For more than four years, nobody knew who bought the only $100 million apartment in Manhattan.

Real estate agents and architects who worked with the buyer were all sworn to secrecy, according to the Wall Street Journal, and even after several rounds of building permit applications to renovate Michael Dell’s 11,000-square-foot penthouse at One57, the name of the billionaire behind “P89-90 LLC” only became known after a loose-lipped insider told a reporter.

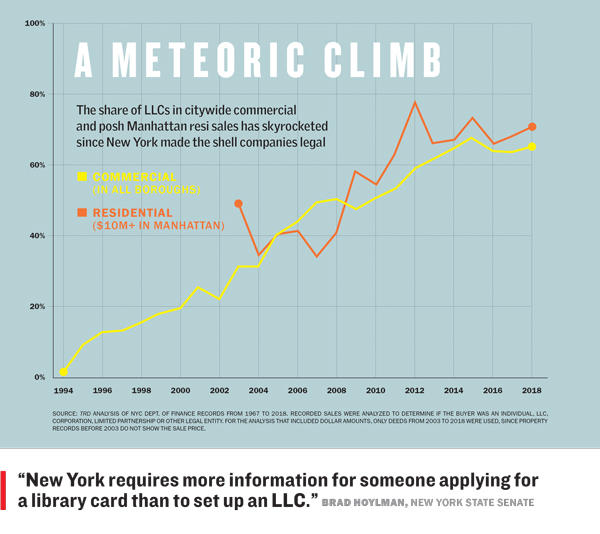

Since becoming legal in New York State in 1994, LLCs — hybrid entities that provide a shield against liability and offer several tax advantages — have become one of the most dominant ways to buy property in the city.

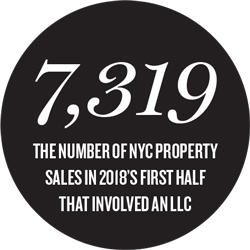

A new analysis of recorded sales by The Real Deal shows that 7,319 real estate deals in the five boroughs in 2018’s first half involved an LLC. Among commercial properties, that accounts for 65 percent of all sales across the city and 71 percent in Manhattan, up from 30 percent and 49 percent in 2003. And in Manhattan’s luxury residential market, 72 percent of condominium sales over $10 million involved an LLC in the same time span — up from 20 percent 15 years ago.

The overall share of LLCs in New York property deals, meanwhile, has steadily risen for more than two decades, as they’ve ascended to become the real estate industry’s favorite investment vehicle.

“It was the entity we’d all been waiting for,” said Holland & Knight’s Stuart Saft, who has worked as a real estate attorney in New York since before LLCs existed.

Though the use of these shell companies is mostly driven by legal and tax benefits in the commercial realm, a common motivator in New York’s posh residential sector is invisibility. Anonymous ownership allows wealthy foreign buyers, celebrities and now even embroiled politicos like Michael Cohen and Paul Manafort to fly under the radar when buying luxury homes.

“All of these individuals would just prefer that nobody knows who they are or what they’re doing,” said Robert Dankner, president of the New York brokerage Prime Manhattan Residential.

But while LLCs let investors safely accumulate more assets and block creditors and others from going after their holdings, that has come with some notable social costs.

Among other red flags, federal law enforcement is increasingly tying international money laundering to the use of shell companies and real estate. And anonymous spending on elections has increased over the years, particularly in New York, where a campaign finance loophole allows real estate and other business owners to make virtually unlimited political contributions by using LLCs.

“New York requires more information for someone applying for a library card than to set up an LLC,” said state Sen. Brad Hoylman, a Democrat whose district spans Manhattan’s core. “An anonymous P.O. box isn’t enough information for the state to do its job and keep track of who’s really behind the creation of these corporate entities.”

Nobody’s real estate

Even though property deeds are publicly available through the city’s Department of Finance, shell companies with addresses and signatures leading only to an attorney or wealth management firm abound.

And the specter of unnamable foreign billionaires buying up New York’s housing stock has become a popular rallying cry in the city and has increasingly sparked political discussions on affordability and the flow of illicit money from overseas.

On that front, there have been some significant reforms in recent years.

Since 2015, the Department of Finance has started to collect more information from residential LLCs by asking for a full list of company members on their annual tax returns. In 2016, the U.S. Treasury Department began ordering title insurance firms to report the real names of people behind luxury residential purchases. And as of this year, the IRS requires foreign LLC members with at least 25 percent ownership of the entity to reveal themselves in annual filings.

In other instances, however, increased disclosure has simply driven more buyers to use LLCs, as the case has been with New York City co-ops. For years, information on individual co-op owners was hard to come by, until Gov. George Pataki signed a law in 2002 requiring the Department of Finance to post co-op transactions in its online database.

That sparked a push by investors and brokers to encourage co-op boards to accept LLC buyers. And the effort is finally starting to catch on as co-op boards have become more receptive, said Warburg Realty broker Steven Goldschmidt, who specializes in the high-end co-op market.

“A lot of co-op boards have members who decided, ‘Hey, [LLCs] might not be a bad idea for me,’” Goldschmidt said. “So it’s one of those things where the initial reaction might have been cautious, but as the law and the process has evolved, I think people are more and more comfortable with it.”

In 2013, however, the New York state Senate moved to disqualify homeowners from the city’s condo and co-op tax abatements if they own their properties through LLCs. That may account, at least in part, for the noticeable dip in the use of LLCs in luxury residential sales after 2012: The share of Manhattan transactions above $10 million that involved one dropped from 74 percent to 63 percent in a single year and has not returned to its previous level since.

“I’ve seen people not purchase because of that — because they don’t have that flexibility,” Dankner said, though he added that any real effect on the market from that measure would have been “marginal.”

There have been several attempts in the state Senate and Assembly to reform the LLC Act of 1994. Most recently, Hoylman introduced a bill in September 2017 that would require LLCs in New York to disclose their beneficial owners, which would then be recorded in a public database.

But the bill did not make it out of committee before the close of the 2018 session, and the Albany lawmaker is still going to bat.

When the transparency bill was announced, Hoylman took aim at America’s most famous real estate mogul, President Donald Trump, noting that “70 percent of buyers of Trump properties can hide their identities behind LLCs.”

Despite recent reforms and the ongoing push to bring more transparency to real estate purchases, Saft said the veils provided by LLCs largely remain intact.

“It’s wonderful that people can keep their assets anonymous and don’t have to worry about trolls going after them,” he said. “I think it’s certainly in our best interest to have as many celebrities and billionaires having homes in New York City [as we can]. They pay their taxes, they pay to operate the buildings, and New York City needs all that money.”

The rental curtain

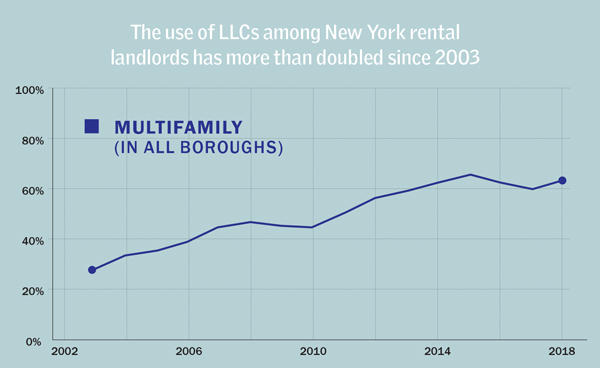

The use of LLCs has also allowed thousands of New York landlords to hide their identities, which makes it harder for tenants to bring charges against them in court. And increased disclosure measures focused on home purchases haven’t done much for the 5 million-plus residents in Manhattan and the outer boroughs who rent their homes.

As an April New York Times piece on the subject pointed out using census data, 92 percent of multifamily housing nationally was owned by individuals two decades ago. By 2015, that number shrank to 75 percent.

In New York City, TRD’s analysis shows that 60 percent of multifamily building sales last year involved an LLC, which means opaque ownership of rental apartments in the five boroughs is several times higher than the national average.

Not being able to identify your landlord — or even know if that person, company or investor group owns several other buildings — is a massive hurdle for tenants seeking to bring claims of abuse and housing violations against them, said Seth Miller, a tenant attorney at Collins, Dobkin & Miller.

“It’s very hard to find information on LLCs and who is involved,” he said. “In fact, when you go to court and you want to get discovery of the operating agreement, that’s almost always resisted.”

In cases where the landlord of one big rental building is an LLC, it’s easier to show a pattern of housing violations or tenant harassment, Miller noted. “But if the landlord is, in fact, a famous person who controls several LLCs, it’s very difficult to know that or connect that building to other buildings you might use to show such a pattern,” he said.

Emily Goldstein, senior campaign organizer at the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development, expressed a similar frustration. “It makes it much harder to say, ‘Oh, this is not just an isolated incident,’” she said. “It makes it harder for organizers to strategically go to buildings that may need assistance.”

Proving common ownership of separate properties in court can tie up tenant claims for considerable periods of time. A class-action lawsuit against Harlem landlord Big City Realty — accusing the firm of overcharging tenants — became the subject of a March appeals court hearing, for instance. And that hearing largely revolved around a series of LLCs and whether or not they were really a part of the same “enterprise.”

The complaint, first filed in 2016, had been dismissed by a lower court before tenant attorneys could conduct the discovery needed to demonstrate how the LLCs were allegedly all connected to the administration of the building.

The tenant attorneys in that case declined to speak for this story.

“The ability to hide the real owner of real estate has been a negative development and is not consistent with legal policy that applies to property in general,” said Susan Pace Hamill, a University of Alabama law professor who published research on LLCs when they began to explode in popularity in the 1990s.

Mystery lenders

It’s not only tenants who are often left not knowing who owns the roof over their heads. High-powered real estate investors in some cases don’t even know who actually owns their debt.

And getting a court order to find out can require a lot of time and money, said Duval & Stachenfeld attorney Tim Pastore, who litigates commercial real estate finance cases.

“Typically, you would think if you borrow money from someone you know who they are,” Pastore said. But loans are often sold, he noted, and there’s no guarantee that the original borrower will know who the buyers are.

Pastore is representing Sharif El-Gamal’s Soho Properties in an ongoing dispute with an entity called 560 Seventh Avenue Lender LLC.

Soho Properties and its partners believe one of the members of that entity is the private real estate firm Hidrock Properties, which they allege violated a nondisclosure agreement before buying the mortgage on their Dream Hotel project at 560 Seventh Avenue, court filings show.

But since the beneficial owners of the LLC are not plainly disclosed, Soho Properties has to get a discovery order from the court to clearly demonstrate who they are.

“If you can raise a claim or defense that bears upon knowing the true [owners of an entity] then, arguably, you are entitled to discovery of the issue,” Pastore said, noting that the discovery process “necessarily prolongs the litigation.”

Time spent figuring out who’s who can get even more complicated when commercial real estate cases involving LLCs are brought to federal court. In those cases, plaintiffs must demonstrate a legal concept known as diversity, which means the parties involved are based in separate states and therefore require a federal court to settle the dispute.

But the clandestine nature of LLCs and their real owners make that extraordinarily arduous and can sometimes lead to disputes being dragged out in the wrong court. “You could potentially litigate a case for years and have the citizenship of a member be identified and then get sent back to state court,” Pastore said.

Signature for hire

During the middle of the 20th century, a woman named Tillie Feldman probably bought more property and took out more loans than any other real estate investor in the city.

Week after week, her name appeared in the New York Times’ “Manhattan Transfers” column, where the most recent building sales and mortgages were reported.

In 1945, she acquired a development site at 800 Seventh Avenue. In 1957, Feldman, who the Times described as “a little old lady in a small Brooklyn flat,” leased Ebbets Field right after Los Angeles Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley sold it to New York developer Marvin Kratter for $3 million. She had at least $11 million in mortgages under her name at the time, about $100 million in today’s dollars.

So why is she not in the real estate hall of fame?

Because she never did any of that, really. Feldman was a signature for hire — a shell. She signed her name so the barons trading Manhattan properties, and borrowing heaps of money to do, didn’t have to, shielding them from lender liabilities and potential legal foes.

More sophisticated legal and financial tools have since emerged. But rather than in some stuffy Manhattan tax accountant’s office, the LLC story really begins on the frontier.

In the 1970s, an Alaskan oil company with extensive international business was looking for a way to enjoy the same limited-liability and tax benefits it received abroad and pushed the Alaska Legislature to pass laws that would allow for such investment vehicles.

The proposed bills never passed, so the Hamilton Brothers Oil Company took its policy proposal to Wyoming, where it found success in 1977. But the use of LLCs didn’t really take off until the late 1980s, when the IRS agreed to tax them like limited partnerships rather than corporations. (The latter are often subject to two rounds of taxes — one on the corporation’s income and another on its individual owner or owners.)

New York gave its green light to LLCs in 1994 after state lawmakers were convinced of the benefits they could bring to business. Almost immediately, the use of LLCs in city property sales began to rise, accounting for roughly 6 percent of all transactions and 12 percent of all commercial deals in 1997, TRD’s analysis shows.

“It gave us everything,” Saft recalled about the immediate ripple effect.

Money from the abyss

While the first U.S. laws treating corporate entities as people date back to the 19th century, the applications of that concept in New York state have expanded in ways that would have been unimaginable back then.

One big use has been political donations. Similar to real estate, campaign finance laws are designed around principles of disclosure — just as you can look up who owns a certain property in public records, you can see who donated to specific candidates and how much they gave.

But shell companies create a way to avoid true disclosure in campaign finance, as well, and real estate LLCs and political donation LLCs in New York are often one and the same. And while several bills seeking to close the LLC loophole have been proposed in Albany over the years, none have ever passed the Senate.

In New York state, corporate contributions are capped at $5,000, but every LLC can give up to $150,000 a year. And since there is no limit on the number of LLCs a person or entity can control, LLC contributions are virtually limitless.

One of the best-known practitioners of LLC donations is the developer and landlord Glenwood Management, which on a single day in July 2014 gave $400,000 to state candidates through a series of LLCs tied to its Manhattan luxury rental buildings.

The loophole comes from a 1996 decision by the state’s Board of Elections to treat LLCs as individuals. New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice and several Democratic lawmakers, including state Sen. Liz Krueger, whose district spans Manhattan’s East Side, sued the BOE in June 2017, arguing the loophole is unlawful.

An appellate court ruled against them in March, with the majority of judges on the panel saying the matter should be handled by the legislature, and the plaintiffs are now seeking to appeal that ruling.

“Corporations, basically, can’t give much at all and LLCs are allowed to be treated as individuals for donations, which I think is insane,” Krueger said. “We have tried over and over again to get that changed via legislation.”

Correction: This story was updated to clarify how Michael Dell was outed as the buyer of a $100 million apartment at One57.