The failure last year to produce a housing plan acceptable to state authorities has set up the City of Santa Monica for an unprecedented development frenzy.

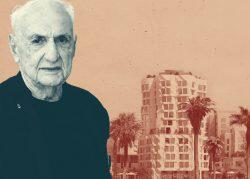

WS Communities, a firm founded by prominent apartment developer and landlord Neil Shekhter, rushed to capitalize on the city’s failures, submitting applications to build housing projects that would normally require years of review and planning to see approval.

At least 12 projects totaling almost 4,000 units were submitted to the city under so-called builder’s remedy applications as of Tuesday, and at least two more have been submitted since then, according to a source familiar with the matter.

Those projects alone would represent an addition of more than 7 percent to the city’s housing stock. Most of the projects filed preliminary applications with the city, meaning these projects will get the green light even though they’re in the early stages of development.

“This is not theoretical,” Jing Yeo, a city planning manager, said at a City Council meeting on Tuesday about the builder’s remedy projects. “This is very real and it’s happening.”

“We felt this was the best way to try and get housing built as fast as possible,” said Scott Walter, CEO of WS Communities, the firm that filed 10 project applications with the city. “And that’s basically why we went this route.”

WS Communities filed its applications, which total around a few thousand units, within the last few weeks, Walter said, in part because it foresaw an otherwise lengthy approvals timeline if it waited for Santa Monica to update its zoning code.

“It’s just a long time to just wait,” he said, “to begin a future entitlement process.”

Builder’s remedy

Santa Monica’s pending construction boom is the consequence of a decades-old state law known as the Housing Accountability Act. The 1990 law — which amounted to a kind of precursor to California’s more recent flurry of pro-density state legislation — was an effort to incentivize construction by imposing a penalty if cities fail to pass general plans that comply with state housing goals.

Under the law, cities that are deemed noncompliant lose the ability to approve or deny projects with affordable housing components, and those projects instead are automatically approved. Projects qualify if at least 20 percent of their units are affordable, or if the entire project is dedicated to moderate income tenants.

Although Santa Monica passed its Housing Element last fall, the state later rejected it, sending the city into noncompliance. On Tuesday, the Santa Monica City Council approved a new housing plan, but the city’s months of noncompliance left the gap for developers to receive the by-right “builder’s remedy” approval. The state must still approve the plan, meaning any developer could still come in and submit a builder’s remedy project.

When councilmember Phil Brock asked if that was true at the Tuesday meeting, he was shushed and hushed by other members, who didn’t want Brock advertising that opportunity.

While the state’s “builder’s remedy” law has been in place for decades, for much of that time it was considered weak and rarely invoked by developers, in part because of ambiguities around the way it was written. More recently California has passed additional laws, including SB 35, which was enacted in 2017 and strengthened the state’s hand by requiring cities to include rental information in their housing plans, among other provisions.

The flurry of builder’s remedy applications revealed at the City Council meeting on Tuesday has the potential to remake Santa Monica, a wealthy coastal city that for decades was characterized mostly by low-density building. It also presented developers with a rare opportunity of a streamlined approval process stemming from the city’s bureaucratic lapse.

At Tuesday’s meeting, council members — unaccustomed to being sidelined from the local approvals process — expressed a sense of bewilderment and confusion.

“This is a state hammer,” council member Brock said at the meeting. Yeo, the city manager, agreed: “Correct.”

A representative for the city did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Read more