly $2 billion in sales. Within the world of design, the building — which itself was a replica of the prewar buildings designed by renowned architect Rosario Candela— became a trendsetter. Yet within the architecture world, Stern’s projects tend to be regarded as well-made but safe: He favors meticulously detailed limestone over high-concept geometry. Critics have referred to him as the Ralph Lauren or, alternatively, Martha Stewart, of architecture.

At 77, Stern cannot pinpoint a singular project that propelled him to mega-fame. He told TRD that in the 1980s, he starred in an eight-part, eight-hour documentary on PBS that helped gain him “a certain level of noticeability.” But ultimately, he said the collection of buildings he has designed, the books he has written and the books that have been written about his projects have together helped him achieve stardom.

“I think it’s hard to establish yourself as an individual,” he said. “It’s a matter of time, it’s a matter of the right project, it’s a matter of the right succession of projects. An architect who only has success on one project is what I’d call a Johnny-one-note architect. Or a one-trick pony.” Artists face a similar conundrum, he said. “They have this flashy show in Chelsea and then you go to the next show and the next show and you wonder, ‘Where is this artist going?’ And suddenly, the artist is showing across the river.”

Zaha Hadid

But there are trajectories that starchitects of all ages seem to have in common. One road to architectural glory looks something like this: Study at a well-known architecture school (or in the case of Frank Gehry, study, and then drop out of one of the best known programs, Harvard Graduate School of Design); join a firm headed by a high-profile architect; and lastly, form a new firm, all the while racking up prizes, the most vaunted being the Pritzker Prize, the architect’s version of the Nobel. As with other industries, working at the right place matters. Both the late Zaha Hadid, the Iraqi-born British architect known for her cutting-edge use of curvaceous geometry, and Ingels started their careers at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), the international firm headed by the Pritzker Prize-winning Rem Koolhaas. Hadid, who died earlier this year, won the Pritzker in 2004, becoming the first woman to win the award. Ingels, meanwhile, has been mentioned as a possible recipient.

Dan Kaplan, senior partner at the New York City-based FXFowle, the firm that is currently designing the expansion of the Jacob K. Javits Center, called OMA a “starchitect hatchery.” He added, “There seems to be something in the water there, and I think a lot of it has to do with elevating marketing and brand thinking into the design realm.”

Unlike the recent crop of starchitects, it took several years for Pritzker Prize winner Gehry to get a gig in New York City. Among living architects, Gehry occupies the highest stratum of fame. His design of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, completed in 1997, was called the “greatest building of our time” by fellow architect Philip Johnson. And yet, Gehry’s first New York City project wasn’t until 2000, when the cafeteria at Condé Nast’s old headquarters at 4 Times Square was finished. He then went on to design 8 Spruce Street, a rental skyscraper ridged with ripples that flow skyward and dubbed New York by Gehry; Issey Miyake’s flagship store in Tribeca; the IAC Building in Chelsea; and the Pershing Square Signature Center.

More so than with Stern and Gehry’s generation, charm, good looks and a coordinated marketing effort go a long way among today’s rising stars when it comes to establishing a reputation. Architects who spoke to TRD described Ingels as one of the most charismatic architects that they know, adept at capturing the attention of an entire room. Indeed, he has created a well-honed brand for himself: He’s written a book, “Yes Is More,” that doubles as a tagline philosophy on design; he’s done a TED talk; his firm has a YouTube channel; and he documents his travels on Instagram. This isn’t to say that a flashy social media account is all it takes to become a world-renowned architect — but it certainly provides an opportunity for constant exposure in a way that was not available to the likes of Renzo Piano or Richard Meier for the majority of their careers. “Zaha, as far as I’m aware, didn’t have an Instagram account,” said Jeffrey Inaba, co-founder of the architect firm Inaba Williams, who previously worked at a consulting firm started by Rem Koolhaas. Fame for an architect, he added, doesn’t only happen “by being good at social media.”

The invisible starchitects

For those who will never ascend to such heights, who will never earn even a fraction of the millions in commissions, the designation of starchitect can be galling because it creates the illusion of an isolated genius behind each design. In reality, an architect like Stern works with a large team of designers, something that he and others readily acknowledge.

“The world at large likes to believe that the principal architect is doing everything, starting with the sketch to the most technical drawings, and in the evening hours, he’s cleaning the office,” Stern said. “Not quite true. This is truly a collaborative process.” Ingels’ firm, BIG, has more than 400 employees worldwide, 11 of whom are partners.

Sometimes, the collaborators are from another firm. Jim Davidson, a partner at SLCE Architects, one of the city’s most prolific firms, said that roughly 35 percent of the firm’s commissions come from projects with starchitects. His firm is currently working with Hadid’s firm to design the Moinian Group’s planned condominium at 220 11th Avenue. On her High Line project, Hadid worked with Ismael Leyva Architects. The role of firms like SLCE oftentimes is to assure the developer that the lead architect’s vision is buildable. Many of these architects are not licensed to work in New York and need the assistance of a local firm to navigate the city’s agencies and building codes.

T.J. Gottesdiener, managing partner at Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, the firm behind 1 World Trade Center, said the starchitect designation is simply a marketing tool that demeans the profession because it draws attention away from the actual projects. “Do I really believe that Daniel Boulud is back there chopping my onions? No, of course not,” he said. “I don’t believe they’re making the soup. When I buy a Calvin Klein suit, do I actually believe that Calvin Klein designed that suit and sewed it for me? No. Well, that’s kind of what’s happened in architecture today. Any star architect that you name, he’s not drawing all those lines and deciding all those issues about the projects.”

Still, developers appear to be willing to pay up. But exactly how much is something of a mystery. Information on standard architecture fees in New York is sparse, largely due to competitiveness between firms and a fear that transparency would look like collusion to federal investigators, said Peggy Deamer, an architecture professor at Yale University. When asked, Stern would only say that his firm is “probably not the cheapest in Manhattan.” Via57’s developer, Douglas Durst, wouldn’t disclose Ingels’ fees but said, “We’d love to work with him in the future, but I don’t know that we could afford him.”

A better skyline?

Nevertheless, even architects who dislike the starchitecture trend concede that it has raised the design bar, especially for residential real estate in New York City. Juul-Hansen said that before Richard Meier’s Perry Street condominium project — two 15-story towers in Greenwich Village finished in 2002 — much of the city’s residential projects were “banal.” Since then, international giants in the profession have started to infiltrate the apartment and condo game, like Rafael Viñoly, Renzo Piano, Jean Nouvel and Christian de Portzamparc. JDS Development’s Michael Stern, who has hired star firm SHoP Architects for several of his projects, said that fierce competition has led developers to pay closer attention to the quality of design. “Everyone collectively has to admit that the caliber of work has been raised,” he said. “Today’s rental buildings are better than yesterday’s condos.”

The High Line has of late been a petri dish for the race in design. Ingels is designing HFZ Capital’s High Line project, a two-building, 800,000-square-foot condominium at 76 11th Avenue. Centaur Properties is also co-developing a two-building condominium project, a 95,000-square-foot complex at 525-531 West 27th Street called the Jardim. Centaur CEO Harlan Berger said that when Related Companies bought the site next to his property and commissioned Hadid to design a condominium, he knew Centaur also needed to hire someone extraordinary. “I was like, ‘Oh my God, how do you design something right next to someone of that caliber?’”

They enlisted Brazilian architect Isay Weinfeld, who has never designed a building in New York before but who provided a “180” from Hadid’s spaceship-like project. Weinfeld’s façade is made of textured concrete and brown brick, which is accented by a series of private terraces. The building is currently under construction. “Every architect on the planet wants to put their fingerprint on that neighborhood,” Berger said. “I wanted to take a chance.”

Yet the view that the starchitecture trend has bettered the city’s skyline is not unequivocal. John Patrick, head of the talent agency Above the Fold, which represents “under the radar” architects, said that the popularity of starchitects promotes diminishing returns in design. If an architect becomes wildly popular for one project, he said, subsequent commissions will likely be derivative — either at the behest of a client looking to capture the hype of earlier projects or due to an architect’s attempt to maintain a recognizable style. The idea plagues artists in all media: The young novelist or musician whose debut is a hit sees every subsequent work measured against it.

Deamer said it can put an architect in a box of his or her own design. “You begin to indulge an image that you’ve gotten a reputation for and then you quickly become a caricature of yourself,” she said. “We’ve seen that happen. I think there are a number of projects that Frank Gehry has done that he shouldn’t be proud of. You know, where it’s just slash and a dash, and there’s his signature, but I don’t think much thought has gone into how that form relates to a context or a program or really rethinking the way a building is going to be built.”

Meanwhile, some architects struggle to strike a balance between repetition and creating a sort of “sibling” relationship between their buildings, according to Goldberger. “If you’re buying art, you want a Rothko to look like a Rothko, not a Picasso,” he said. “Nevertheless, each painting is a little bit different.”

Both those who embrace the “starchitect” term and those who reject it agree, at least publicly, on one thing: that it can distract from the most important aspect of the profession — the product. The building must function for its occupants, Durst said. The name attached to it is secondary. It’s a designation that can prop up an architect’s career, but ultimately, it’s his or her work that will sustain it.

Jahn said, “I think all of us, at least for me and most of my colleagues, we live with that label quite happily but I think we also consider our task, what we actually do — provide housing — a very important task.”

He added: “We don’t fight that we are considered a ‘star.’ We don’t ignore that, but I always took it as a challenge to not just be a star but to be good. There’s a difference.”