Harry’s Bar — tucked away on the second floor of the Park Lane Hotel — isn’t the sexiest place for a nightcap. Narrow and dark, it has heavy wood paneling and low lighting, with no hint of the building’s dazzling Central Park views. On a recent weeknight, an anemic crowd sat nursing drinks mostly in silence as an episode of “Jeopardy!” flickered across a flat-screen TV.

It’s hard to imagine the hard-partying Malaysian billionaire Jho Low ever had anything to do with the place.

But according to federal prosecutors, Low’s investment in the Park Lane was part of a massive scheme to defraud a development fund in his home country out of $4 billion. And in 2016, the U.S. government moved to seize the 47-story hotel — where a prominent investment group led by developer Steve Witkoff had planned to build a posh condo tower. It also seized a condo at the Time Warner Center, a London penthouse and an estate in Beverly Hills in an attempt to recoup some of those allegedly stolen funds.

For years, law enforcement has used “asset forfeiture” to punish criminals and compensate their victims. In the years following Sept. 11, forfeitures skyrocketed as prosecutors sought legal remedies to keep terrorism financing out of the United States.

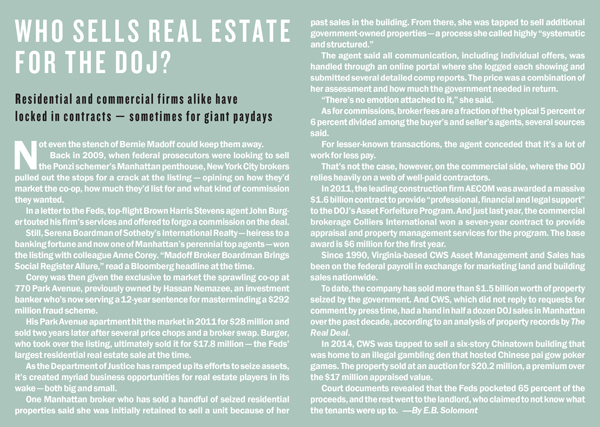

In some of the best-known forfeiture cases, the government liquidated the assets of Ponzi mastermind Bernie Madoff, “kleptocrat” Taiwanese president Chen Shui-bian and hip-hop producer (turned cocaine trafficker) James Rosemond.

But with the Park Lane — valued around $1 billion — the stakes are infinitely higher, and the hotel is just one of two massive properties in the government’s crosshairs. This past July, a federal jury decided that the U.S. government can seize 650 Fifth Avenue, which sits in a prime Midtown location at the edge of Rockefeller Center on 52nd Street.

Prosecutors are also seeking forfeiture of tens of millions of dollars of residential real estate owned by Paul Manafort, President Donald Trump’s former campaign manager. An indictment against Manafort in connection with the current Russia investigation cites several properties in New York and Florida, including a condo at Trump Tower in Manhattan, a brownstone in Park Slope in Brooklyn and homes in Bridgehampton and Palm Beach Gardens.

But the Department of Justice has had a spotty record when it comes to real estate — including bungled sales and mismanaged properties. And these latest cases are raising questions about whether it’s out of its league.

The Park Lane Hotel, where Jho Low owned a majority stake

Early on, the inexperience of the U.S. Marshals Services, which oversees the management and sale of real estate for the DOJ, led to a “lot of mistakes,” according to David Smith, former deputy chief for DOJ’s Asset Forfeiture Program (AFP), who now runs a private law practice. “They have improved,” he said. “[But] they’re still not getting fair value for the real estate in a lot of real estate fields.”

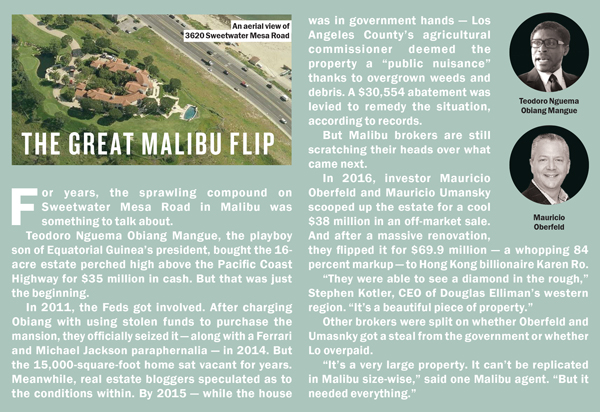

In 2016, for example, the DOJ sold a seized Malibu estate for $38 million — only to see the buyers flip it for $69.9 million a year later.

Some noted that the agency just isn’t interested in keeping major assets on its books. “Everyone knows it’s a distressed sale,” said Peter Henning, a law professor at Wayne State University in Michigan who studies white-collar crime. “The government needs to get rid of it,” he said. “They want to get the money and move on; they don’t want to make victims wait two to three years.”

As the government has gone after corruption and money laundering, real estate is increasingly a DOJ target because it’s vulnerable to shady practices, said Laura Marshall, a former prosecutor who is now a partner at Hunton & Williams in Virginia.

“We’ve seen more focus on real estate being the subject of forfeiture because of all the information we’ve been receiving showing that real estate is at high risk for money laundering,” Marshall said.

A civil action

Since the 1970s, the DOJ has used asset forfeiture to fight crimes ranging from money laundering to drug trafficking. The basic premise of the program is to seize cash, art, jewelry or real estate purchased with ill-gotten gains and use the proceeds to repay victims and help fund law enforcement.

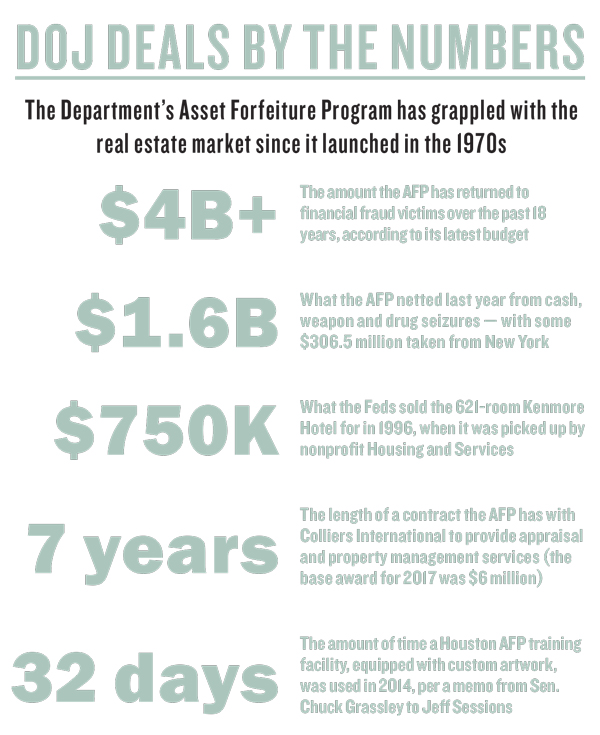

Since 2000, the agency has returned $4 billion-plus to victims of financial fraud, according to the AFP’s fiscal 2018 budget, which estimated that the program would generate $1.98 billion in revenue this year.

According to the Institute for Justice — which advocates limiting the size and scope of government — the DOJ seized 5,540 properties nationwide valued at $1.2 billion between 2008 and 2016, including 304 properties valued at $188 million in New York State. The program netted $1.6 billion from cash, weapon and drug seizures in 2017 with some $306.5 million from New York, according to the AFP.

“Asset forfeiture can be unbelievably harsh; make no mistake, it’s a punishment,” said Sharon Cohen Levin, former chief of the Money Laundering and Asset Forfeiture unit at the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York.

“But while it can be harsh, it has important compensatory results,” added Levin, who’s now a partner at the law firm WilmerHale. “It can be used as an important means of providing compensation to victims.”

However, the program isn’t without critics.

Forfeiture takes two forms — criminal and civil, the latter of which has been a lightning-rod issue in recent years.

In criminal cases, federal prosecutors can seize a property only after a conviction if they can prove that the money used to buy it was dirty.

Civil forfeiture, however, offers something of an end run around that. It requires no criminal charges and allows the government to bring an action against a property (think USA vs. Luxury Condo.) And the DOJ has capitalized on that loophole.

“The reason why they go often to the civil forfeiture tool is because it’s easier to prove,” said Evan Barr, a former assistant U.S. attorney for the Southern District who is now a white-collar defense attorney at Fried Frank. “A criminal case requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt — a much higher standard.”

Low thresholds, critics argue, have given law enforcement too much power to seize cars and cash from innocent people. Under President Barack Obama, the DOJ rolled back so-called adoptive forfeiture, which allows police officers to take property from suspected criminals without approval from a judge. But the Trump administration has taken the opposite tack.

Politics aside, prosecutors have increasingly used civil forfeitures to go after white-collar criminals.

Levin acknowledged the program gets a “bad rap,” but she insisted it’s been crucial in cases where criminal convictions are not possible.

In 2011, for example, her office filed a claim against now-defunct Lebanese Canadian Bank, based in Beirut, for its role in a complicated scheme involving used cars, the West African drug trade and money laundering by Hezbollah, which is considered a terrorist organization by the U.S.

“It was something where there weren’t people to criminally prosecute,” Levin said. “The participants in the U.S. were bit players.”

In 2013, the U.S. Attorney’s office announced a $103 million settlement with the bank — proceeds of which Levin said went to a government task force.

650 Fifth Avenue

Similarly, Levin’s team went after 650 Fifth — a 36-story office building owned by an Iranian charity, the Alavi Foundation. In June, a jury determined that the foundation is controlled by the Iranian government. The verdict gave prosecutors the green light to seize the property, which throws off millions of dollars in rent each year in violation of U.S. sanctions against Iran.

Levin said proceeds from any eventual sale of the building — reportedly valued around $500 million — would be distributed to victims of Sept. 11 and other terrorist attacks.

“There was unbelievable interest,” she said of the property. “It’s an expensive piece of real estate in a prime location.”

For that reason, how the DOJ handles it will be closely watched in real estate and legal circles. A lucrative deal would be a huge win for prosecutors. But anything less than that could leave hundreds of millions of dollars on the table. And worse, it would send the message that even though the DOJ has grown more ambitious in its mission to crack down on corruption and financial crimes, it’s not prepared to deal with the most valuable properties involved in the criminal schemes it uncovers.

The DOJ declined multiple requests for interviews. “Department guidelines are designed to assure properties are sold on commercially reasonable terms,” a spokesperson said via email.

That means “open market, arms-length sale at fair market value using qualified and approved brokers,” the spokesperson added.

One early test of civil forfeiture took place in 1994, when the Feds seized the Kenmore Hotel — a seedy, 621-unit, single-room occupancy hotel on 23rd Street that was a hub for drug trafficking. At the time, the building was owned by a Vietnamese shipping magnate Tran Dinh Truong, who allegedly turned a blind eye to the squalor and crime under his nose.

“You’d see a guy mopping and … the water would be so thick with black dirt that he’d end up making [the floors] dirtier,” recalled Scott Kimmins, a former New York Police Department officer whose precinct coordinated with the DOJ on arrests in June 1994.

But the Kenmore also became a cautionary tale for the Marshals Service, which was then inexperienced when it came to managing tenants. “The U.S. Marshals Service became the landlord, basically, and that was kind of an awkward situation, because at least back then they had precious little experience in the real estate arena,” Barr said.

Eventually, the Feds brought in a new management company, but not before tenants, facing eviction over unpaid rent, sued and claimed that the government had failed to control drug-dealing and prostitution there.

In 1996, the nonprofit group Housing and Services bought the property for only $750,000.

Over the past two decades, law enforcement has refined its processes, sources said.

And the program has greatly expanded since 2000, when Congress broadened the parameters of civil asset forfeiture to include money laundering and other financial crimes, such as public corruption and wire fraud.

“When I first started as a prosecutor in the Southern District [in the early 1990s], it was not routine to even seek forfeiture as part of a criminal case,” said Barr. “Now in almost every criminal case, whether it’s white-collar or drug-related, there is a forfeiture count included in the indictment.”

But the marshals’ track record is mixed.

Take the Bicycle Hotel and Casino in Bell Gardens, California, which the Feds took over in 1990 after declaring it was built with $12 million in illegal drug money. The casino remained a haven for criminal activity under the government’s tenure, and by the time it finally sold in 1999, annual profits had plummeted to $4 million from $23.4 million, according to the Los Angeles Times.

“It was a disaster for the marshals,” said Smith, the former deputy chief of the Asset Forfeiture Office. “It attracted the attention of Senate investigators.”

Can someone say slush fund?

Last September, Sen. Chuck Grassley, a Republican from Iowa, blasted the Marshals Service for turning money recovered through asset forfeiture into a “slush fund.”

“There are laws governing the use of this money for a reason,” he wrote in a September letter to Attorney General Jeff Sessions accompanying a 15-page memo, outlining how the marshals allegedly used recouped cash for swanky office renovations and other frivolous expenses.

“Playing games with unappropriated funds to avoid accountability is outrageous and cannot be tolerated,” wrote Grassley, who has argued for better oversight of the program’s finances.

The memo cites an asset forfeiture training facility in Houston, Texas, that was outfitted with high-end granite countertops and custom artwork. The facility was used for just 32 days in 2014. Last year, it was booked for only 52 days.

The Institute for Justice noted that allowing an agency that seizes assets to then add that money to its own budget creates an environment ripe for abuse.

“No one is checking line-item expenditures,” said Jennifer McDonald, a research analyst at the institute, citing a Texas district attorney who bought a margarita machine with money seized through civil forfeitures.

A copy of a forfeiture training manual used by the Department of Homeland Security, which was leaked this past fall, included a dozen pages describing how agents should turn to real estate experts and commercial property databases to appraise real estate and avoid wasting time on “liabilities” — properties not profitable enough to make it worth their time.

“The mission is supposed to be stopping criminal activity,” said McDonald. “They’re telling people, ‘We have a profit incentive here. If it’s not worth our time, we’re not going to take it.’”

The Marshals Service’s Complex Asset Team is one division that’s come under heavy fire for mismanaging sales and for cronyism. The team, which handles the most complicated cases, was involved in seizing assets from Madoff as well as Marc Dreier, the notorious lawyer serving a 20-year sentence for a $400 million Ponzi scheme, and Hassan Nemazee, an investment banker convicted in a $292 million fraud scheme.

In 2010, an employee at Forfeiture Support Associates — a DOJ contractor — filed a whistleblower suit accusing the team’s chief, Leonard Briskman, of flouting conflict-of-interest rules. According to the whistleblower, Briskman frequently failed to market assets widely and routinely found buyers for forfeited property through his own “business contacts.”

The claim triggered an investigation by the DOJ’s Office of the Inspector General, which confirmed the findings and documented the team’s shoddy record-keeping and failure to conduct adequate market research to value assets properly. Briskman was later reassigned.

But as recently as 2015, other whistleblowers were sounding the alarm.

In August of that year, Grassley took to the Senate floor with a fiery critique of the Marshals Service for allegedly retaliating against those whistleblowers.

In at least one case, he claimed, the service seized personal property from someone it thought was leaking information to his office and to the press. “If the Justice Department and the Marshals Service think I’m just going to go away or give up on this, then they’re even less competent than I feared,” said Grassley.

One area that Grassley didn’t address is the DOJ’s actual real estate track record.

Una Dean, a partner at Fried Frank who was a prosecutor in New York’s Eastern District from 2010 to 2017, said liquidating real estate is particularly complicated for the DOJ, which has a limited scope when it comes to cap rates and other market indicators.

“There’s always a little bit of hesitancy and more calculating that goes into ‘Should this property be seized? What’s the equity in it? How long are we going to have to hold it, what can we sell it for?’” she said.

Over the years, the DOJ has earned a reputation for underselling.

When federal prosecutors were liquidating the Madoffs’ homes in 2009, that was almost unavoidable. The market was in free fall, and there was the massive Madoff stigma to overcome.

“It’s a very small world, so you can’t hide that you bought Bernie’s penthouse,” said one residential broker on the condition of anonymity, referring to Madoff’s pad at 133 East 64th Street. “What made it more complicated was that it’s a co-op, and not an easy co-op.”

After six months on the market, Patsy and Alfred Kahn plunked down $8 million for the apartment. But just four years later, the Kahns — in the middle of a divorce that landed them on Page Six — sold it for $14.5 million.

The Corcoran Group’s Greg Kammerer, who represented the Kahns, recalled that his clients felt good that proceeds went to Madoff’s victims. “It was justice being done with the sale of this property,” he said.

But other industry players criticized the handling of the sale, with one broker saying the “government sold it for a song.”

Likewise in 2009, the government auctioned Dreier’s One Beacon Court condo for $8.2 million — a discount from the $10.4 million he paid in 2007.

And former money manager Ken Starr’s triplex at Lux 74 on the Upper East Side sold at a 26 percent discount in 2012 after the Feds seized the condo — where the Ponzi schemer (not to be confused with the independent counsel who investigated the Clintons in the 1990s) was found hiding. The apartment fetched $5.6 million at an auction, two years after Starr paid $7.6 million in a down market.

“What we got was really a steal,” said the Level Group’s Dudi Silberberg, who represented buyer Ofer Tal.

But Silberberg — who said the condo is probably worth $10 million today — recalled that the auction was poorly advertised, and that he just happened to stumble upon the notice of sale. The same can’t be said for a sprawling Malibu estate the marshals seized from Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, playboy son of Equatorial Guinea president Teodoro Obiang, who was accused of buying the house with stolen funds. Without putting the 15,000-square-foot house on the market, the government sold the property for $38 million to investor Mauricio Oberfeld and Mauricio Umansky, co-founder of luxury brokerage the Agency. They gutted the mansion and flipped it for $69.9 million last year, leaving local brokers divided on whether the DOJ undersold the estate or if the latest buyer paid through the nose (see sidebar).

“Even $30 million is a good number on the wrong side of Pacific Coast Highway,” said one prominent Malibu broker, referring to the less-than-ideal location.

“But it’s hard to think anything, because it just wasn’t made available,” the broker said. “Most people who want to get the highest and best number — especially when the variable can be great — you want to put it on the market and see what it bears.”

Trial and error

Still, bungled sales — like the Madoff assets and Bicycle Hotel — are less common these days, according to several sources.

Levin said that over the past 18 months, the DOJ has made significant changes to the program. In October, shortly after Grassley sent his letter, Sessions ordered a watchdog to review the department’s policy and make changes if needed.

The DOJ also renamed (or rebranded) the unit — from Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering to Money Laundering and Asset Recovery — to emphasize its role in compensating victims.

Rebranded or not, the agency still struggles with managing active businesses.

“You’re afraid you’ll be accused of not having run it properly — especially if it’s an ongoing business that would not be solvent but for the criminal activity,” said Stefan Cassella, a former chief of the Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering division in the U.S. Attorney’s office in Maryland.

He cited a hypothetical strip club as an example. “The marshals look at it and they say, ‘The only way this place has a positive balance sheet is because they were running prostitution out of the back room, and we are not going to allow that to happen,’” he added.

In a real-life but less fortunate case, the DOJ allegedly left a $1.3 million airplane in such poor condition after being in the custody of the Marshals Service that an insurance company declared it “totaled.”

Gerry Sachs, a partner at law firm Venable, said that when he worked as a Georgia prosecutor, he once had to manage a string of chicken restaurants pending a court-ordered sale. “That is to make sure the business or property can be sold at a fair market value,” he said.

But chicken restaurants and strip clubs are small beans compared to the Park Lane and 650 Fifth — the latter of which has already dragged on for years.

At 650 Fifth, Alavi appealed the June verdict but was rebuffed by a judge in September. It is now appealing again, more than eight years after the Feds opened the case.

Stephen Kessler, who has represented terrorism victims in the 650 Fifth case, said he typically pushes to get a court-appointed receiver at any income-producing property he’s involved in that’s facing forfeiture.

“The receiver is the one who is going to be dealing with the property, maintaining the property, and although the receiver certainly does get paid, at least you know the million-dollar property is going to be a million dollars at the end of the case,” he said. “I’m not going to leave it to the marshals to make sure of that.”

Meanwhile, Kessler also represents Melisa Singh, a professional poker player, in another forfeiture case against the DOJ.

In 2008, a 27-year-old Singh paid $775,000 in cash for a one-bedroom condo at the Moinian Group’s new Atelier on West 42nd Street. But most of the money was gifted to her by David Nicoll, a suitor who was later pinned as the mastermind of one of the largest medical bribery schemes in U.S. history.

In 2013, the apartment was listed for forfeiture. Singh has been fighting the Feds for years, arguing that the title was in her name and that the forfeiture order was not carried out properly. After losing in appellate court, she filed a petition with the U.S. Supreme Court in February.

Back-channel negotiations?

For the Park Lane, it all started in 2013, when a group of investors led by Witkoff teamed up with Low to buy the Billionaires’ Row hotel from the estate of Leona Helmsley.

Even as Low was allegedly siphoning money from the Malaysian development fund dubbed 1MBD, he agreed to finance 85 percent of the $654 million purchase, according to court documents.

After moving to seize Low’s assets July 2016, federal prosecutors turned to Witkoff to help liquidate Low’s stake in the Park Lane. Once it was sold, the government would return Low’s allegedly stolen funds to 1MDB, according to the arrangement, which a judge approved in May.

Why Witkoff? In court documents, the DOJ’s lawyers cited the “complex” nature of the property, which required ongoing cash infusions and had a limited buyer pool.

Former prosecutors further speculated that the DOJ was under pressure to “get it off the books, get what we can and get the money back to Malaysia,” said a former prosecutor who is now a partner at a large law firm. Though law enforcement is generally “paranoid” when it comes to enlisting help from civilians for fear of getting ripped off, he said, the complexity and value of the Park Lane likely changed the calculus.

In making their case to the judge, the DOJ also said that unless it began marketing the property, the assets would face “default, loss of financing arrangements and foreclosure.”

But even if it wasn’t realistic for the marshals to sell the Park Lane itself, not everyone was pleased.

In February 2017, Low’s family, which has a stake in the investment, filed documents objecting to Witkoff’s role in the sale. Granting the developer that kind of authority “would provide Witkoff with the opportunity to enrich itself” to the detriment of the Park Lane’s investors, they wrote in court documents.

Their objection fell on deaf ears, and in May Witkoff enlisted Eastdil Secured to sell the hotel for around $1 billion.

But over the summer, the DOJ shifted gears and asked the court for a stay in the civil forfeiture as the FBI’s criminal investigation of Low began to heat up.

Then in November, when bids were due, no one showed up.

“There was nothing acceptable,” said Howard Lorber, whose New Valley has a 5 percent stake in the project, according to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filings. “The marketing effort was to see if there was a buyer that would be acceptable.”

Some chalked that up to the soft luxury market, but others said the marketing was bungled.

“It’s too easy to blame the high-end condo market for why they didn’t get good traction,” said one prominent investment-sales broker. “This is not your generic high-end property. This is as good as it gets.”

Eastdil declined to comment, but sources close to the firm said it is still advising Witkoff. The developer also declined to comment, but told the New York Times in 2017 that “this was the best site in New York City and maybe the world.”

“We designed what the entire partnership thought was a beautiful building,” he said. “Little did we know we’d face circumstances like this.”

One former federal prosecutor speculated that Witkoff is negotiating with the government through back channels to sell Low’s stake to the current investors — or a third party.

“I’m not sure anybody is interested in selling it,” the prosecutor said.

For the Marshals Service, there’s little to no upside to forfeiture if they have a fair-market value offer on the table. “It’s not the Marshals’ business,” the prosecutor added. “In the end, there’s only criticism if the Marshals don’t sell it for enough money. It’s easier to just get cash.”