UPDATED Dec. 21, 1 p.m. For the past 42 years, members of the Miami Design Preservation League have fought to protect buildings constructed on Miami Beach during the first half of the 20th century from the wrecking ball.

Ironically, this same group, which was founded to help protect history, nearly became history when the Miami Design Preservation League (MDPL) went to war with itself this year — a conflict that included allegations of “vote buying” levied against a man who likes to call himself the Prince of Darkness.

And, while this particular conflict has (mostly) ended, more trouble is brewing as some members of the real estate sector are questioning the decisions of the board. MDPL did, after all, help craft many of the regulations that make it challenging to develop real estate in parts of Miami Beach today.

“Miami Beach has been anti-development for too long, and now it’s suffering the economic consequences because of it,” said Neisen Kasdin, a former Miami Beach mayor once affiliated with MDPL who is now a land use attorney whose clients include developers in Miami and Miami Beach.

MDPL nearly fell apart this summer after two factions went to court over who should lead the organization. The main source of the friction was Daniel Ciraldo. A tall, lanky former business consultant, Ciraldo joined MDPL as a volunteer back in 2012. By January of 2014, Ciraldo was hired as a historic preservation officer. In March 2017, he was made executive director.

Supporters insist that Ciraldo is exactly what MDPL needs to become a stronger organization. “He came in and he organized [MDPL] to a very, professional level,” insisted Nancy Liebman, a former Miami Beach commissioner and ex-MDPL executive director who now sits on its board of directors.

But Ciraldo’s critics dislike what they describe as his aggressive management style. They are also angry that a previous board, over the objections of then-chairman Steve Pynes, agreed to increase Ciraldo’s annual salary from $67,000 to $114,000. (MDPL has a $1.5 million annual budget, much of it coming from donations and grants from the City of Miami Beach.) They also disapproved of Ciraldo’s endorsement last year of the upzoning of Town Center in North Beach — long desired by area developers — without consulting MDPL’s full board of directors.

But Ciraldo’s critics dislike what they describe as his aggressive management style. They are also angry that a previous board, over the objections of then-chairman Steve Pynes, agreed to increase Ciraldo’s annual salary from $67,000 to $114,000. (MDPL has a $1.5 million annual budget, much of it coming from donations and grants from the City of Miami Beach.) They also disapproved of Ciraldo’s endorsement last year of the upzoning of Town Center in North Beach — long desired by area developers — without consulting MDPL’s full board of directors.

“He’s a good advocate, but I believe he does not do the job for the organization the way it should be done,” said Matti Bower, an MDPL trustee and former mayor of Miami Beach. “I think he believes that he should make all the decisions without talking to the board.”

Bower, a member of MDPL since the 1970s, said she was so worried about MDPL’s direction that she asked Randall Hilliard to join the board. Hilliard, the aforementioned “Prince of Darkness,” is a political consultant who has worked for a variety of politicians, including a few controversial ones who have been indicted for Medicare fraud (former State Senator Al Gutman), busted for bribery (former Miami Beach mayor Alex Daoud) and accused of illicit drug use (former Dade County commissioner and current fugitive Joe Gersten). Hilliard’s colorful history also involves the time he wore a wire for the FBI in a “white Speedo-style swimsuit,” as a February 2007 Key West Citizen article described it, while meeting a former Monroe County attorney at a Key West clothing-optional pool bar as part of a corruption investigation.

Bower said Hilliard has run campaigns for and against her in the past. “I knew he would get a nonprofit back to how it should be working,” she said.

But Hilliard, who insists he’s also a historic preservationist, said he was blocked by Ciraldo and his allies when he sought nomination to a board seat in March. Hilliard, Bower and other Ciraldo opponents then started recruiting new MDPL members in order to gain more control. Hilliard admitted that many of these new members joined because he asked them to.

A convoluted board election held this June brought the simmering tensions to a boil. That’s when MDPL, which previously had 125 dues-paying members, suddenly received 131 new memberships and proxy votes supporting a slate of 19 individuals, including then-chairman Steve Pynes and Hilliard, who wanted Ciraldo suspended or fired.

A convoluted board election held this June brought the simmering tensions to a boil. That’s when MDPL, which previously had 125 dues-paying members, suddenly received 131 new memberships and proxy votes supporting a slate of 19 individuals, including then-chairman Steve Pynes and Hilliard, who wanted Ciraldo suspended or fired.

The bulk of those new memberships and votes came from Hilliard, who personally brought the group to the MDPL offices at the Art Deco Welcome Center. Hilliard said he did this because the organization’s website, which normally accepts new members and counts votes during board elections, was shut down. That was also the explanation Hilliard gave for why he clipped $50 cash to each application to cover the membership fees.

Ciraldo and his supporters insisted that the proxy votes were basically paid for and wanted them declared invalid. Pynes, however, anointed the anti-Ciraldo group the winner, and suspended Ciraldo. Thereafter, the locks at MDPL’s office were changed, bank accounts for MDPL were frozen and the pro-Ciraldo slate, headed by Steve Johnson, sued the anti-Ciraldo contingent. The Pynes board filed for a temporary injunction against Ciraldo, preventing him from accessing MDPL’s website, accounts or emails and from claiming to represent MDPL.

While the two sides fought it out, the City of Miami Beach held back $100,000 in funding for the much-celebrated, 41-year-old annual Art Deco Weekend and $20,000 in grants for the group until the dispute was settled.

On Nov. 9, a settlement was reached. The Pynes slate agreed to step aside, and the board chaired by Steve Johnson and supported by Ciraldo was recognized as the true board. Ciraldo told TRD that he’s confident MDPL will get funding restored for its Art Deco Weekend, scheduled for January 18- 20.

Pynes, a partner with the Bermello Ajamil & Partners architecture firm, said his faction decided to back away from litigation for “the benefit of MDPL.” The dispute, Pynes said, was “tearing the organization apart” and it “needed to be united as one.”

Johnson agreed that had “the other side” continued to litigate, attorneys’ fees would have bankrupted the organization. “In fairness to the other side,” he said, “the reason they were ceding the control of the organization to us was, in part, for the good of the organization.”

Ciraldo said both he and the current board of MDPL just “want to get back to work” and “move on from that sad chapter.”

But not everyone has agreed to stop fighting. Last month, Hilliard filed a complaint with the Miami-Dade Commission on Ethics against three members of the anointed MDPL board who are also appointed to the influential Miami Beach Historic Preservation Board (HPB):

Jack Finglass, Kirk Paskal and Liebman. Hilliard contends that those three members could discuss projects

coming before the HPB at unadvertised MDPL meetings, a violation of Florida’s Sunshine Law. Ciraldo countered that those three members aren’t affiliated with MDPL’s advocacy subcommittee, which actually makes decisions on such matters.

Hilliard also said MDPL shouldn’t be the only undisputed voice on Miami Beach historic preservation, “particularly considering the leadership is so insular and thinks they

have the right to be an exclusive club.” As for Ciraldo, Hilliard declared: “I think Ciraldo is an overbearing narcissist.”

Ciraldo isn’t crazy about Hilliard, either. “Randy is a disgusting, habitual liar,” Ciraldo stated in an e-mail, “and he is lashing out with his usual ugly lies because his fragile ego is hurt that his attempt to buy an MDPL election in a hostile takeover failed.”

The muscle of MDPL

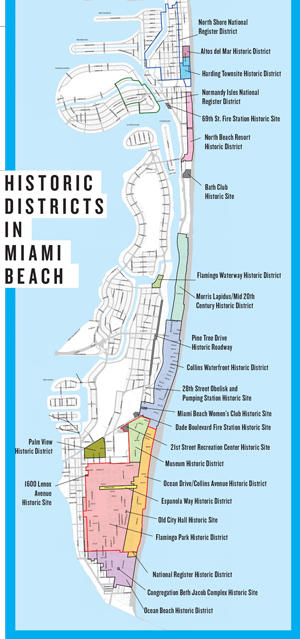

MDPL doesn’t just plan Art Deco Weekend or talk about historic preservation. Over the years, MDPL has helped forge 14 historic districts and 15 historic sites in Miami Beach. MDPL members have also helped craft regulations that now make it difficult for developers to demolish or alter buildings within these districts and sites.

At least one seat on Miami Beach’s HPB is reserved for an MDPL member. And frequently, a representative of MDPL (usually Ciraldo) will offer opinions on projects being discussed by the HPB as well as the Miami Beach City Commission.

Ana Bozovic is a Miami Beach-based broker who publishes the newsletter Analytics.Miami, which analyzes real estate trends in Miami and Miami Beach. Bozovic thinks MDPL is championing policies that are hurting Miami Beach’s economy and property values, and that its members are too blind to see it.

“Most people in the preservation camp are the opposite of objective,” said Bozovic. “They argue their stance like it is a religion.”

In 2017, real estate developer Matis Cohen, who owns properties in North Beach, negotiated with Ciraldo to get the MDPL’s support. He was granted a zoning increase for the 10-block Town Center district in exchange for persuading fellow property owners to drop their opposition to the expansion of the North Shore Historic District. That deal not only prevented organized opposition to the upzoning, but it also obtained MDPL’s seal of endorsement, which led to voters passing Town Center’s density increase in November 2017. The deal cleared the way for Cohen to build a 220-foot-tall apartment building on property he co-owns in the Town Center district.

But despite the grand bargain Cohen made with preservationists, he thinks MDPL has way too much influence in the City of Miami Beach. “The Miami Design Preservation League has lost its way,” Cohen said. “It changed from a wonderful cultural movement into a lobbyist movement to control land use and development in this city.”

Putting a price on preservation

Whether preservation efforts help or hurt a district is a source of debate. Ciraldo insists that historic districts preserve property values as well as buildings. As proof, he pointed to a 2016 report from Place Economics, a Washington, D.C.-based consulting firm, which stated that Miami-Dade single-family homes located in a historic district increased in value an average of 7.3 percent between 2002 and 2016. In contrast, houses outside of historic districts increased on average by just 3.5 percent between 2002 and 2016.

Bozovic, though, said the market wasn’t so kind to condos in the Flamingo Historic District in South Beach, according to Miami MLS data she analyzed. Back in 2007, Bozovic said the average resale price for a condo in the Flamingo District was $262,667. By the third quarter of this year, Flamingo District condos were reselling for an average price of just $218,909 each. In comparison, the South Beach condos outside that district, which includes newly constructed units, went from an average price of $670,850 in 2007 to $1.06 million in the third quarter of 2018.

But not everything about the perceived stunted growth in Miami Beach is being pinned on the MPDL. In 1997, Miami Beach voters passed a charter amendment requiring a voter referendum for any increase in floor area ratio, or FAR, along the waterfront. In 2004, the referendum requirement for FAR increases was applied to all land parcels throughout Miami Beach. FAR is a method the city uses to calculate future density.

In other words, while most city commissions can pass legislation increasing future density, in Miami Beach such things must be approved by the electorate. It’s the reason why the upzoning of the Town Center district had to first be blessed by Miami Beach voters last year.

It’s also a big reason why MDPL board member Bower became a harsh critic of Ciraldo. Bower felt it was wrong for MDPL to send out a flier urging people to vote “yes” on the Town Center referendum. Bower was against the upzoning, feeling that it would further increase traffic on an already congested barrier island.

At the very least, Bower felt that endorsing any position on Town Center’s zoning should have been decided by the full board of directors. Instead, the matter was discussed only by Ciraldo and a subcommittee. (Bower is a trustee but not a board member of MDPL.)

Ciraldo insisted that his actions have been for the good of the group and preservation as a whole. “In a leadership position, you’re open to attack,” Ciraldo said, “which is fine. It comes with the territory.”

But Bower noted that a lot of people have complained that Ciraldo can be “extremely aggressive,” especially to those who criticize him. “He cannot be a dictator,” she said. “The board is there for a reason. He’s not a god.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Ana Bozovic is affiliated with Sky Five properties.