Bobby Turner, a native Angeleno, founded social impact investment firm Turner Impact Capital two years ago. His goal: to acquire $1 billion of workforce rental housing for residents earning no more than 80 percent of an area’s median income. So far, he’s backed projects in Miami and Dallas — but he has steered clear of investments in his hometown.

“If the community itself is not willing to eliminate political risk, why would I ever invest there?” Turner asked.

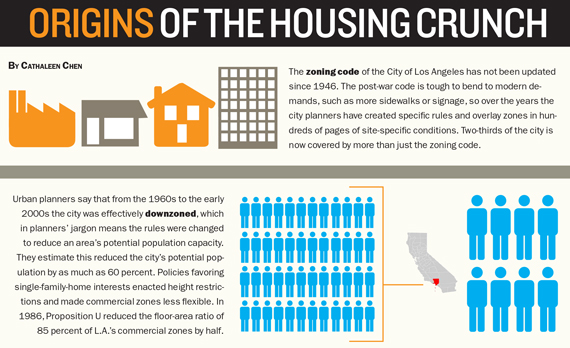

Building affordable housing in Los Angeles — a sprawling 503-square-mile metropolis of mostly suburban neighborhoods — has been difficult and expensive for decades. A complex web of archaic zoning, outmoded community plans and a spirited group of “not in my backyard” protesters has discouraged many developers, like Turner, from even trying.

And now, political risk is really rearing its scary head. Voters will go to the polls on March 7 to decide whether to temporarily halt most large development projects in L.A. Opponents of the measure say this is already having a chilling effect on the market.

The Neighborhood Integrity Initiative, also known as Measure S, would put a two-year moratorium on all projects requiring amendments to the city’s general plan, which given L.A.’s byzantine zoning regulations could be most major projects in the city. The initiative, which aims to pause the development process until the City of Los Angeles’ general plan can be overhauled, would make exceptions only for residential developments entirely made up of affordable housing that would not amend the general plan — circumstances that are very rare.

If passed, the measure could pose problems for Mayor Eric Garcetti, who laid out an ambitious goal of building 100,000 new housing units by 2021, while doubling the production of affordable housing for low-income Angelenos, when he took office in 2013. His stated goal is to increase residential density around transit hubs. “Our Metro rail system is in the midst of an historic expansion, and we should be leveraging that growth to ensure we are bringing housing to key corridors,” he recently told The Real Deal.

Although the mayor hasn’t publicly opposed the ballot measure, local developers and business leaders say it would effectively scuttle his plans to expand affordable housing. Gary Toebben, president and CEO of the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce, told a recent industry meeting that there is “no way in the world” the mayor could reach his goal of 100,000 new housing units if the voters approve the ballot measure.

For their part, backers of the anti-development measure say hitting the pause button would give the City Council time to focus on updating land-use policies before allowing new construction that would ultimately increase neighborhood density. The Coalition to Preserve L.A., the well-funded backers of the campaign for the ballot measure, did not return TRD’s requests for comment.

Maxed out

By some accounts, the city has hung out the “no vacancy” sign. The population recently surpassed 4 million for the first time, and urban planners estimate that the current zoning gives it a potential population capacity of 4.3 million.

Development has traditionally favored single-family homes, leaving some areas with a dearth of multifamily housing.

With so few apartments available, it’s no wonder that L.A. is among the nation’s most expensive cities for renters. Median rent for a two-bedroom apartment is $2,600 a month, making it the sixth-priciest city in the country, according to data from Apartment List, a website that aggregates apartment listings. Renters pay far more in affluent neighborhoods like Venice, where the median is $5,000, and Westwood, where it is $4,280.

The high cost of apartments means that one-third of the city’s renters spend nearly half of their income on rent, according to an NYU Furman Center March 2016 study.

Homeownership is another challenge. A buyer would need to make $91,302 to comfortably afford the median-priced home in the city, which rose by about 7 percent to $530,000 between November 2015 and November 2016, according to data from Corelogic and Redfin.

Yet those in the industry say local policymakers have made decisions over several decades that have worsened the housing shortage.

According to a much-quoted 2013 dissertation by then UCLA Ph.D. student Gregory Morrow, the city was zoned for a population capacity of 10 million in 1960, when it had 2.5 million residents. But, Morrow argued, the capacity has been reduced to 4.3 million through anti-growth legislation and frequent “downzoning,” resulting in reducing the potential density of an area.

Extra credit

California’s chief strategy for adding to the affordable housing stock is to offer incentives to developers through the state’s density-bonus law. Enacted in 1979, the law gives incentives to developers to include price-restricted low-income housing in development projects. Those units are typically reserved for residents earning 80 percent or less of the area median income, and sometimes awarded through a housing lottery.

Depending on what percentage of units the developer earmarks as affordable, a project can receive a by-right density bonus of up to 35 percent, adding more units to properties and allowing the developer to make a similar return on the project as they would have if it had been entirely priced at the going market rate.

Depending on what percentage of units the developer earmarks as affordable, a project can receive a by-right density bonus of up to 35 percent, adding more units to properties and allowing the developer to make a similar return on the project as they would have if it had been entirely priced at the going market rate.

While the density bonus may look good on paper, the developer still has to sell more market-rate units to achieve the profit they would have had selling fewer units in a project without an affordable housing component. Other concessions for adding affordable housing may include easing rules on parking or the setback distance, but those often aren’t enough of a sweetener to spur affordable housing development, said Allan Abshez, a land-use attorney at Loeb & Loeb.

Even if a project has been granted a density bonus and other concessions, the entitlement process can still be lengthy — and subject to opposition by local anti-development activists. “From the perspective of wanting to generate as much density-bonus housing as possible, that’s a defect in the system,” Abshez said.

Community opposition to new development — often referred to as NIMBYism — has hampered construction in certain parts of the city, according to Paavo Monkkonen, an associate professor of urban planning at UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs.

Monkkonen has studied L.A.’s neighborhood council system. He said the public input and legal processes used to block developments favor wealthy homeowners with the resources to organize opposition to specific neighborhood projects. Their tactics could include forcing the city to include requirements that go beyond baseline-zoning standards, or suing a project under the development statutes outlined in the California Environmental Quality Act.

“A lot of the places near amenities and near jobs have strong political powers at the neighborhood level, so they’re able to prevent new development,” Monkkonen said.

Ralph McLaughlin, the chief economist at Trulia, told a recent L.A. business conference that some large cities were making strides in addressing the roadblocks to building affordable housing. He cited Houston, which he said has less convoluted zoning than L.A., and Seattle, where the city is offering tax incentives for new affordable housing. “If we have shortage of, say, milk, and milk becomes expensive, we don’t make the providers of milk provide affordable milk,” McLaughlin said. “We subsidize the production.”