Forty-five minutes into a mostly restrained interview, Ardie Tavangarian reached into his right pocket, pulled out a sturdy black cellphone and placed it on the gorgeous mango wood table between us. The developer hit play on a saved audio message, and the baritone voice that entered the room — notably raspy and impossibly enthusiastic — was unmistakable.

“Ardie, you’re just such a superstar — congratulations brother!” Tony Robbins began, the self-help guru’s monologue coming fast and breathless. “I love you so much. I’m so proud of what you built and how you built it, with such elegance and such integrity, and you do things at just an incredible level of quality. I can only imagine what you’re going to do to these homes and how you’re going to transform them.”

Robbins left the voicemail early this year, soon after Tavangarian had closed on one of the splashiest deals of his career: the four adjoining Bel Air properties Elon Musk was offloading as he famously bolted for Texas.

Tavangarian became friends with Robbins decades ago, the developer said, after he renovated Robbins’ early 20th-century Spanish-style castle in Del Mar, a home that Robbins later sold for $2.1 million in 1997. The two have also traveled together, and Tavangarian recently invited Robbins to stay in one of his properties.

The connection may seem odd — Tavangarian, silver-haired, short and stout, is soft-spoken and discreet, a near perfect inverse of Robbins’ larger-than-life, fire-walking stage presence — but the developer credits his friend Tony, particularly his teachings on environmental psychology, with influencing his own career.

Robbins, Tavangarian said, “helped me become more focused on people versus the dollars.”

The friendship also offers rare insight into who Tavangarian actually is. In a career that’s spanned four decades, the 63-year-old founder of West Los Angeles-based Arya Group has developed dozens of ultra high-end projects, including residential homes, public works and resorts.

Recently, he’s also built and sold some of the most spectacular — and expensive — houses Los Angeles has ever seen, including a Bel Air mansion that sold for $75 million in 2019 and a Pacific Palisades mansion that sold for $83 million in July.

He promises to transform the former Musk properties, which he acquired for a combined $62 million, into a sustainability-oriented, humanity-advancing project worthy of the association with the SpaceX founder.

An architect by training, Tavangarian has worked with Frank Gehry and Richard Meier. His properties have been tied to such stars as Elizabeth Taylor and Jackie Collins and moguls such as Jeffrey Katzenberg and Peter Morton.

In July, he was photographed alongside Jennifer Lopez, who toured the site of a new project. Some of his recent works have even achieved their own celebrity status: An Architectural Digest video of his Sarbonne Road mansion racked up nearly 20 million views.

Yet Tavangarian himself has remained mostly unknown, which suits him just fine. He rarely gives interviews and is quite happy to let his work do the talking. But L.A. developers who can command north of $50 million for their projects constitute a very small tribe, and his understated persona stands in sharp contrast to the frequent headlines and controversies generated by a few of his notoriously bombastic contemporaries.

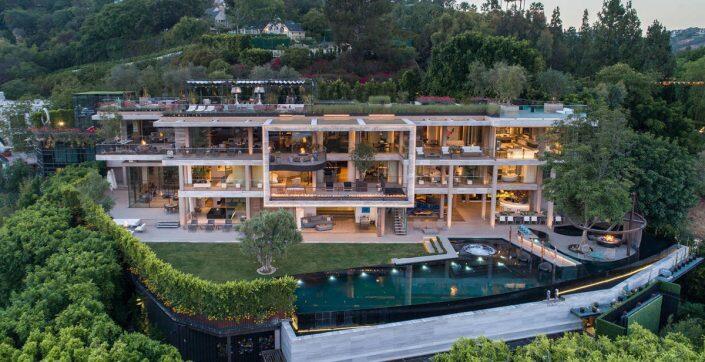

822 Sarbonne Road, Bel Air

“He’s always been a gentleman,” said Stephen Shapiro, the co-founder of Westside Estate Agency, who first worked with Tavangarian some 20 years ago. “Very gracious, very well mannered, not aggressive like some of these developers. He doesn’t threaten. He does his work, does his product, and then lets his product speak for itself.”

“Never heard of him,” said another prominent luxury Westside broker.

The kite runner

Decades before he was quietly building California dream homes for A-listers, Tavangarian was fascinated by kites.

The son of a military judge, he grew up in the Iranian city of Shiraz, a provincial capital known for its wine and literary history. Iran was enjoying a petroleum-fueled economic boom in the 1960s and early 70s, and Iranians were rapidly embracing Western-style culture and consumerism.

But a young Tavangarian still had to make his own toys. He spent hours jury-rigging scooters and fastening airplanes out of styrofoam and rubber bands. He’d devise homemade kites out of thin paper and bamboo, attaching a candle on the inside so the toy would light up the night sky like a flying lantern.

“The vision of creating things — you know, it’s always been natural,” he said.

Tavangarian moved to Battle Creek, Michigan, as a high school exchange student. While taking classes at the University of Michigan, he met his wife, Tania, a Tehran native and broker who’s long served as Arya’s CFO. The couple have four daughters, two of whom work as brokers at Williams and Williams Estates Group. (The brokerage is headed by power couple Branden and Rayni Williams, who have represented Tavangarian’s properties, including the Pacific Palisades mansion.)

Tavangarian moved west in his early 20s to attend the Southern California Institute of Architecture, the now-acclaimed design school that had opened just years earlier and was then operating out of a rented Santa Monica warehouse. “We actually built the school,” Tavangarian said. “And I was basically living under a drafting table.”

He founded Arya at the age of 22, initially running the firm from a tiny space inside a parking structure in order to tout a coveted Beverly Hills address. The location paid off: The young designer, a devotee of such icons as Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright, did some work for the property’s landlord, who subsequently hired the starchitect Richard Meier. Tavangarian submitted sketches.

“And then we click,” he said of Meier, “because I knew his discipline better than a lot of people in his own office.” Tavangarian was soon hired to build the Meier-designed Norman and Lissette Ackerberg House, an all-white contemporary mansion in Malibu’s Carbon Beach. (In 2017, Oracle boss Larry Ellison bought the 7,700-square-foot home for $48 million.)

It was Meier’s first Southern California project — and Tavangarian’s big break. Arya went on to work on other projects with Meier, including galleries at the Getty Museum. The firm also led major hospitality projects, including the redevelopment of the Bernardus Lodge, in the Carmel Valley, and Hotel Maya, in Long Beach. It managed construction of the Freedom Sculpture, the glittering statue in the middle of Santa Monica Boulevard that was unveiled in 2017 as a gift to Los Angeles from the Iranian-American community.

It was Meier’s first Southern California project — and Tavangarian’s big break. Arya went on to work on other projects with Meier, including galleries at the Getty Museum. The firm also led major hospitality projects, including the redevelopment of the Bernardus Lodge, in the Carmel Valley, and Hotel Maya, in Long Beach. It managed construction of the Freedom Sculpture, the glittering statue in the middle of Santa Monica Boulevard that was unveiled in 2017 as a gift to Los Angeles from the Iranian-American community.

Some 75,000 people attended the groundbreaking, including Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti, who called the sculpture a “testament to the values we hold dear.”

For Jackie Collins, Tavangarian designed a 25,000-square-foot white modernist home, which was based around an image of a pool in a David Hockney painting.

“It took a while to capture these measurements and work with Ardie on the details,” the novelist told the Wall Street Journal in 2014. “Everything came out perfectly.”

Skirmishes

Not every client has been so enamored.

In 1996, Cher, looking to build a house in Malibu, hired Arya for $4.2 million, according to a complaint filed by the firm, but the relationship subsequently turned ugly. Cher terminated her agreement with Arya, according to the complaint; the firm also accused the singer and her affiliates of misappropriating their design plans and spreading “false and damaging rumors,” including that “Arya and its principals were thieves, wrongfully abandoned a job, breached contracts’’ and presented dishonest bills.

Arya sued for breach of contract, and a California appeals court eventually ruled that Arya could enforce its claim.

More than a decade later, in 2013, the developer was in contract to buy wealthy adman Jack Roth’s Pacific Coast Highway property for $20 million. Tavangarian intended to develop the property and had already begun construction when his lawyer sent a letter terminating the contract, citing an improperly installed pool, only to then propose that Roth enter into a new sales agreement, at a lower price, and come on as a development partner.

“In case you weren’t sure, Ardie and Faryan” — Faryan Afifi, Tavangarian’s lawyer — “are shameless,” Alexander Kargher, Roth’s lawyer, wrote in an email to his client. “After having wrongfully ‘terminated’ the deal three times now, they now want you to get into business with them. “Welcome to Iran,” an irate Roth responded. Tavangarian then imposed a mechanic’s lien to assert control over the property. The parties fought in court for years, eventually reaching a settlement.

But by and large, Tavangarian, according to several industry sources, has engendered a reputation as a quiet, hyper-focused, gifted developer.

“He’s a very nice man,” said Mauricio Umansky, the founder of The Agency. “He’s a very detail-oriented human being — he definitely has a little bit of ADD, as I think most incredible men do. But he’s just talented, he’s creative, and I think he’s a good guy.”

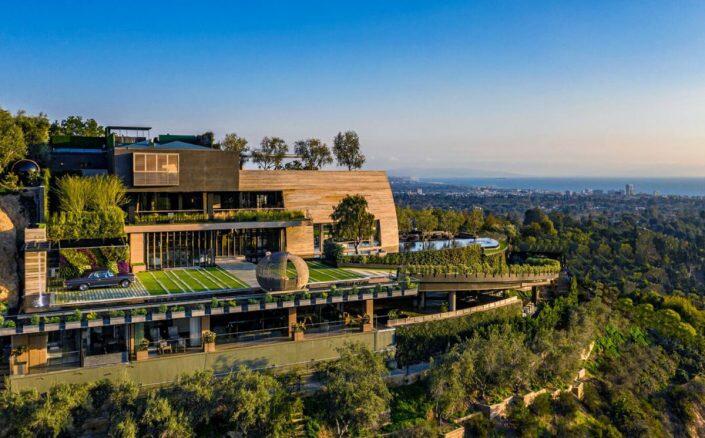

1601 San Onofre Drive, Pacific Palisades

“He’s an artist as much as he’s a businessman,” added Santiago Arana, a high-end specialist at The Agency who’s known Tavangarian for 15 years. “His motivation is to materialize what’s in his head and deliver that to whoever’s going to be the owner of those projects. Whatever comes with that — the money, the fame, and everything else — is secondary to him.”

A few years ago, Arana was at the Los Angeles Convention Center to attend “Unleash the Power Within,” a signature four-day Robbins seminar that draws rapturous crowds of more than 10,000. He bumped into Tavangarian in the VIP section. “That’s really what makes a difference,” Arana said. “You can never think that you know enough.”

Barefoot luxury

Later that afternoon, after the interview, Tavangarian meandered his black Range Rover through traffic and into the gated hills of Bel Air. The developer wanted to show off another project, on Bellagio Road — the same site recently toured by J.Lo in a visit that caught the attention of the New York Post.

The property was, essentially, a construction site, with loops of wire hanging from exposed ceiling beams and floors covered by tools and construction materials. Outside, a loaded forklift was parked near a massive dirt pile.

But Tavangarian already saw his creation coming to life. For half an hour, limping because of an Achilles tendon issue, he moved through one empty space after another, pointing out the cigar room, the chef’s kitchen, the multi-story water and fire feature. On the second floor, Tavangarian stopped next to another section of unfinished wood. It was a bar, he said.

“It looks like something from the 1920s in France, but in a modern way. It’s almost like the guy was wearing — you know in ‘Casablanca,’ the white tuxedo?”

Up a nearby hill, within view, was a 24,000- square-foot mansion completed by the developer Nile Niami in 2018. That property, originally listed for $65 million, only recently sold for a steeply discounted $36 million. “And we’re probably completely blocking their views,” Tavangarian quipped.

Luxury spec development is a high-margin but notoriously risky enterprise, where even a single failed project can end up costing its developer tens of millions of dollars. Niami and Mohamed Hadid, who has also been battling a litany of legal issues, have both recently been forced to place projects in bankruptcy; in March, Hankey Capital, which loaned Niami $82.5 million to build “The One” — the developer’s white whale, a 100,000-square-foot Bel Air megamansion that Niami once hinted would list at $500 million — served a notice of default in an attempt to force a sale. No buyer appears to be in sight.

Tavangarian has, so far, managed to avoid a similar fate. He bought 822 Sarbonne Road, the Bel Air mansion, out of bankruptcy for $11.1 million in 2014, then took on financing that included a $16 million construction loan from West Hollywood-based First Credit Bank, a frequent lender.

In 2019, Tavangarian sold the mansion for $75 million. He bought 1601 San Onofre Dr, in Pacific Palisades, for $7.3 million in 2013, then took on $27 million in construction loans from Boston Private and refinanced with a $52 million bridge loan from First Credit Bank. He initially put the home up as a “ride out the pandemic in style” luxury rental asking $350,000 a month, then sold the completed project in July for $83 million, an area record.

“Everybody thought this was an easy thing,” Tavangarian said of L.A.’s recent luxury spec home construction boom. “Just go buy a property, hire different people and they come into it, and you know, you make a lot of profit at the end. What is the message of the universe? It doesn’t work that way. You have to be really delivering.” He noted that over the past few years, four different properties he’d developed for clients have sold for north of $100 million, including a Meier-designed Carbon Beach home that Hard Rock Cafe founder Peter Morton sold in 2018 for a record-breaking $110 million.

If Tavangarian represents a kind of antithesis to Niami— who has said he considered starring in a reality show and that he built “The One” in order to “create the biggest, most expensive house in the urban world” — Tavangarian’s projects also present a sharp contrast to the “white box” megamansions that became commonplace around L.A. over the last decade, industry sources said.

His central obsession is creating connections with nature: He changed the whole design of the Bellagio Road development to preserve a mature oak tree, he said, and is creating a retractable roof feature inspired by the hot summer nights of his childhood, when families would sleep outside on flat roofs to stay cool.

He also emphasizes that his homes elevate warmth and comfort over visual splendor, a style he refers to as “barefoot luxury.” It’s another type of L.A. aesthetic, catering to the kind of buyer who is rich, obviously, but more concerned with livability than flashiness, and it’s an approach that’s won him acclaim.

“He thinks out of the box,” said Aaron Kirman, a luxury broker at Compass, characterizing Tavangarian’s projects as the kind of modern, playful houses billionaires actually want to live in. Umansky, who represented the buyer of Tavangarian’s Bel Air mansion, even threw out a comparison to Michelangelo: Tavangarian allows his house to emerge from the landscape, he said, much as the sculptor once described his works as emerging from marble.

But Tavangarian is also playing to another audience. Inside Arya’s immaculately designed office, an assistant pulled up YouTube videos of Tavangarian’s two most famous recent spec projects. As the sleek videos showcased such amenities as a transparent car elevator and walk-in wine cellar, Tavangarian occasionally interjected, directing his employee to pause the tape so he could explain the thinking that goes into subtle features like electric-frosting poolside glass (for privacy) or a porcelain concrete wall that perfectly mimics the vertical grain of Canadian cedar (“everything is symbolic”).

It was the kind of obsessively detailed planning that comes from decades of accumulated understanding of the desires of some of the world’s richest people. But Tavangarian was also surprisingly concerned with the reaction of the masses.

“Most likely 99.999 percent of them could never afford that, right?” he said. “They’re almost like looking through the glass.” Yet the videos’ tens of millions of views were proof that his creations were connecting with people, and “that’s been probably one of the most rewarding sides of this thing.”

Then the luxury developer asked to go back to the previous video. He wanted to see the comments.