For more than 50 years, the Gross and Grobman families witnessed the evolution of Clinton Hill from their Key Foods supermarket at 325 Lafayette Street. Since 1948, the families had climbed their way up in the grocery business, starting as local butchers and grocers in Brooklyn to owning a large, regional chain of markets.

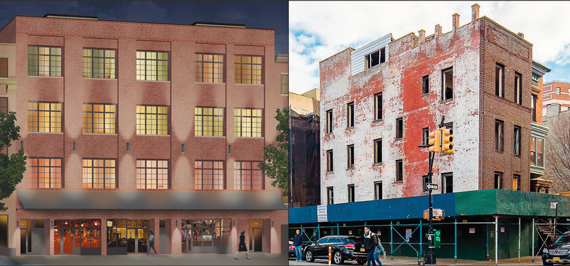

But last year, in an attempt to capitalize on skyrocketing land values, the families joined forces with Brooklyn developer Slate Property Group. They are now co-developing an eight-story, 114-unit rental building at the site, which will house a supermarket on the ground floor. Both sides declined to disclose specifics, but said the $60 million deal is a win-win.

“This was the single best way to improve our investment,” said Ira Gross, a vice president of Dan’s Supreme Supermarkets Inc., which operates under the name Key Foods.

Driven by rising property values, a lack of affordable land and property owners looking to get a slice of the windfall from development, sources say partnerships between developers and non-real estate entities are proliferating citywide.

The relationships have spawned a group of unlikely developers — from supermarket owners to cash-strapped churches to car wash owners. What these seemingly disparate entities share is what often amounts to a golden ticket in real estate — owning the right property at the right time.

Experienced real estate developers say these unlikely partners can be key to projects involving assemblages. On top of that, teaming up with these long-term property owners can also be a way to lower a developer’s equity requirement, assuming the partner contributes land to the deal.

“You’re usually capped on your loan-to-cost capital, but if your land is equity, you can borrow more on the other stuff,” said Michael Falsetta, executive vice president at commercial appraisal firm Miller Cicero. “So the idea is, it reduces the developer’s equity requirements and raises the internal rate of return.”

Out-of-reach land prices

Brokers said joint venture deals are more common when the market is frothy. And frothy it is: Citywide, land prices hit $298 per buildable square foot at the end of 2015, a 19 percent jump from 2014 and an 135 percent increase from 2009, according to data from commercial brokerage Cushman & Wakefield.

In Manhattan, land prices rose 10 percent between 2014 and 2015 to $649 per buildable square foot, while in Brooklyn they skyrocketed 37 percent during the same time to $255.

“We realized a few years ago that as land prices were getting out of control, it was hard to buy land that made sense,” said Slate co-founder David Schwartz, who added that his company has done half a dozen JV deals with longtime property owners in recent years. “Land owners in Brooklyn own at a low basis. … We can structure deals whereby they retain some or part of the real estate and can also collect their money.”

Ariel Property Advisors’ Victor Sozio said in many cases property owners “start getting calls” from developers looking for prime sites to build on.

“In a lot of cases, [these owners] don’t want to sell and be done with it,” he said. Instead, they want to “reap the rewards of a strong market.”

For example, commercial brokerage TerraCRG is currently marketing a development site with roughly 34,000 buildable square feet in Sunset Park on behalf of an owner who operates a car wash.

“Sometimes, owners don’t want to sell but they want to stay in the deal and hopefully make more money by developing it for the long term,” said Ofer Cohen, founder and president of TerraCRG.

Holy alliances

For centuries, churches have sought to reap financial benefit by strategically selling or leasing land they’ve owned. But they are increasingly showing a greater willingness to participate in the development of their land as a way to generate bigger profits.

Late last year, for example, Trinity Real Estate, the real estate arm of Trinity Church, sold a 44 percent stake in its massive Hudson Square portfolio to Norway’s sovereign wealth fund for $1.56 billion. (The church’s full real estate portfolio is valued at $3.55 billion).

At the time, Rev. William Lupfer, rector of Trinity Wall Street, said the Hudson Square deal would help “sustain Trinity’s ministries around the globe for many generations to come.”

The church is now wrapping up the planning stages of a 300,000-square-foot residential development at 74 Trinity Place, which will also house a 444-seat public school.

Similarly, Collegiate Churches of New York caught the development bug.

The church is partnering with Ziel Feldman’s HFZ Capital on a 64-story condo tower on West 30th Street in NoMad after selling three properties to HFZ for just over $70 million in 2013. Those properties were the Bancroft Building at 3 West 29th Street, 11 West 29th Street and 8-14 West 30th Street.

In 2015, the developers razed the Bancroft Building to make way for the condo, which will house programming and office space for one of its ministries, Marble Collegiate Church, currently located at 1 West 29th Street.

Feldman declined to comment and Collegiate did not respond to requests for comment.

Collegiate is also venturing into the development world on its own and converting the historic Collegiate School at 378 West End Avenue into a 66-unit residential building. (The church and school are separate entities, but Collegiate Churches bought the school site for $125 million last year.)

131-135 Alexander Avenue (left), and 99 Morningside Avenue, in the Bronx

Meanwhile, St. Luke’s Baptist Church hired Ariel Property Advisors to identify a JV partner at 99 Morningside Avenue, according to Sozio. After several months of vetting potential partners, Azimuth Development Group bought the property for $4.9 million and teamed up with the church. The partners are now planning a 22-unit condo at the site.

But Sozio said not all property owners who start out thinking they’ll bring in a developer and stay on the project actually see it through fruition.

“In close to 50 percent of those times,” he said, “it ends up being an outright sale.”

Buy and hold investors

Among commercial land owners, individuals or firms that might have previously elected to lease or flip long-held properties are also being lured into the development game. Related Cos. paid Ponte Equities — a firm owned by the Ponte family, which bought parking garages, warehouses and auto shops in Tribeca in the 1960s — $115.3 million in 2013 for a six-parcel development site in Tribeca. Now, Related and Ponte are developing a 46-unit condo at 261 Hudson Street, the site of the former Ponte family restaurant, and 70 Vestry Street, a planned 47-unit condo. The two are also partnering on 456 Washington Street, a 107-unit rental building.

According to Sozio, JV deals are particularly common in emerging markets where landowners may have owned a warehouse or industrial site for years.

That was the case with Yates Restoration, a family-owned company that restores building facades. JCAL Development bought a development site at 131-135 Alexander Avenue in the South Bronx, right next to a small lot that Yates owned and used for storage at 131-133 Alexander. JCAL brought Yates into the deal — a move that allowed it to use both sites. They are now planning a nine-unit rental.

“We always hoped that 131-133 Alexander would get developed, as well,” said JCAL’s Billy Bollinger. “Not only was it a vacant lot but it also had a forklift going in and out sporadically,” he said, referring to Yates’ storage business.

At 325 Lafayette, the Gross and Grobman families proactively pursued a development partner, Gross said.

“We didn’t think about cashing out,” he said. “We knew this property was a really wonderful site in this up-and-coming Brooklyn market.”

For Slate, working with non-development partners has become a new source of business. In addition to 325 Lafayette, Slate is partnering with the longtime owners of 66 Ainslie and 21 Powers Streets in East Williamsburg, who operated plumbing and boiler businesses at the sites. In 2014, Slate paid $21 million for the pair of properties, but the property owners, officially known as Tavolario and Meszaros Realty Corporation, left an unspecified amount of equity in the deal. The partners are developing a 50-unit rental at 66 Ainslie and a 10-unit condo at 21 Powers.

When to say no

Although the lure of development can be strong, it’s not a business for everyone — and there are risks for inexperienced partners.

For example, JV deals are common in areas that are about to be rezoned but those deals carry risk if the rezoning doesn’t come through.

“It can take years to get zoning and variances,” said Dan’s Supreme’s Gross. “You’re gambling.”

TerraCRG’s Cohen said he advises owners to become equal partners with developers to protect their interests. “In the old days, people would come to unsophisticated owners and say, ‘You put up the land, I’ll finance the project,’ but [the developer] would not put any equity in of their own,” he said.

Similarly, Sozio presses property owners to clearly state their requirements from the outset to ensure they get a fair shake. At 99 Morningside, for example, the church wanted a new sanctuary and office space.

Still, at the end of the day, not all deals make sense.

“On some of our sites, we’ve had opportunities for a long time, and we just never nailed a deal because it’s so complicated,” Gross said.

Last May, the Gross and Grobman families sold a property at 4525 Eighth Avenue in Sunset Park for $15.8 million because they simply could not work out a profitable deal for themselves. After doing the math, Gross said he projected negative cash flow for 25 years under a best-case scenario. “We tried so hard. We spent a lot of money on studies, architectural reviews and engineering,” said Gross. “We’re not sellers, but we just couldn’t find any competitive edge to develop.”