Leading up to September’s primary, the real estate industry flung hundreds of thousands of dollars at two Democratic candidates for New York state attorney general: Sean Patrick Maloney and Letitia James.

Developers and landlords eventually funneled the most cash to Maloney — spurred at the 11th hour, some say, by the trajectory of the polls — but James clinched the race with more than 40 percent of the votes.

The city’s public advocate, who has clashed with property owners and their lenders over her annual “Worst Landlords Watchlist,” is now poised to become the first African-American woman to serve as the state’s top prosecutor. And though she’ll face off with Republican Keith Wofford in November’s election, she has both Gov. Andrew Cuomo and history on her side: A Democrat has held the position of New York’s AG for the last three decades.

Related: Albany’s power structure resets

One major question is what James would do as attorney general when it comes to the city’s high-powered real estate industry. That includes how the AG office’s Real Estate Finance Bureau handles review and enforcement on condo and co-op projects, as well as whether she would push for more housing regulation and tenant safeguards.

James’ press secretary, Delaney Kempner, told The Real Deal that the Worst Landlords list has only strengthened her relationship with the real estate industry, since the bulk of New York City landlords “are good and decent people” and not targets. Kempner added that, if elected, James plans to step up enforcement against money laundering and bank fraud tied to real estate.

Some industry sources say James would also uphold Eric Schneiderman’s focus on tenant protection, using aggressive litigation to tackle housing complaints. Before abruptly resigning in May amid allegations of physical assault, Schneiderman had made it a mission to go after bad-actor landlords.

“There’s no question that she’s a tenant advocate,” real estate attorney Stephen Meister said about James, adding that he doesn’t see that as a problem. “For those landlords who have been abusive of tenants’ rights, she’s going to be a problem. But, obviously, a majority of landlords aren’t in that bucket.”

Others believe her relationship with the governor — a close ally of many New York developers and landlords — could play a big role in her actions. And while James would have a good shot at freeing up resources for the AG’s office, she’d be limited in what she could do to hold individual property owners accountable.

“Litigation is a huge investment in time, energy and resources,” said Erica Buckley, a former Finance Bureau chief who’s now a

partner at the global law firm Nixon Peabody. “Is it fair to employ more than half your team on a case that isn’t a slam dunk? I think the answer is no.”

The Trump card

Before the primary, James made it clear that she would take on a leading cause for Cuomo and acting AG Barbara Underwood: going after President Donald Trump and his family’s private endeavors.

On that front, she may already have her work cut out for her. James would inherit the state’s lawsuit against the Trump Foundation, its criminal investigation into the president’s longtime fixer, Michael Cohen, and legal claims against the Trump administration on everything from labor laws to the protection of migratory birds.

When it comes to regulating New York real estate, though, James has been less vocal about what her priorities would be.

At a local forum in Harlem, she told attendees in August that her current office had “turbocharged” the Worst Landlords list and vowed to take the same level of action as attorney general. James also said that as a City Council member in 2005, she was a fierce opponent of Forest City Ratner’s Atlantic Yards megaproject, now known as Pacific Park.

“I’m the only individual on this stage that’s actually taken a major developer all the way to the United States Supreme Court and almost bankrupted him,” James said, referring to an eminent domain case she supported against the developer and state and city officials, which the court declined to hear.

That event was one of a few before Sept. 13 where she spoke candidly about the industry.

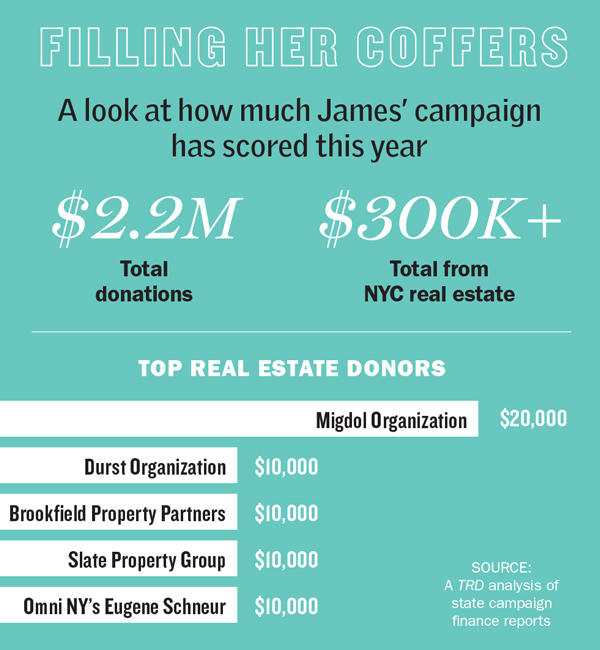

James’ campaign coffers, meanwhile, swelled with contributions from landlords and their brokers over the summer, raising $300,000 from New York real estate donors by primary day. That included contributions from two nursing home landlords who were investigated and disciplined by Schneiderman — including Allure Group’s Joel Landau. It also included money from Rosewood Realty Group’s Aaron Jungreis, who has brokered multiple deals for alleged slumlord Ved Parkash. Parkash topped James’ list with a total of 2,235 violations in 2015 and came in at fifth place the following year with 1,020 violations.

James later returned a $10,000 contribution from Landau and promised to give back contributions from two other donors with spotty records.

“There is a conflict in accepting funds from companies or individuals currently being sued by the Attorney General’s office or with recent legal matters before the office,” Kempner emailed TRD a week before the primary.

In response to additional questions in late September, the campaign spokesperson said James would work to “end vacancy and luxury decontrol” while taking on cases of “eviction by construction, deprivation of services and the fraudulent deregulation of apartments.”

But not everyone is convinced that James would be able to remain independent from New York’s real estate industry, or the governor. George Albro, a founder of the Working Families Party, helped bring James to victory in her first City Council run. Last month, however, he voted for Zephyr Teachout — the most liberal of the AG candidates, who vowed not to accept donations from real estate developers.

“The attorney general has a unique job, kind of like a watchdog on government,” said Albro, who’s now on the executive committee of the New York Progressive Action Network. “And we were concerned that if a candidate owed their election to the governor, they would be reluctant to investigate instances of corruption in his administration.”

Maloney, on the other hand, became real estate’s top pick among the Democratic candidates as the primary heated up. His campaign landed more than $490,000 from the industry by the day of the primary. And the Real Estate Board of New York urged its members to donate money to his campaign — following a Siena College poll that showed him leading by a slight margin, Crain’s reported a few days before the primary.

REBNY’s president, John Banks, told TRD that the trade group has always had a professional working relationship with the New York AG’s office, and he doesn’t anticipate that changing. His organization gave both Maloney and James $25,000.

“We’re not afraid that the AG is going to go after bad actors. In fact, we’d support it,” Banks said, noting that REBNY takes a “reputation hit” whenever landlords break the law.

Other real estate players have accused James of going overboard in tallying up landlords with hundreds — and in some cases thousands — of housing violations. In some instances, investors who bought buildings inherited the violations and weren’t given enough time to address the core problems, sources say.

Billionaire landlord Kamran Hakim filed a lawsuit against James in 2016 arguing that he was unfairly included on her list. The complaint was dismissed in May, but Hakim is appealing. His attorney told TRD that the landlord’s appeal isn’t affected by the AG race and that he “wishes only the best” for James in her pursuit.

John Catsimatidis, CEO of the Red Apple Group, said he had a good relationship with James when she was a Council member. “She was always cooperative,” he said. “When you needed permits or you had a gripe, she would listen.”

One industry player was less enthralled about the Democratic attorney general candidate.

“This woman, bad idea,” said Kevin Salmon, a founding member of the Manhattan-based commercial brokerage Khizer Property Advisors. “She sees landlords as nothing but a bunch of evildoers.”

Gavels to stamps

Overall, real estate looms large in the New York AG’s office.

The office’s legal department has five main divisions, and the industry plays a key role in three of them — the Real Estate Finance Bureau in the economic justice division, the Real Estate Enforcement Unit in the criminal division and the Real Property Bureau in the state counsel division.

The Finance Bureau oversees the development of condos and co-ops, while the Enforcement Unit pursues cases of bank fraud as well as tenant harassment and other housing issues.

The AG’s office also has authority to use the Martin Act, which regulates the sale of securities in the state and grants the office broad subpoena power. It even allows the AG to bar businesses from selling condos and co-ops in fraud and felony cases.

In other cases, the state’s top law officer can halt condo and co-op sales to force developers to fix any building defects, said Rachael Ratner, a partner with Schwartz Sladkus Reich Greenberg Atlas who focuses on condo and co-op litigation.

“It’s definitely an effective tool for the AG to force sponsors to make sure that the properties that they are delivering are what they promised,” she said. “It’s something that developers are very fearful of because it stops the money flow.”

But the office’s criminal division often relies on state agencies to grant jurisdiction before it can pursue a case, and the state’s penal laws can be restricting. In order to file criminal charges over the harassment of rent-regulated tenants, for example, there must be proof that there was intent to cause physical harm. So the AG’s office has to get creative and find other relevant charges in those cases, sources say.

A prime example is Schneiderman’s prosecution of landlords Steve Croman and Dean Galasso — both of whom were convicted of mortgage fraud rather than their alleged mistreatment of tenants.

“New York state laws are not designed to punish tenant harassment,” James’ press secretary said. “More severe and directed penalties would facilitate enforcement aimed at protecting tenants.”

At the same, the bulk of the AG’s work on real estate is more about rubber stamps than prosecutions. A perennial complaint from the industry is the complexity of condo offering plans, which can include hundreds of pages.

Doug Heller, a real estate attorney at Herrick Feinstein who worked as a top deputy to former New York AG Louis Lefkowitz, said today’s offering plans don’t provide enough transparency for the consumer. “The public wants to know what they are buying,” Heller said. “Not endless inconsequential details.”

James’ campaign said she would continue the Finance Bureau’s effort to digitize the filing process for offering plans.

Her opponent, Wofford, told TRD that he would work to move the filing process to local districts where the construction is taking place, rather than centralizing approvals for projects around the state in Manhattan.

“We have to commit enough resources in the office that we are facilitating the creation of more housing,” he said.

Who’s sold?

Time Equities founder Francis Greenburger, for one, said he thinks James is ready for the job, given her experience working for former AG Eliot Spitzer’s administration in the early aughts. That background would prove especially useful in “administering co-op and condo filings,” Greenburger said.

Some also say James could help the Finance Bureau tap its side fund of more than $4 million, which has been off limits in recent years.

The fund was created in 2008 as a way to help supplement the AG office’s budget. Despite the downturn, the office was seeing an uptick in the number of offering plans being filed, and its boss, Andrew Cuomo, was eager to crack down on defective construction. The state raised the maximum filing fee to $30,000 from $20,000 that year, with the extra money being set aside for the fund.

But the bureau hasn’t had much control over when or how it spends the money, since it’s allocated through the state budget. The AG’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment about the fund.

Buckley said the tension between Cuomo and Schneiderman — which occasionally popped up in spats over how to spend litigation settlement money — likely played a role in the bureau’s inability to control the fund.

“I think that happened because of relationships that Eric had or didn’t have,” Buckley said. “The money is there. That’s the thing that is so crazy.”

She added that James’ good relationship with the governor could bode well for the Finance Bureau. Kempner declined to comment on the fund specifically, though she said James would “use any and all opportunities to fight for increased funding for the office.”

What the Democratic AG candidate prioritizes may largely depend on what she sees as her next step.

The position has proven to be a good stepping stone to higher office, Heller pointed out, noting that the two New York attorneys general before Schneiderman — Spitzer and Cuomo — both went on to become governor.

“The office has no political opposition,” he said. “Whatever you do, you sound like a hero.”

—Additional reporting by Patrick Mulholland