Eric Yip came tantalizingly close to the jackpot on a bet that struggling malls would suffer sweeping losses. Then he got wiped out by “the widowmaker.”

Half a decade ago, Yip’s hedge fund, Alder Hill Management, was one of the leading players shorting CMBX, the commercial mortgage market’s answer to the S&P 500. Malls did perish, but their death took longer than Yip had accounted for, and in 2019, after more than two and a half years bleeding capital, he acknowledged defeat and shut the fund down.

Had he been able to hold out just a little longer, Alder Hill would’ve still been in the game when Covid hit and Yip’s bearish trade would have reaped riches.

“He was in it too early and didn’t have the staying power to survive,” said John Devaney of United Capital Markets, a CMBX market maker. “Some of the guys who shorted mall derivatives greatly misunderstood how long it would take.”

Yip fell victim to what Wall Streeters call “the widowmaker” — an esoteric corner of the securitized mortgage market that seduces gamblers with the siren song of the next big short.

Read more

Now, speculators are trying again. Only this time the existential crisis they’re targeting isn’t in malls, but offices. Short sellers are placing billions of dollars’ worth of bets on CMBX on the belief that remote work and $108 billion worth of securitized office loans set to mature in the next five years will wreak havoc on bondholders and the overall market.

It seems like a good bet. Hardly a day goes by without news of an office building in default or lenders who are unable (or unwilling) to refinance debt.

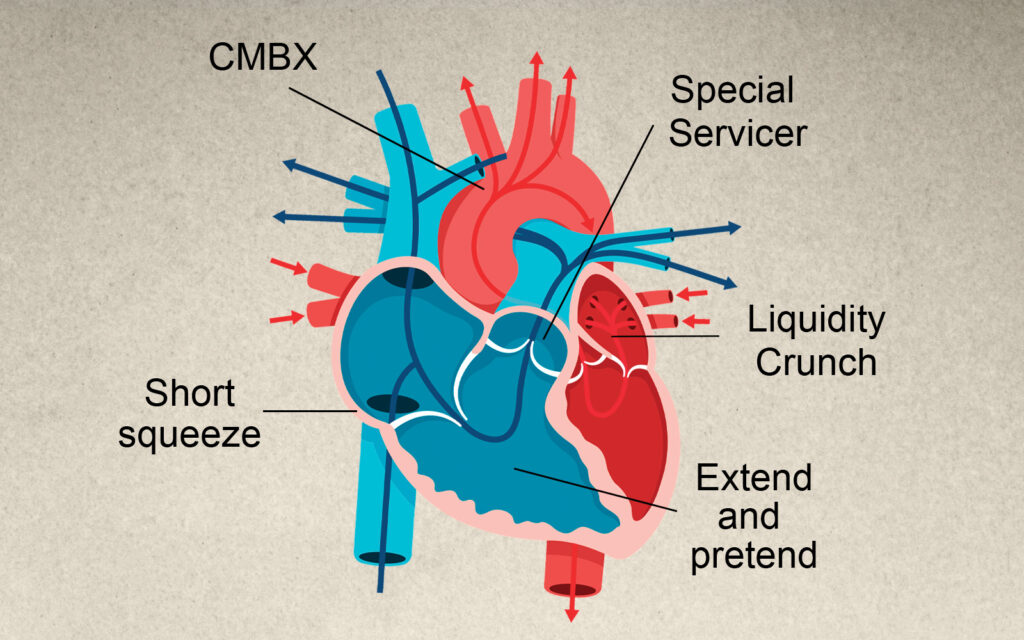

But that’s just the beginning. Nailing the short requires an intimate understanding of how these trades work, according to CMBX veterans. Even the most thoughtfully planned trade can be undone by the various parties — special servicers, bondholders and even outside meddlers — looking out for their own interests.

Real estate’s tendency to extend and pretend its problems for another day can stretch timelines from months to years. And the tricky technical aspects of CMBX can wreck a position long before loan-to-value ratios or maturity dates come into play.

Most of all, the people who’ve seen firsthand why the CMBX short has earned its ghoulish nickname say the secret to success is twofold: get the timing right and then have the fortitude to white knuckle it when the widowmaker acts out.

Out of Office

CMBX is a series of mortgage indices that first came out in 2006. It’s since been one of the main ways speculators can bet big on the real estate debt market.

Each series is made up of 25 CMBS deals representing different types of properties (malls, offices, apartments and more), which are sliced into tranches of debt based on risk. The safest slices, the AAA tranches, are used mostly for mundane risk management.

But the riskier pieces, most likely to be impaired when a borrower defaults, are the realms of the gamblers. The BBB- tranche, rated just above junk, is what’s known as the widowmaker.

You’d need the entirety of commercial real estate to fall by 25 percent in valuation. That feels like a lot.

That’s where the cowboys like Yip and billionaire corporate raider Carl Icahn were playing years ago when they shorted the mall-heavy sixth series of CMBX, a bet that became known as “the Big Short 2.0.” The index has since shifted, and the seven series that have come out since 2017 have been weighted heavily toward office loans.

Investors began increasingly piling their bets on those series soon after Covid hit. The net value of bets on the BBB- pieces of those office series peaked at $5.6 billion in February of last year, according to figures from the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation, a financial services company. That’s compared to $9.6 billion at the height of the mall short in March 2020.

Those on the short side of CMBX are betting that offices will default. They include Bruce Richards’ $22 billion investment firm Marathon Asset Management and Dan McNamara of Polpo Capital, who became something of a CMBX celebrity for his very public mall short in 2018.

“I think there’s going to be massive amounts of stress,” McNamara said, adding that he predicted a wave of office distress long before Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank went under in March. “The wildcard we didn’t predict was the regional banking crisis, but it’s just been like a triple whammy — the perfect storm for CRE markets.”

With their bets placed, those investors are sitting back and waiting to see what happens. Those reading the headlines today and thinking about jumping in are probably too late.

Prices on some of the office-heavy tranches have dropped to the low-$0.70s on the dollar. When 25 to 30 percent of distress is already baked into the price, it would take extremely deep pain in not just offices but all CMBX deals in the index to make a trade profitable.

“You’d need the entirety of commercial real estate to fall by 25 percent in valuation. That feels like a lot,” said Rich Hill of real estate asset manager Cohen & Steers. “CMBX is not necessarily a great short if you’re just focused on office loans.”

Timing is everything. Show up too early and you risk running out of capital. Too late, and you need an apocalypse to get paid.

Send bachelors and come heavily armed

Yip’s Alder Hill became a cautionary tale of CMBX, but it was far from its only victim.

Sorin Capital Management, a Stamford-based hedge fund run by Jim Higgins that shorted CMBX.6, eventually had to pull out and return money to investors in 2019. Anchorage Capital Group, one of the biggest hedge-fund investors in distressed debt, had a position in CMBX that it closed in 2021.

As buzz around the big office short became louder in March, Morgan Stanley trader Kamil Sadik issued a warning.

“Shorting CMBX BBB- is regarded as the widowmaker — the undoing of many a young trader’s career,” Sadik wrote, adding that betting against the index while it had already underperformed similar shorts on high-yield debt “was viewed as psychotic.”

Here’s how it works: An investor who wants to short a CMBX index enters into a credit default swap with someone on the other side, who wants to go long. It’s similar to an insurance policy. The short investor pays a premium each month for the insurance, and the other side compensates them if a borrower in the pool falls short on interest payments or can’t repay their loan.

This is one of the main risks of shorting through credit default swaps: It can take a very long time for those payment events to happen. The resolution time for special servicers averaged around 23 months last year. If you’re waiting around months or years for these properties to fail, those premiums add up.

“If you’re short, time is your enemy because you’re paying these premiums year after year and the losses have to be very big to offset your carrying costs,” said Trepp’s Manus Clancy. “I think the biggest issue for shorts over the last three years has been a willingness for owners of properties to fight for them.”

In extreme cases, those fights can drag on forever. One CMBX contract has been outstanding for nearly two decades. It’s from the first series that came out in 2006 and includes a zombie loan on a Denver shopping center that was foreclosed on but never sold.

There’s reason to believe offices can hang around even longer.

Malls and shopping centers often have co-tenancy clauses that allow smaller tenants to split if an anchor tenant leaves, hastening a property’s failure. Offices don’t have those kinds of agreements, and with staggered 10-year leases, it can take a long time for changes in work patterns to affect property values.

Matthew Weinstein of the investment firm Axonic Capital said the fate of shorts depends on how special servicers decide to work out troubled loans.

“It’s a widowmaker if every office loan gets extended five years,” he said. “If realizations occur and special servicers start taking back assets and selling assets, then it’s definitively not.”

Special interests

One person who’s certainly got opinions on the special servicers is Carl Icahn, who disclosed that as of late 2020, he had made $1.4 billion on his CMBX.6 bet.

If not for a special servicer, it might have been more.

Icahn last summer sued Rialto Capital, alleging the special servicer had dragged its feet on the sale of a foreclosed outlet mall near Las Vegas. Icahn claimed Rialto was pressured to do so by mutual fund manager Putnam Investments, which was on the long side of the mall trade and stood to benefit from any delays in selling.

Icahn’s legal team likened it to an insurance provider pressuring a doctor to declare a sick patient healthy.

As evidence, they included a letter Putnam had sent threatening legal action. But Rialto’s attorneys pointed out that the letter was sent to a different servicer regarding a different trust — saying Icahn was barely concealing his real motive: intimidating the servicer that got in the way of his short.

“What Icahn wants is for declines in value to be realized more quickly,” the servicer’s attorneys wrote.

To sue Rialto, Icahn purchased bonds in the index he’s shorting. It’s an ethically dubious move, comparable to shorting a company’s stock and then gaining a seat on its board to call for the CEO’s ouster. But Icahn’s team said there was no conflict of interest.

“The complaint is very candid and above board about the Icahn fund’s interest in CMBX,” Mike Hanin, Icahn’s attorney at Kasowitz Benson Torres, told TRD. “It’s shedding light on a pattern and practice of servicers like Rialto that sit on these properties for their own benefit in a manner that is contradictory to the interest of all bondholders.”

TKO

Even if you’ve got the real estate fundamentals figured out, the technical intricacies of the widowmaker can get you.

CMBX is what’s known as a synthetic index, meaning that it’s designed to replicate the performance (or nonperformance, in this case) of CMBS loans — but it’s not actually tied to them.

In theory, the price of CMBX should rise and fall depending on whether borrowers are repaying their mortgages. And most of the time it does. But at certain points pricing tends to diverge, and this is when it can be the most unpredictable.

“The index kind of has a life of its own,” said Constantine Korologos, a structured finance professor at NYU.

One reason that prices can become disconnected is that CMBX, like other synthetic indices, can be influenced more by the supply and demand for credit default swaps than the bonds it tracks.

The index kind of has a life of its own.

That happened during the big mall short. When mall losses failed to manifest early on, the prices for the default swaps should have fallen. But they were being propped up by Putnam and asset manager AllianceBernstein, which were pushing around the market based on the huge positions they’d built up on the long side of the trade.

That points to another quirk of CMBX — it’s a relatively small market that trades in chunks of a few million dollars at a time. Investors with large positions have serious sway.

It’s also got something of a liquidity issue. One of the benefits of CMBX is that the default swaps are much easier to trade than the underlying bonds. But that liquidity tends to dry up in times of volatility, which can leave investors in the lurch when they need to sell the most.

Nick Godek of S&P Global, which last year merged with the company that administers the index in a $140 billion deal, declined to comment on CMBX’s drawbacks. But he did point to one of its big strengths: It allows investors to focus entirely on credit risk.

Mortgages come with different kinds of risk. One is duration risk: If you hold a fixed-rate mortgage and interest rates go up, your asset is worth less than others that are now yielding a higher return.

The credit default swap isolates that duration risk and focuses solely on a borrower’s ability to repay their loan.

Empty offices, crowded trades

In the heart of downtown Milwaukee, a 36-story office tower stands at 100 East Wisconsin Avenue. The property, long a fixture of the city’s skyline, is now a poster boy for what happens to older, undesired office buildings.

Last month, a judge approved the sale of the property to a residential developer for just shy of $29 million — well less than its $47 million CMBS loan.

Good news for short sellers? Not exactly.

The portion of the loan in CMBX.10 makes up a relatively small piece of the index, and according to Trepp it’s not significant enough to trigger a payment to the hedge funds shorting the BBB- tranche.

That’s a scary reality for anyone shorting the index now. The writing may be visible on the wall for offices. But because these indices are diversified, it’s not clear that shorting CMBX is the best way to cash in on that belief.

Some have suggested moving away from the BBB- tranche and up to the more highly rated pieces of debt where the fear of distress is not yet priced in.

Trepp’s Clancy said he thinks that even if special servicers move quickly to take properties, it will take considerable time to resolve them. Shorting the office space, he said, is no sure thing.

“I don’t think it’ll be like shooting fish in a barrel,” he said, “where shorting office is a clear pathway to making a fortune.”