Every week, a different co-working company tries to sell itself to Jeff Reinstein. The chief executive of Premier Business Centers — who’s been in the game since 2002, when the preferred term used to describe such flexible office space was “executive office suites” — says its just part of the boom-and-bust cycle of the business.

“There’s a lot of people looking to get in, and there’s a lot of people looking to get out,” said Reinstein.

The amount of co-working space in Los Angeles County has grown 500 percent since 2008, according to a report released by JLL in September.

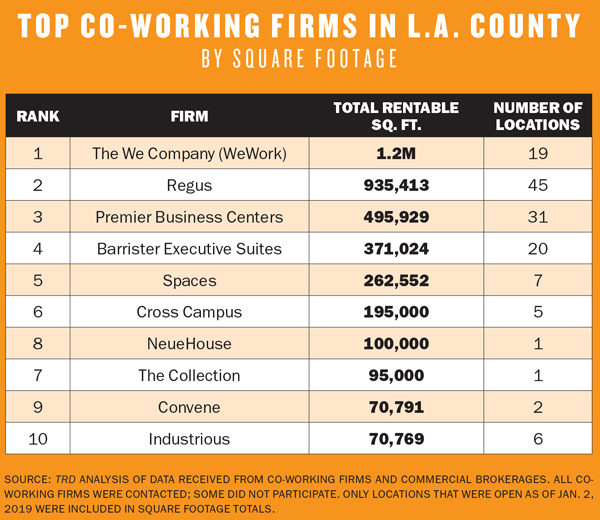

Premier — L.A.’s third-largest shared office space manager, according to The Real Deal’s ranking of the top co-working firms operating in the county — staked its claim in the area early, beating out major players WeWork and Regus by taking advantage of low rents in the wake of the recession.

Reinstein and other observers see another such shakeup happening as the amount of co-working space continues to grow, putting L.A. in second place nationally, just behind Manhattan, with 3.54 million square feet of flexible office space, according to a report from CBRE. Smaller operators continue to crop up while the giants continue to expand, sometimes with two locations within blocks of each other.

“I think I see more companies failing [in the future],” said Reinstein. “Rents are very high, and there’s a lot more competition.”

Asking rents for office space in greater L.A. were $3.34 per square foot per month at the end of 2018, according to Eric Kenas, director of research at Cushman & Wakefield.

Co-working space only makes up about 2 percent of the overall office space market in greater L.A., said Kenas. But observers expect the amount of co-working space to keep growing.

No. 1 in TRD’s ranking of co-working operators is national behemoth WeWork — rechristened the We Company at the start of 2019 — which controls 1.2 million square feet in L.A. County. To rank the co-working firms by square footage, TRD gathered data from commercial brokerages JLL, Cushman & Wakefield and NKF. Only locations that were open as of Jan. 2, 2019 were included. TRD shared the data with the co-working firms, but not all of them participated.

No. 1 in TRD’s ranking of co-working operators is national behemoth WeWork — rechristened the We Company at the start of 2019 — which controls 1.2 million square feet in L.A. County. To rank the co-working firms by square footage, TRD gathered data from commercial brokerages JLL, Cushman & Wakefield and NKF. Only locations that were open as of Jan. 2, 2019 were included. TRD shared the data with the co-working firms, but not all of them participated.

Profit margins on these spaces vary widely based on the specifics of a deal, according to Jerome Chang, founder of BlankSpaces, one of the oldest of the current crop of co-working companies in the area. His company, founded in 2008, charges around $200 per month for an individual to use a shared workspace at the company’s approximately 10,000-square-foot Santa Monica location, or around $1,000 per month for a private one-person office at the same location.

Meanwhile, L.A.’s spread-out geography and traffic woes are prompting companies like IWG (the Swiss firm that owns the Spaces and Regus brands) to hunt for space within neighboring submarkets like Brentwood and Santa Monica, according to Michael Berretta, vice president of network development in the Americas for IWG.

“One thing that’s very unique about Southern California is the density overlaid with how much traffic there is,” said Berretta, noting that it can take almost half an hour to drive a few miles. “It makes it very difficult to travel. Because of that, having a network of spaces becomes important.”

The company’s Regus brand, which is more akin to a traditional business center, and Spaces, which has a more bohemian vibe, have the second- and fifth-largest amount of rentable square footage in the county, respectively.

Another source of growth locally is the industry-wide shift away from tenants like freelancers and small startups in favor of large corporations, which some co-working companies see as more profitable. Many shared office space operators are also moving toward a model of profit-sharing with landlords instead of leases. Such arrangements allow co-working companies to offload some of the risk while giving landlords more of the upside, sources said.

Fragmented market

The increased popularity of co-working over the last several years has fueled the growth of the more savvy operators. Irvine-based Premier Business Centers, which has the bulk of its portfolio on the West Coast, has doubled in size since the recession, when it acquired competitors who went under. The company recognized the early signs of the downturn and slowed its growth in 2006 while other competitors plowed full steam ahead, according to chief executive Reinstein.

“You could pick up a center for little to no money,” he said. “Landlords had a lot of space they wanted to rent out.”

The individual office space that Premier rents to its clients ranges from 80 to 250 square feet, compared to the 50 square feet he said some of his competitors rent out as a one-person office. And Premier’s amenities are distinctly old-school, offering just coffee and tea over the Ping-Pong tables and beer that are de rigueur at newer co-working firms. Its tenants have included Microsoft, Expedia and Wells Fargo, and its 32 Los Angeles locations tend to be in wealthier areas such as Beverly Hills, where executives live, said Reinstein.

Ronen Olshansky, chief executive and co-founder of Cross Campus, the sixth-largest operator locally, expects to see the number of co-working companies decrease. Although his company has only about a third of Premier’s market share, with almost 195,000 square feet of rentable space at its five L.A. County locations, Olshansky also gets approached weekly by the owners of co-working firms looking to exit the business. His firm, which is headquartered in Santa Monica, recently acquired a small co-working company by the name of DeskHub, giving it a location in San Diego and one in Scottsdale, Arizona.

“I think the industry will go through a massive period of consolidation over the next year,” said Olshansky. “It’s too fragmented an industry. Ninety-nine percent of co-working companies are too small or unsustainable.”

The companies approaching Cross Campus haven’t built up an operating platform that allows them to run multiple locations, Olshanksy said. His company has invested not just in its physical space but also in things like its technology, intellectual property and hiring and training infrastructure, which enhance the customer experience, he said.

Meanwhile, larger co-working companies are able to leverage an economy of scale on things ranging from contracts with FedEx to internet providers, according to Reinstein. Such companies also tend to have larger marketing budgets. Premier, which has 275 employees, has a five-person marketing division.

Meanwhile, larger co-working companies are able to leverage an economy of scale on things ranging from contracts with FedEx to internet providers, according to Reinstein. Such companies also tend to have larger marketing budgets. Premier, which has 275 employees, has a five-person marketing division.

The space network

Companies with larger portfolios have an edge, said IWG’s Berretta. The company’s almost 3,300 locations under the Regus and Spaces brands, in more than 110 countries, allow organizations to quickly set up operations all over the world, he said.

“Companies want the ability to grow and shrink when needed and to transfer obligations across different cities,” said Berretta. “That kind of global network is unheard of in traditional real estate.”

IWG is applying a similar strategy of building a “network within a network” across L.A.’s various neighborhoods.

Peter Belisle, market director of the Southwest region at JLL, thinks more companies operating locally will opt to have four or five smaller locations in order to court potential employees who might be turned off by a long drive to a large central headquarters. It’s what he calls a “hub and spoke” strategy. While perhaps inconvenient in some ways to have a spread-out workforce, Belisle notes that employees within the same office often also communicate through technology rather than face to face.

“We’re really talking about a demographic shift in worker behavior,” said Belisle. “That’s behind a lot of this. It’s a market force nobody can control.”

Having multiple offices is part of a broader strategy that some businesses are trying to employ in order to compete with tech companies known for their amenities, Belisle said.

Take for example law firm Kjar, McKenna & Stockalper, which occupies about 70 desks at Cross Campus’ El Segundo location. Olshansky said that while some real estate professionals have been surprised that such a business would be willing to forsake privacy by being in a co-working space, he thinks it points the way toward the future.

“They’re a litigation law firm, but they want to attract younger talent, millennials, and they recognize that the work environment is part of it,” he said. “They looked at the flexibility, the great design, our in-house events platform, the cost [efficiency], and they made the decision that it was worth the trade-off [of privacy].”

Enterprise clients

Over the past year, Cross Campus has been approached by larger tenants looking to have it build out and manage their spaces. The company designed such a location in El Segundo for real estate investment startup PeerStreet, which has raised $50.6 million and has between 100 to 250 employees, according to Crunchbase. Such enterprise deals now make up a quarter of Cross Campus’ revenue, Olshansky said.

Other players including the We Company, are making similar arrangements a much larger part of their business. CBRE announced in October that it was creating a new division, Hana, to partner with institutional property owners to provide flexible office space for large corporate users.

A change this year in the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles is also driving larger corporations to seek out co-working solutions instead of more traditional long-term leases. Starting on Jan. 1, public companies must report any operating leases as liabilities on their balance sheets, so a 10-year lease costing $1 million annually will be reported as a $10 million liability. Prior to the change, more than 85 percent of lease commitments held by publicly traded companies weren’t listed on balance sheets, according to an October report from JLL. Such a change affects metrics considered by investors, such as debt-to-equity ratio.

Pairing up with landlords

Another industry-wide change playing out locally is the shift away from co-working companies signing traditional leases with landlords. Increasingly, these firms are negotiating management or joint-venture agreements with the landlord. One of the largest co-working campuses coming online in 2019 is in the Playa District. New York-based co-working company Industrious and office landlord EQ Office (formerly known as Equity Office Properties) have an agreement to manage the Howard Hughes Center there, which contains more than 100,000 square feet.

Brookfield Property Partners recently teamed up with co-working company Convene to open 50,000 square feet of work and meeting space at the Wells Fargo Center at 333 South Grand Avenue and 20,000 square feet at 777 South Figueroa Street. The project was Convene’s first foray into the West Coast market.

IWG, which manages over a million feet of rentable space locally between its Regus and Spaces brands, plans to grow its L.A. footprint over the next year and a half primarily through management agreements, according to Berretta.

“Owners and landlords are realizing that in order to remain competitive, they have to offer a highly amenitized building — roof patios, outdoor space, full-service gyms, enhanced food and beverage — or integrate co-working to activate areas of the building that are not as interesting,” said Berretta.

Berretta compared the co-working management setup to that of the hotel industry, where a property owner might work with a hotel operator to select a brand appropriate for the location and manage the hotel.

Chang, of BlankSpaces, said that such deals remove some of the risk for companies such as his, which counts Compass among its tenants. “I can grow on someone else’s dime,” he said. “I can do what I do best: Operate.”

BlankSpaces, which currently has between 30,000 and 35,000 square feet at its three locations in L.A., will expand to a total of just under 50,000 square feet when it opens locations in Larchmont, Irvine and Long Beach this year under management agreements, Chang said.

Room for boutiques

Some operators believe that there is still money to be made from smaller companies and solo entrepreneurs, especially if a downturn is on the horizon. Despite taking on more enterprise clients, Cross Campus plans to continue servicing the smaller types of businesses that helped it grow.

“You sort of lose the environment if you go completely toward an enterprise model,” said Olshansky. “Large companies love having small businesses in the

same community. Small companies feel validated by larger companies in the community.”

Cross Campus charges around $300 per month for 24/7 access to one of its shared workspaces; its one-person offices start at $600 per month.

With each location having between 8,000 and 10,000 square feet, BlankSpaces isn’t able to devote large amounts of space to enterprise clients, Chang said. But having smaller spaces allows the operator more choices in neighborhoods untouched by bigger players, such as Larchmont and Calabasas, which Chang is eyeing.

“Boutique co-working is definitely viable,” he said. “Hilton is huge, but the Ace Hotel does fine.”