The beachfront lot in Jupiter, Florida, was set to close for $4.9 million when Milla Russo went looking for a commission.

With her husband, Andrew Russo, she leads a top team in Palm Beach County, their licenses held by a brokerage called Illustrated Properties.

In the Jupiter deal, Illustrated and Compass had a listing agreement with the seller of a waterfront home lot at 12 Ocean Drive that gave each brokerage 1 percent commission on the sale price, so long as there were no cooperating brokers.

Just before the closing in the fall of 2020 a commission battle began.

Milla claimed she and Lori Schacter, another Illustrated agent, represented the buyer and were thus entitled to a $122,500 commission, according to a lawsuit later filed by the closing agent.

There was just one problem: The buyer never worked with, or was represented by, Milla or Schacter, he later testified. Two versions of the contract show the before and after. Andrew Russo’s name is on the first, replaced by those of his wife and Schacter in the second.

A Florida court ruled against the Russos in 2022, though Milla told The Real Deal that she and her husband were “wrongfully accused” and that the modification was meant to reflect an increased commission that Andrew had negotiated but not secured in writing.

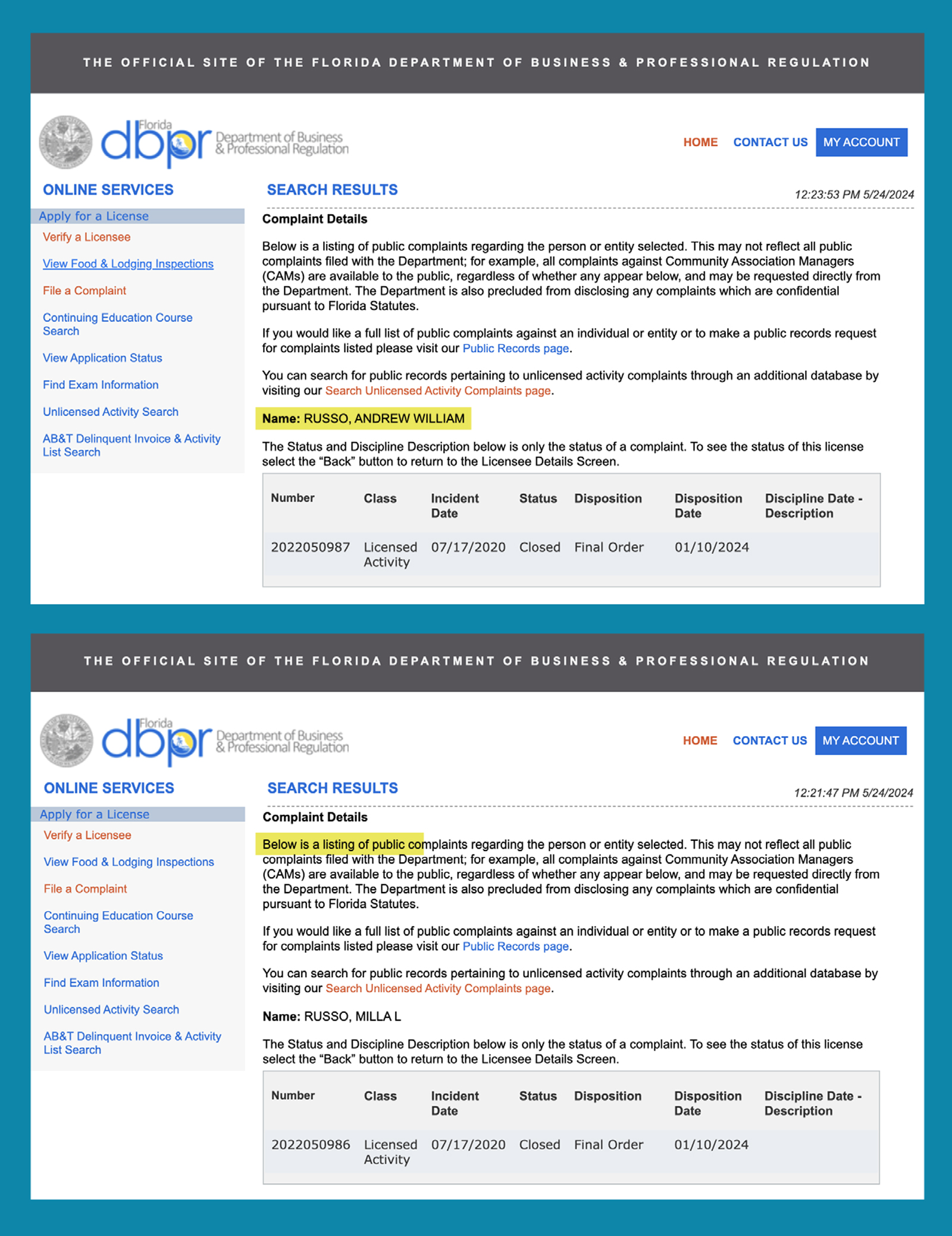

Yet two years later, if curious clients or potential partners were to look on Florida’s licensure database to see if any complaints had been filed against the power couple, they would not easily discover the alleged misdeeds.

Both have active licenses, and just one line appears for each noting a complaint over “licensed activity” with a final order entered in January. On their website, the Russos still claim to produce “very happy and satisfied, and often repeat clients” and have a roster of multimillion-dollar listings in Vero Beach, North Palm Beach and Jupiter.

That there was little repercussion and barely a blemish on the Russos’ records is just one sign of the lack of enforcement in the brokerage industry, which sees thousands of agents continue to work even after legally sufficient complaints about their conduct are filed. In an industry that purports to run on trust between client and broker or among brokers on different sides of the table, the weak regulation acts like a black box that allows only insiders to know about and avoid bad actors.

“As a licensed real estate agent who does the right thing, it is so disappointing that apparently these rules don’t matter. They broke the law, they changed a contract, lied about it, passed it off.”

Buyers and sellers, some making the most important financial decisions of their lives, lack crucial information, but agents outside the whisper network are also left vulnerable.

The industry has remained under-regulated even as home prices have soared, turning what used to be four walls and a roof into a financial instrument. Yet in contrast to the brokers who help buy and sell other investment vehicles for ordinary people, there is barely any oversight of those who steer residential transactions.

That means brokers like “the Jills” — a top Coldwell Banker team — can get away with having allegedly tweaked property information on the MLS to manipulate a key metric of the market’s health and still be one of the most in-demand duos. Or that Compass can roll out the red carpet for Josh Flagg, a Los Angeles agent who allegedly left Douglas Elliman after concerns arose over whether he had presented all offers to the seller, as required by law, in a case where he represented both seller and buyer. An attorney for Flagg denied that the agent was ever terminated or engaged in “any wrongful or improper conduct in relation to the sale.”

Brokers put checkered pasts behind them all across the U.S., but the huge influx of wealth that descended on Florida in recent years, and the real estate agents who followed, turned the state into a Wild West for real estate lawlessness, agents and attorneys say. In addition, the multibillion-dollar industry makes the state’s economy hum: Nearly $200 billion in residential sales closed last year, according to the Florida Realtors. Higher property values mean homes sell for more and fetch higher commissions, reducing desire for accountability but raising the stakes of having none.

“There’s no state income tax [in Florida]. As a result of that, the state, the city, the county, the school board, the only way they’re able to fill their coffers, primarily, is real estate,” broker and market consultant Peter Zalewski said. “The people out west make money selling tile to condos out east. People going on cruises are being pitched condos. It’s always been about real estate, if you go back to the boom of the 1920s.”

In the Russo case, Milla’s commission claim prompted the closing agent to file a lawsuit. That’s when the buyer, Ron Fink, made clear that he hadn’t worked with Milla or Schacter. Schacter, who declined to comment to The Real Deal, confirmed in a deposition that she was not involved in the deal — and that she was upset about it.

In text messages sent to Russo, Schacter referred to the “deceitful manner” in which the situation was handled.

“You should be glad I don’t call the seller who knows me to tell him the story, especially not knowing, you put my name on it and it was you and Andrew who sold the property,” Schacter wrote to Russo, as revealed in Schacter’s deposition.

The Russos were ordered to pay the closing agency’s attorney fees and interest after the judge ruled against them. Judge Richard Oftedal wrote that the litigation was based on “deceptive claims” and fraud perpetrated by the Russos and Illustrated Properties.

Milla Russo said the accusations came from an agent who “wanted to take us down, and she almost succeeded.”

Her husband’s failure to get his work with the buyer down on paper had an explanation too: “He was just being dumb and reckless,” Milla told TRD.

“I understand about the law and all of that, and we were dumb,” she said. “If we were more careful, this wouldn’t have happened.”

Andrew Russo declined to comment by press time. Illustrated Properties, part of the Pappas family’s Keyes Company, declined to comment.

Weak regulation

As the suit played out in court, complaints against Andrew and Milla Russo also made their way to the state agency that deals with real estate problems. Florida’s Department of Business and Professional Regulation, which oversees licensing and regulation of both residential and commercial real estate agents, investigated the complaints.

The Florida Real Estate Commission, the division in charge of adjudicating them, dismissed the complaints against the Russos with prejudice. This means they can’t be brought again.

DBPR is the only government authority that can revoke a broker or real estate agent’s license, or issue fines or suspensions. State law outlines punishments ranging from fines — the maximum is $5,000 per count — to felony charges, but few agents face serious repercussions. Things are busy at DBPR. As a state licensing bureau, it is responsible for the licensing and regulation of more than half a million professionals, from architects and contractors to geologists and veterinarians. The process for punishing a wayward broker only even starts if another broker, agent or consumer reports violations of state law.

“As a licensed real estate agent who does the right thing, it is so disappointing that apparently these rules don’t matter,” said Holly Meyer Lucas, an agent with Compass who represented the seller in the Jupiter deal and filed a complaint against the Russos. “They broke the law, they changed a contract, lied about it, passed it off. The fact that the state won’t hold their licenses accountable … is deeply disappointing and demoralizing.”

The seven members of the board that comprises FREC are appointed by the governor. According to the state, four of those commissioners must be licensed real estate brokers in the state with an active license for at least five years before joining, and two of them must have never been brokers or sales associates. One member must be at least 60 years old.

FREC Executive Director Giuvanna Corona, a real estate agent, signed the final orders dismissing the Russo complaints. Corona did not respond to requests for comment.

Brokerages are known to defend their agents if they are top producers. On top of harming consumers, the laxity disincentives agents and brokers who follow the rules.

“There’s such crystal-clear rules around what a licensee can or can’t do, but it’s at the discretion of the higher-ups,” Meyer Lucas said, including the leadership at Illustrated Properties.

Contrast this with lawyers, who face public reprimands or disbarment for stepping out of line. Securities brokers face serious repercussions for low-level rule-breaking that catches the attention of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, known as FINRA.

The swamp

The real estate hustle in Florida dates back to the late 1800s. The phrase “Ponzi scheme” comes from Charles Ponzi, an Italian immigrant who fled Massachusetts to avoid a second prison sentence there and ended up in Jacksonville in the 1920s, where he set up a business to sell “prime” property in Florida that was really just swampland.

Florida drained the swamps and became a tourism and real estate empire. Regulation is better, too, and complaints do get filed. More than 18,400 real estate complaints were submitted to DBPR between 2020 and 2023 for both residential and commercial issues.

Only 9,752 were found to be legally sufficient — meaning that the alleged problems would violate state law. From this group, just 47 agents had their licenses suspended and 407 relinquished their licenses or had them revoked. Some of the investigations are ongoing or have not yet gone before FREC, according to the state. License revocations are permanent.

but offers no details on what the complaint entailed.

Beyond the state’s complaint framework, trade organizations often handle ethics violations. On the one hand, this is a natural fit — groups have their own codes of ethics and professional standards, and the industry has an interest in seeming trustworthy. But from a skeptical perspective, it may seem unlikely that organizations that lobby for less government regulation would be up to the task of regulating their own. In Florida, home to the largest state and local real estate trade organizations, the complaint process is completely confidential, so it is impossible to know how many filings there are.

Miami Realtors, the largest local association of its kind in the country, with more than 60,000 members across South Florida, received only 103 complaints in 2023 and just 30 so far this year, according to written responses provided by Evian White De Leon, its chief legal counsel.

The chapter encourages the parties involved in a potential complaint to first try to resolve their dispute through a confidential ombudsman program. If that doesn’t work, the complainant can file and eventually go before one of the organization’s ethics boards.

White De Leon declined to disclose the outcomes of those complaints, citing confidentiality.

To be sure, not every case is headline-worthy; most probably are not. Low-level offenses include not marking a sale pending or closed in the MLS in a timely manner.

But there are big ones, including arguably the highest-profile complaint filed against real estate agents in the U.S.

In 2015, former Miami real estate agent Kevin Tomlinson filed a complaint with Miami Realtors against Jill Hertzberg, Jill Eber and other members of the top-ranked Coldwell Banker team known as the Jills.

Tomlinson discovered that the Jills had manipulated dozens of listings in the MLS, changing property identifiers such as city, ZIP code and subdivision area. The massive manipulation likely affected home appraisal amounts and mortgages, comparable sales and market-wide data.

The Jills blamed it on an office associate and said they were unaware of listings being changed.

Tomlinson didn’t file a complaint with the state. Instead, he went to Miami Realtors, which, to this day, refuses to comment on the status or outcome, citing the required confidentiality in ethics proceedings.

Tomlinson then made an attempt — caught on tape — to extort the Jills for $800,000 and was convicted. After he violated his parole and ended up in jail for just under a year, his sordid saga wound up overshadowing the original transgressions, for which there were almost no consequences.

In 2016, a year after Tomlinson blew the whistle, Miami Realtors instituted $5,000 fines for MLS manipulations, but the Jills were not publicly reprimanded. In 2019, they merged with Judy Zeder’s group to form a mega-team at Coldwell Banker.

It’s unclear if either Jill faced any direct penalties, and they did not respond to requests for comment.

“What message does that send? One of the problems with non-enforcement is, you read about that and a Realtor thinks ‘OK, I can manipulate the MLS,’” Miami attorney David Winker said.

Tomlinson, who declined to comment on the Jills saga, believes that brokerages have “turned a blind eye toward agents and brokers [who misbehave] because they’re bringing in money.”

And, because many homebuyers and sellers only purchase and sell their homes once or twice in their lifetimes, they might write off a bad experience with a broker as a one-off horror story, not evidence of a systemic problem.

In addition, complaining is not worth the hassle for most consumers. “The time and effort it takes to go through many of these things is generally not worth other Realtors’ or the public’s effort,” real estate attorney Claudia Cobreiro said.

Cobreiro, who has represented clients in front of a Miami Realtors ethics board, said most of her clients who have issues with an agent prefer to just avoid that person in the future. “A lot of people complain about it,” she said, referring to alleged ethical violations, but they don’t end up taking any action.

Instead, offending agents end up on an unofficial “blacklist.” If you know to avoid them, you do.

House-warning

Free of consequence, the broker horror stories mount. The Realtors’ ethics boards are dealing with them “every single day,” Cobreiro said. In a particularly bad case, a Florida agent went so far as to put multiple buyers in contract for the same property. A buyer finally filed a complaint with the Miami Realtors ethics board, Cobreiro said. The case never made it to the courts.

The punishment was a “slap on the wrist,” said Cobreiro, who could not share further specifics about how far each buyer got with their contract or if earnest money was exchanged.

“Ultimately, I don’t think the MLS is looking to take away anyone’s license,” she said.

Other industries, like financial services, have tougher oversight. Congress specifically asks FINRA to “protect America’s investors by making sure the broker-dealer industry operates fairly and honestly,” according to the corporation’s site — even on small transactions. Its database, BrokerCheck, allows consumers to see if any disclosures exist; they can easily click on those to read more about the allegations and see the status and initiation date of a case, a stark contrast to what DBPR offers.

FINRA is known to carry a lot of clout, said attorney Robert Herskovits, who represents banks, other financial firms and individuals in the industry.

FINRA publishes a monthly report that summarizes all of its disciplinary actions or settlements.

DBPR does release names of real estate agents and brokers who are disciplined, but it does not share details about the cases in those public notices.

“If there was a repeat offender in the securities industry, they would be [under] scrutiny by regulators and they wouldn’t get hired by top-tier firms,” Herskovits said.

“The self-policing industry keeps things that should be brought to light in the dark. That needs to be modernized. ”

In 2020, Winker, a proponent of increased transparency, represented the buyer of a house in the Miami neighborhood of Shenandoah.

The buyer, Jessica La Torre, expected that the garage at her new $370,000, two-bedroom, one-bathroom home had been legally converted to a one-bedroom, one-bathroom apartment. That was what the listing said. (The description remains on the websites today.)

La Torre discovered that the garage was not legally converted after she began making cosmetic repairs. She had to pay for the work herself.

In a lawsuit against the listing agent, the agent’s brokerage, the sellers and the appraisal firm, La Torre alleged that the defendants engaged in fraud, negligent misrepresentation, breach of contract and civil conspiracy.

The lawsuit was eventually dismissed after the two parties reached a settlement, court records show. Potential clients of the agent or brokerage would be unlikely to discover it.

In terms of price points, La Torre is separated from Ron Fink by a factor of 14. But in both cases, either the buyer or others involved in the deal were the ones tasked with bringing bad actors to account, instead of a regulatory agency meant to keep consumers safe.

As for the Russos, they are licensed with Illustrated Properties, and Milla Russo’s name still appears as the buyer’s representative in the deal on the MLS.

Coldwell Banker stuck with the Jills, who grew stronger with their merger with the Zeder team. The combined team now dominates annual rankings.

Josh Flagg got set up at Compass with $400 million in listings and a glowing quote from CEO Robert Reffkin in a press release announcing his arrival.

Tomlinson faced the only real punishment. After being charged with extortion, he lost his job. At his sentencing, the judge banned him from working in the real estate industry.

“The self-policing industry,” Tomlinson said, “keeps things that should be brought to light in the dark. That needs to be modernized.”