Taylor Allen said her life after college was a “little bit nomadic,” as she moved from Virginia to China to Washington, D.C., to Florida.

But in March 2019, the now 26-year-old Atlanta native settled in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a city with a population of about 400,000. She’s one of more than 500 recruits who relocated to the city through Tulsa Remote, a program that aims to lure remote workers by offering $10,000 in cash, along with other perks.

“It’s not crowded or congested. It’s quiet, and it’s at a slower pace of living. And I think that’s really nice to have when everything else seems to be on fire in the world,” said Allen, who last year took a job with Tulsa Remote after a previous full-time remote gig was scrapped by her employer. “There’s this ecosystem that supports remote workers. You don’t feel alone, you don’t feel isolated.”

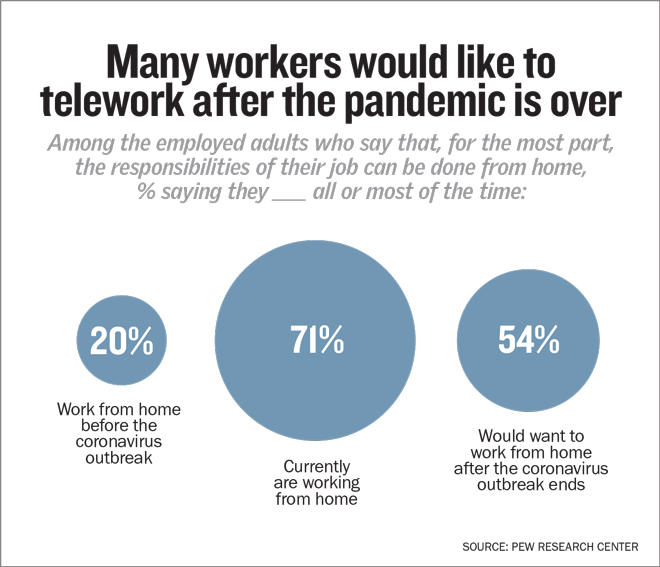

Nearly a year into the pandemic, many employees whose companies instituted work-from-home policies still haven’t returned to the office. According to a recent Pew Research Center survey, more than half of those who can work from home would choose to do so after the pandemic ends.

And some of those workers are leaving behind the pricier urban cores — cities like San Francisco or New York — in favor of communities with more space at a lower price.

“For the first time, they’re free to live wherever they want,” said Evan Hock, co-founder of MakeMyMove, a digital platform that connects telecommuters with communities offering relocation incentives. “We’re finding folks moving because they want to be closer to family. They want to be closer to the water or the mountains. Some of them are just moving to get a more livable lifestyle. The reasons vary, but we think the trend will persist.”

Pay to stay

Pay to stay

Tulsa Remote launched in November 2018 with the goal of attracting full-time remote or self-employed workers to Oklahoma’s second-largest city. In its first year, it received more than 10,000 applications, and the number more than doubled in 2020. As of early February, 8,500 people have applied, making it possible that the 2021 total may reach 100,000, Allen said.

Other cities have launched similar initiatives that offer cash incentives for relocating remote workers.

For the past three decades, the Shoals Economic Development Authority in Alabama focused on recruiting companies to the region, which consists of four cities in the state’s northwestern corner.

But several years ago, officials realized that those firms didn’t necessarily have many employees working full-time in offices.

“We thought, ‘Well, what if we just target the people individually?’” said Mackenzie Cottles, who’s on the authority’s marketing team.

The authority launched Remote Shoals in 2019 and recruited 10 workers from cities like San Francisco, Seattle and Nashville. The initiative awards $10,000 to each selected recruit whose annual income is $52,000 and up. And while it originally targeted tech workers, it’s since opened up to all industries.

In its first year, the program had 200 applicants, but that number shot up after the pandemic: In December alone, it received 100 applications. The program will fill 25 slots for its second year.

Meanwhile, the Greater Topeka Partnership, a consortium of local economic development organizations based in and around Topeka, Kansas, launched Choose Topeka in September, offering up to $10,000 as an incentive for 15 people who move to the area. Five have already moved in, and the rest of the candidates are going through different stages of the process.

The program launched in January 2020 to assist local businesses with talent recruitment from outside of the region. But in response to the pandemic, it also opened up spots for remote workers, said Barbara Stapleton, who runs talent initiatives at the partnership.

The program awards the full $10,000 to candidates who earn $60,000 and up and buy homes in the community. The award is reduced to $5,000 if they rent. If their paychecks are smaller than $60,000, the award amount is reduced accordingly, Stapleton said.

That sort of homebuying incentive could help energize the local real estate market, said Amanda Lewis, who owns brokerage Coldwell Banker American Home.

“I think all of that is going to stimulate housing more than it already has,” she said. “And with the prices that we have in our market, it’s very affordable for people to move from the bigger urban areas.”

According to the Zillow Home Value Index, a typical single-family home in Topeka was valued at $141,153 as of December, compared to $512,941 in New York City and $1.18 million in San Francisco.

But these programs aren’t always popular with longtime residents of the communities. Last year, the Northwest Arkansas Council, a nonprofit backed by corporations like Walmart and Tyson Foods, began offering out-of-state remote workers $10,000 along with a gift certificate to buy a new bicycle or to pay for a membership for a local art and cultural organization. But the program has been criticized by locals who believe the money should be spent to improve the lives of existing residents.

And about a year ago, a Redditor said that Tulsa Remote “rubs me the wrong way” because it sends a signal that “we don’t like native Oklahomans; we only want coastal elites moving here.”

Allen said the program’s intention is to recruit people who are excited to contribute to and engage with the Tulsa community. “We have a diverse group with members who have relocated from almost all 50 states,” she said.

Putting down roots

Some programs tie their awards to remote workers’ economic contributions to their new homes.

In Harmony, Minnesota, a town of about 1,000 people in the southeastern corner of the state, up to $12,000 is given to those who relocate and build new homes. That money isn’t a reward but rather a “cash rebate” for property taxes to be paid in the next five years. It’s often used to finish the interior of the house or to buy furniture, directly benefiting the local economy, said Chris Giesen, coordinator of the Harmony Economic Development Authority.

The rebate amount is tiered based on the taxable value of the house. If the house is assessed at $255,000 or more, the owner will receive $12,000. If the house is assessed at $125,000, the owner will receive $5,000.

The agency launched the program about seven years ago to spur new home construction. It’s since resulted in 13 units of new housing, and Giesen said that interest has picked up since the pandemic began.

In Curtis, Nebraska, land is the incentive: For the past 17 years, the city and Consolidated Telephone Company, a telecommunications company in the central region of the state, have been giving away residential lots for people who build homes on them within a specified time period. Though the program doesn’t require its beneficiaries to be out-of-state residents, it has attracted urbanites who work remotely, according to city administrator Doug Schultz. Since the pandemic hit, more calls are coming from residents of cities like Detroit, Chicago, Denver and Portland, Oregon.

Selling a lifestyle

While cash and real estate may draw people to new cities, quality of life is what will keep them there for the long-term.

“A program that’s able to foster community and cultivates spaces where people feel seen, they feel heard, they feel supported, is what’s going to make a program really successful,” Allen, of Tulsa Remote, said. “At the end of the day, we all just want that human connection. We want to know that we’re not alone.”

According to the 2020 State of Remote Work report by social media management company Buffer and startup investing platform AngelList, about 20 percent of remote workers said they struggle with loneliness — a problem that has been exacerbated by the pandemic.

That’s something that co-living company Common hopes to address. The firm — which now manages around 3,500 residential units across the country and raised $50 million in a Series D funding round in September — saw the shift toward working remotely becoming permanent, rather than a temporary response to the health crisis. It then invited proposals from midsize cities to create new remote work hubs, which would combine a modest level of density and perks with a more affordable cost of living.

“Obviously, remote workers aren’t a monolithic group. Different workers are looking for different things,” said Brad Hargreaves, Common’s CEO. “But we did believe that affordability was the key characteristic in the remote work hubs. One of the reasons why many workers might be leaving a place like San Francisco or New York is because of high housing costs in those cities.”

In addition to affordability, selection criteria included a city’s appeal to remote workers, as well its ability to absorb at least 150 residential units and the degree of support from local communities.

“We didn’t want the remote workers to be a spaceship dropped into some unsuspecting city,” Hargreaves said. “We wanted [the hub] to kind of grow from the fabric of that city itself.”

The company received 28 proposals and, in late January, selected finalists in New Orleans; Bentonville, Arkansas; Rocky Mount, North Carolina; Ogden, Utah; and Rochester, New York. Common will partner with these finalists to work on the design and the marketing of the development.

Outlier Realty Capital, a real estate investment firm based in Bethesda, Maryland, is behind the Utah proposal, which would build hubs with housing, office space and retail on two parcels in downtown Ogden.

Peter Stuart, Outlier’s managing partner, said the firm is hoping to attract a diverse group of residents to its hub. “Young families with kids to singles, young working professionals — we want to be as inclusive and diverse of a community as possible,” he said.

The development includes another parcel in the Powder Mountain ski resort in Eden, about a 30-minute drive from Ogden, in partnership with the resort’s owners. Details have yet to be finalized, but the idea is to allow remote workers based in the urban hub to spend a week or a weekend in the Powder Mountain hub to enjoy outdoor activities, Stuart said.

In North Carolina, meanwhile, the 150-acre Rocky Mount Mills development is poised to grow in partnership with Common. The former cotton mill has already been partially converted into a live-work-play community with about 110 residential units, traditional and flex offices, five restaurants, seven breweries, a coffee shop and outdoor space. The campus remains popular even amid the pandemic, with a waitlist for its residential units.

A new remote work hub would add to the lifestyle options that Rocky Mount can offer, according to Evan Covington Chavez, the complex’s development manager.

“This idea of having a quality of life component is becoming more and more important for companies big and small, and for regions in terms of recruitment,” she said.