Fifth Wall’s Brendan Wallace and Greg Smithies with The Real Deal’s Hiten Samtani (Getty, iStock)

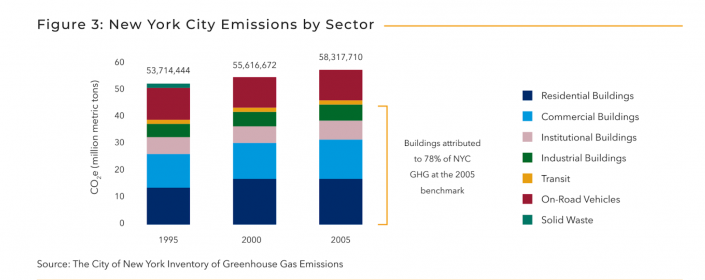

Real estate is the quiet sinner in the climate crisis. The industry might not be the Disney villain of greenhouse gases, cackling as it wreaks havoc on the world, but some estimates show it accounts for up to 40 percent of global carbon emissions. In major real estate markets such as New York, that number is over 70 percent. Why has the industry been unwilling to act on this issue? And how has it gotten away with it for so long?

Brendan Wallace is a co-founder and managing partner of Fifth Wall Ventures, the country’s largest real estate–focused venture capital firm, and Greg Smithies is a partner in its Climate Tech fund. The fund, which seeks to invest in technologies that help real estate combat climate change, this week announced its first commitment, from Canadian real estate investment giant Ivanhoe Cambridge (a subsidiary of Quebec pension manager the Caisse).

Wallace and Smithies sat down with The Real Deal for an extended conversation about the industry’s approach to climate change, what its investment in climate technologies could look like, and the potential consequences — financial, reputational and existential — of sitting on the sidelines.

“The business of doing real estate ain’t the same in the future as it was in the past,” Wallace said. “Being a real estate company will mean being a science investor. That is a massive mental leap.”

We’re talking just as Fifth Wall announces Ivanhoe Cambridge as its debut investor in the Climate Tech fund.

Wallace: This really represents the first time a large institutional allocator says, “We’re going to put our money where our mouth is and we are going to commit to the science of decarbonizing our industry. And we are going to recognize that to do that requires us to do something different from what we’ve done in the past.” Not buy carbon offsets, not deploy technology that already exists, not talk about it on Bloomberg. Actually invest.

You make this distinction between boring technology, or tech that’s out there that just needs to be scaled across real estate, and tech with “science risk,” that is yet to be developed and will really move the needle.

Smithies: The industry thinks what they are doing is investing in climate tech when they’re going and installing solar panels on their buildings. And it’s not to say they shouldn’t be doing that, but you have to draw a distinction between implementing existing technologies and investing in the new technologies that are required to solve the other half of the climate problem. Today, if you took all the best technology on the planet, the best solar panels, the highest efficiency HVAC motors, and installed them across all of your buildings, you’d only solve about 44 percent of the total carbon problem for the industry. When we talk about actually investing in R&D, we have to start investing in the new technologies.

Wallace: The first thing is actually getting real estate owners to see. They’re like, “Oh, we’re investing in climate tech. We just did a massive green bond issuance and deployed solar on our roofs.” No, no, no, that’s not investing — that’s buying other people’s products. When I buy a carton of milk, I’m not investing in the milk company. The first step is to get them to see that. The second part is a big logical leap for real estate companies: They have this reflexive response of “Why would I invest in science R&D? I buy buildings.” And so part of it is painting the picture that “yes, this is what you historically have done, but you now have a full, new problem, an existential one. Regulators are coming after you and they are going to tax you. Tenants are not going to lease from you. Capital markets are not going to lend to you or insure you. And you might be underwater because you can’t move your buildings.”

There seem to be two types of problems. Pocketbook ones — I can cut your HVAC costs by 5 percent, your OpEx [operating expenditures] by 12 percent — operators seem to get. Existential ones — your building will be underwater — always feel like tomorrow’s problems.

Smithies: The capital markets are forward-looking. They price things according to how much risk they’re starting to see. We’re starting to get to a point where your real estate CFO doesn’t have to be that creative in thinking, “Oh, could this building be underwater?” because the capital markets are starting to price that into the cost of capital. An analogy to this is what we’re seeing in the oil and gas industry, where there’s this concept of “stranded assets.”

In the most extreme case, a stranded asset would be a building or an oil plant that is underwater or on fire because of climate change. But there’s a more subtle form of stranded assets, which is when you can no longer finance them because the public markets will not lend to them. With real estate, too, you’re going to see the public markets tell [operators], “I’m just going to price your risk very differently,” and you’re going to end up with stranded assets if you don’t start thinking about this stuff pretty rapidly.

The Gulf of Mexico BP oil spill is seared into my brain. That incident transformed how all energy companies have to do business. Nothing in real estate can give you that same visceral need for change, either financially or emotionally.

Wallace: That’s the challenge – it’s non-intuitive to most people that the real estate industry is the single largest culprit when it comes to climate change. It’s just hiding in plain sight. The U.S. economy happens indoors, so it should be no surprise that the most CO2 emissions are coming out of our real estate assets. You hear a lot of, “We should focus on the energy industry. We should focus on mining. We should focus on the automotive industry. We should focus on plastics straws.” The reality is that none of those things is the biggest lever we can turn. The biggest lever we can turn is real estate.

Capital markets Darwinism does work.

What we spend a lot of time thinking about is: How do we make regulators, tenants, real estate owners and capital markets aware that this is the real estate industry’s cross to bear?

Smithies: Most of the world has really looked at the carbon problem from a supply side — oil coming out of the ground, coal coming out of the ground. But it’s only in the last couple of years that people have started thinking about the demand side of the problem. That’s when you say, okay, transportation is this much, industrial processes are this much, buildings are this much. It’s more of a flip in how we’ve already done the accounting, but it’s always been true.

There is that realization at the consumer level — I am now more mindful of how I go about my day. But I guess it almost makes no difference if the real estate industry doesn’t really get its act together.

Wallace: There is a way you can make a difference. It’s just a little bit non-intuitive. When you’re leasing space, when you’re buying a house, the questions you can ask make a way bigger difference in mitigating the climate crisis than the car you buy or the plastics you do not use. The real estate industry, candidly, has known this for a while. They see their energy bills. They know where the energy is coming from. They know where it ends up. It’s so obvious that it’s hard to see, like the blind spot in front of your face.

Different cities have different levels of climate change wokeness. An owner might think, “I should probably do something in New York because I’m going to get dinged severely by the emissions cap.” How do you convey they need to do that worldwide?

Smithies: It actually turns out that, if anything, America’s behind and Europe is far ahead. That’s very clear. But then in Asia, we’ve seen the sleeping tigers. When they wake up, they move very quickly. Vietnam is going to have one of the world’s largest rollouts of clean energy, India is going to be a renewable energy powerhouse and they’re phasing out a lot of the use of coal. We might have thought that the “third world” wasn’t going to have the money to do this stuff. But it’s actually very similar to how we saw the rollout of cell phones back in the late nineties and 2000s. They leapfrogged a whole generation.

Clean-energy initiatives can be political gambits. Is there enough of a regulatory whip to back them up?

Smithies: You need the threat of regulations. You don’t necessarily need the regulations to be impactful because at the same time, you’ve also got that carrot of the OpEx side of building efficiency. I love to talk about this concept of a climate Trojan horse, these technologies that your CFO wants to install even if they care nothing about the environment. And we’re just seeing more and more technologies fall into those buckets, where you can be willfully ignorant to climate change.

You want to take altruism out of the equation as much as you can.

Smithies: If you look to how Elon [Musk] built Tesla, his number one insight was, “it doesn’t matter how much climate impact one of your products has if you can’t go and sell 100 million of them.” You actually have to have a product that the world wants to buy for impact to be scaled.

Wallace: If the real estate industry does not figure out how to start moving billions of dollars into the science of decarbonizing itself, regulators will. So it’s a question of which path does it want to go down. And that actually connects with what the opportunity is: The real estate industry is about to become the single biggest consumer of climate tech. It is going to create billions, probably trillions of dollars of enterprise value in climate tech. It’s not just culpability, it’s opportunity.

Read more from The REInterview

Looking beyond the public giants, real estate is such a dynastic business that owners are almost programmed to think long-term. So I’m surprised there hasn’t been much from the leading industry families in New York and California on this.

Wallace: I can tell you where those CEOs and where those real estate companies are going because capital markets Darwinism does work. They are on the wrong side of history and it will end poorly for them. Some real estate companies will get this and will transform themselves and will start to look something not quite like what we historically thought of as a real estate company, but a little more like a real estate company meets R&D lab for climate tech meets energy company. And the ones that do will look like Tesla stock, versus all the other automobile manufacturers.

I love to talk about this concept of a climate Trojan horse, these technologies that your CFO wants to install even if they care nothing about the environment.

Smithies: Look at oil and gas, where you have Ørsted, a Danish oil major [multinational firm]. They flipped on a dime and said, “We are going to become a 100% renewable energy company.” They’re now the world’s largest offshore wind owner and operator, and their stock in the last two years is up 300 percent whilst all the rest of the oil majors are down on average 20 or 30 percent.

Pretty much every building worth its salt in New York is LEED Gold, LEED Silver, something. But is that making a dent in any way, besides a nice logo for a landlord’s website?

Smithies: It’s a drop in the ocean of what we actually need to be doing. I don’t want to discourage people from trying because it’s a first step, but assuming that it is the only requisite step you need to do is a bald-faced lie that I think the industry has been telling themselves.

Wallace: The fundamental hard problems of getting real estate assets to true carbon-zero are in front of us, not behind us. It’s not a question of adopting what we have today. It is yet to be created. And no one’s talking about this gigantic R&D science hole. The gap is billions of dollars that [needs to go] into science R&D. (Fifth Wall estimates that real estate companies have invested just under $95 million in climate tech.)

Real estate is a business of certainty. You look at a pile of dirt and…

Wallace: Used to be a business of certainty.

Fair. But you could pencil things out: Here’s what I’m paying for the land, here are my soft costs, hard costs, here’s what I can make. What you’re talking about though is a leap of faith.

Wallace: It can be seen as scary, but it’s actually an opportunity for real estate companies that embrace this. They have this power of incumbency. They can recharacterize and reinvent their business and start investing in the tech to change what it is they do.

Smithies: Let’s say we are putting money into companies that are inventing the new technologies that are required to build carbon-zero buildings. We happen to invest in this company, let’s call it “Building to Zero Inc.” It has invented the only way to build a high-rise that is net-zero. Our LPs, by virtue of the fact that they are invested in the funds, are the only commercial real estate folks who get access to this technology. Now they are the only people in the world who can build net-zero high-rises. They get the best tenants into those buildings. They get the best cost of capital on those buildings. All of a sudden, if you happen to just be invested in this company at the right point in time, you are that real estate owner whose stock is going through the roof. And everybody else who doesn’t have access is relegated to Class B stock.

Wallace: You have to run to stay in the same place. It’s like the Red Queen from Alice in Wonderland.

Alice and the Red Queen (iStock)

During the Space Race, there were so many technologies created that today have broad, cross-industry applications. Do you think climate tech for the built word has that potential?

Smithies: It’s inevitable. There are always these fantastic spillover effects. The number of opportunities that people are going to bump into is mind-boggling.

I have a Jeep Wrangler that’s a gas-guzzling disgrace, but I love it. I would be willing to pay a monthly tax to continue driving it, but only if there were a way to measure my activity — not some generic standard. Extend that analogy to buildings. Would that do the trick?

Smithies: The fact of the matter is that unfortunately, offsetting is not going to get us out of this problem. We actually do need to start cutting CO2 out of the underlying operating businesses and the buildings.

Wallace: And the media gets that now, too. We saw this with Brookfield. (The company, which is not a Fifth Wall LP, is looking to raise a $7.5 billion Climate Tech fund.)

[Vice chairman Mark Carney] of Brookfield says, “We’re net-zero.” What he actually meant is that they had done something called “aggregate avoided emissions,” which is basically the equivalent of saying, “I lost weight because I didn’t gain weight.” It’s a ridiculous construct. (Carney later walked back those remarks.)

The regulations right now, such as Local Law 97 in New York, use size [buildings over 25,000 square feet are subject to the emission caps]. Arbitrary benchmarks like that are subject to being gamed and being legally disputed. Is there a more bespoke metric out there that would be fairer and more transparent?

Smithies: This is one of the most interesting places to actually invest as a venture fund. There are going to be a bunch of data-science and analytics companies [for real estate]. It’s early days, but I don’t think I would be being bombastic if I said I see one of these companies every week.

In oil & gas, there’s a company called Kayross that is going down to an asset level: How much energy is coming out of the ground from a particular well? The manufacturing and supply chain industry is probably next. And then the next big shoe to drop is going to be building materials.

Your thesis at Fifth Wall seems to be: Bet on the best startups and then play kingmaker for them by presenting them to your owner-operator LPs who are their biggest clients, as well as to other startups in your portfolio with whom they can create a powerful suite of services. Is there potential to replicate that with Climate Tech?

Wallace: It’s the same playbook. But I want to paint the other side of the picture, using our proptech fund and Lennar, the largest homebuilder in the U.S. (and a Fifth Wall investor) as an example. They announced in their most recent earnings call that they had returned $1.5 billion to their balance sheet from our investments. That’s a real number for any company. And two, they’re spinning out these noncore businesses and doing things around technology. In so doing, they recharacterized what they were, to Wall Street, to themselves internally and culturally: They’re a platform.

You now have an existential problem. Regulators are coming after you and they are going to tax you. Tenants are not going to lease from you. Capital markets are not going to lend to you. And you might be underwater.

The biggest opportunity for real estate companies is to change and recharacterize who they are and what they do. This is the conversation we’ve been having. What a real estate company will mean in 2030 is so fundamentally different from what it is today. You are no longer an amalgam of assets that’s valued as a bunch of NOIs all thrown together. Real estate companies are platforms, and platforms create opportunities to do things like what Lennar did, like investing in climate tech, like decarbonizing really aggressively and transforming your business.

Greg, you’re coming at this from an outsider perspective [Smithies was at BMW iVentures and Elon Musk’s The Boring Company]. I’m curious how you approach the conversations with these real estate figures.

Smithies: The most pragmatic thing to do is to talk in terms that the industry understands. Building owners and operators and investors understand cost of capital. They understand depreciation on assets. And if we can couch this in those terms — capital and operating expenditures, cost of insurance— that is very persuasive to a lot of people. That is a way to get into the hearts and minds of the fat middle of the industry.

And then the way Brendan talks about it, which is the ethical imperative and the opportunity to remake your business and be the Tesla of real estate, that is going to get your bleeding-edge people.

There doesn’t seem to be any discussion of real estate’s role in climate change at the grown-ups’ table, at say Davos or the U.N. Rob Speyer controls tens of millions of square feet of space globally. Why isn’t a Rob Speyer at the table when these conversations are happening about the future of the world and how we’re going to save it?

Smithies: Some people may have missed this, but in Biden’s campaign, operational efficiency in buildings was near the top of his list of things that he campaigned on. And you could argue that the climate leg of the stool was one of the strongest ones that got him elected.

This is a very large item they want to focus on. Because for every $1 million you invest in clean energy, it creates about four jobs. Whereas for every $1 million you invest in building efficiency, it creates 14 to 16 jobs.

Most global economies right now are trying to do two things. They’re trying to pull their economies out of a nosedive and create jobs, and they’re trying to greenify. Building operational efficiency is on pretty much everybody’s list. So I think it’s a fantastic question: Why isn’t a Rob Speyer at the table? Because government [sure] wants him to be.

Wallace: I had a conversation with Senator [Sheldon] Whitehouse (D-Rhode Island) and asked him a similar question. And he said the fossil-fuel industry is out for blood — how they show up in government is ready for war. And it’s not that the real estate industry isn’t committed to it. It’s just not ready for war. So they kind of receded into the background. But I actually think, and this is maybe the optimist in me, I think it creates an opportunity.

I don’t want the fact that the real estate industry hasn’t done anything historically to be a long-term indictment of it, because we can’t reinvent the past. All we have is the future, and the future of the world depends on us.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

(Write to Hiten Samtani at hs@therealdeal.com To check out more of The REInterview, a series of his in-depth conversations with real estate leaders and newsmakers, click here.)